The Pandemic and the Emerging Markets Crisis: How Fragile are the Economies?

Utku Demir and Merih Uctum

June 11, 2020

The Emerging Market (EM) economies that came out of the 2008 financial crisis relatively faster than advanced economies are hard hit by a quadruple-whammy this time: the pandemic, capital outflows, economic recession, and debt crisis. In March 2020, more than USD100 billion flew out of the EMs.

This analysis looks at the flight to the safety of global investors and its impact on these economies that owe more than $8 trillion in foreign-currency debt.

The EMs have come a long way since the 1990s when they were unable to borrow in their currency, a phenomenon dubbed “the original sin” by Eichengreen and Hausmann, which made them dependent on external financial conditions. Adverse global conditions could lead to capital flight and depreciation of their exchange rate, which pushed their economies into insolvency since the value of the debt burden rose in local currency. If foreign creditors lost confidence in the local economy, they could abruptly reduce the international flow of the capital in the economy. This phenomenon is also often accompanied by domestic residents increasing their investment abroad. Called a “sudden stop,” the abrupt reversal of capital flows would be often accompanied by recession and a currency crisis through a run on EMs currency. During the last several decades, however, following improved economic and financial management and strengthened banking systems, most EMs have been able to borrow in their currencies. Yet, they now face another problem, the “original sin-redux,” as described by Carstens and Shin: since the performance of investors in EMs in local currency is evaluated in USD, a depreciation of the EM currency is costly for investors. So, during an international crisis, this heightened risk leads to capital flight and further depreciation of the currencies.

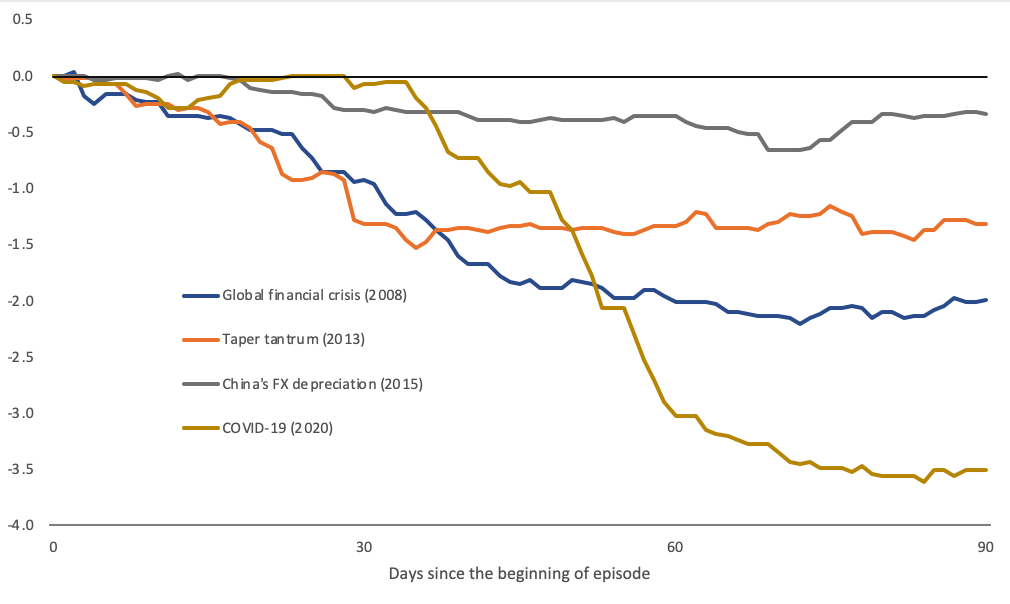

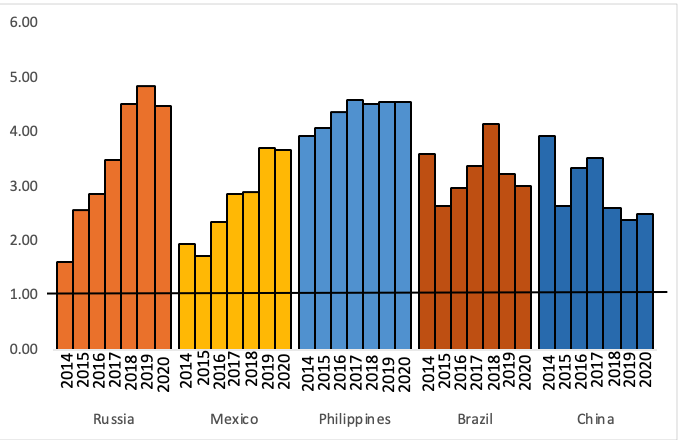

EM economies are no strangers to capital flight. In recent history, several episodes led to capital outflows from these countries. Since the Global Financial crisis, they have been hit by the Taper Tantrum when the Fed decided to stop quantitative easing, which led to a market selloff of EM currencies in a panic; a Renminbi devaluation that reduced its value against the USD for the first time in 20 years and rattled the markets; and the 2018 EM selloff following global trade uncertainties and the strength of the USD. The market panic of this year has been more severe. As the spread of the coronavirus ripped through financial markets and fears of a recession gripped investors, capital flows to EMs collapsed at the onset of the pandemic. Although some of the outflows slowed down and new inflows took place since then, the decline has been much more severe than the financial crisis or any other episode of market disturbance to these economies (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of portfolio outflows episodes (percent of International Investment Position)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2020.

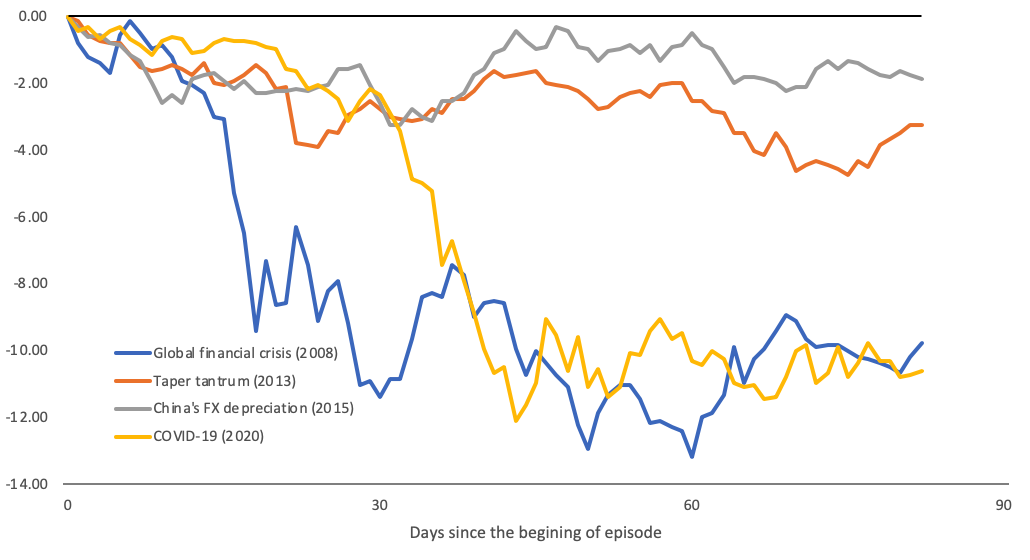

In conjunction with massive capital flight, the value of EM currencies collapsed. Since January 2020, the fall in EM exchange rates due to the pandemic-induced lockdown was compounded by plummeting oil and commodity prices, which adversely affected the exporters. The flight to safety by investors, who piled into the dollar as the virus spread over the continents, exacerbated the free fall of these currencies. Figure 2 depicts the change in the value of EM currencies since the beginning of each episode. In the first 90 days of the pandemic, the decline in the currencies was severe but more abrupt than the decline during the same period of the Great Financial crisis.

Figure 2. Comparison of currency depreciation episodes (bilateral EM rates against the US$)

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data and authors’ calculations. EM economies include China, Mexico, Korea, India, Brazil, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Israel, Indonesia, Philippines, Chile, Colombia, Saudi Arabia, Argentina, and Russia.

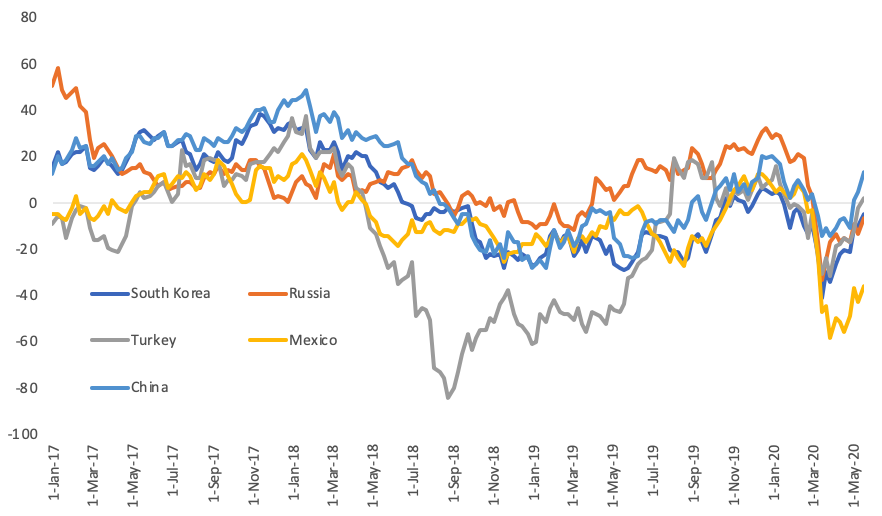

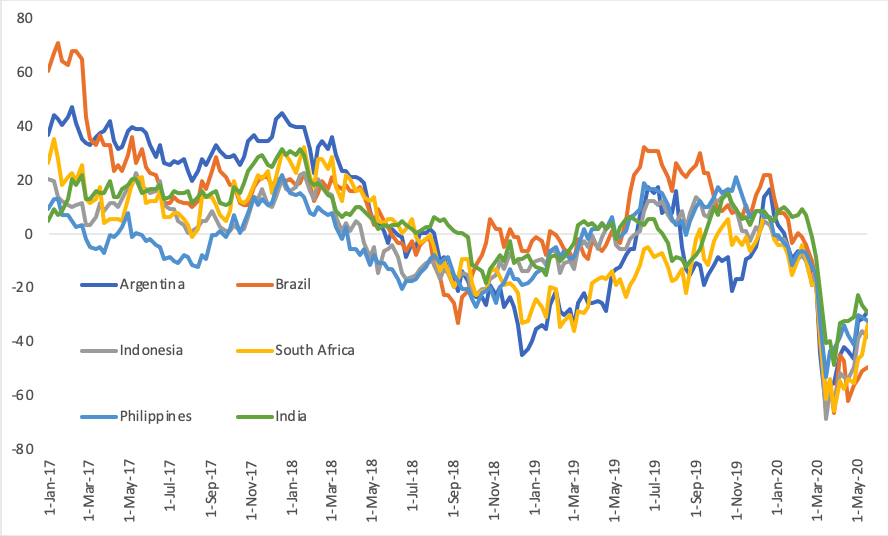

Not all countries have been impacted by capital flight in the same way. To examine this, we can consider variations in exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

An ETF is a type of investment fund that consists of portfolios that track the price and yield of an underlying index. As such, EM ETFs are readily available and can give an understanding of the recent fluctuations in portfolio flows from these economies. Earlier in the year, most EMs, except for the Philippines, have seen sharp declines in net ETF positions, which shows the extent of capital flight from these economies in March (Figure 3). The outflow was abrupt and substantial, paralleling the collapse of their currencies.

Although the net positions subsequently improved, they remain well below the 2018 levels.

Figure 3: Exchange-Traded Funds (year-over-year percent change)

Source: Investing.com, ETF Equities in the United States Market, issuers: iShares for all countries except Argentina. The issuer for Argentina: Global X

As a result of these massive shocks, EM economies are grappling with the fallout from the pandemic, shutdowns, loss of cheap financing, a staggering recession both at home and abroad, and an inability to service their debt to foreign creditors. Despite the G20’s initiative to suspend debt repayment by the poorest countries, it does not cover the debt owed to private creditors. Further, many EM countries are excluded from this deal; several of them are therefore facing a risk of default, as illustrated by Argentina’s May 22 default, its 9th since 2001.

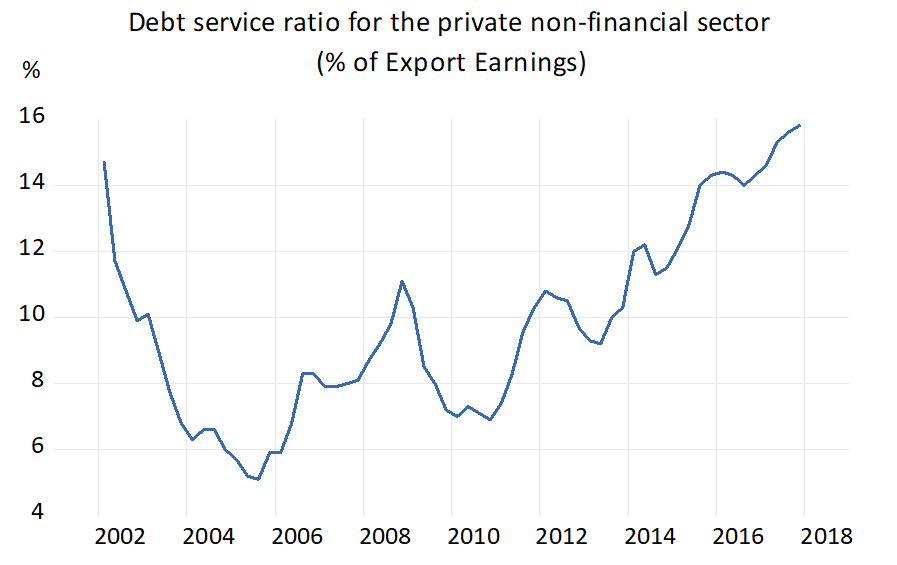

To analyze the severity of default risk, various indicators are used to assess the vulnerability of economies to sudden stops.

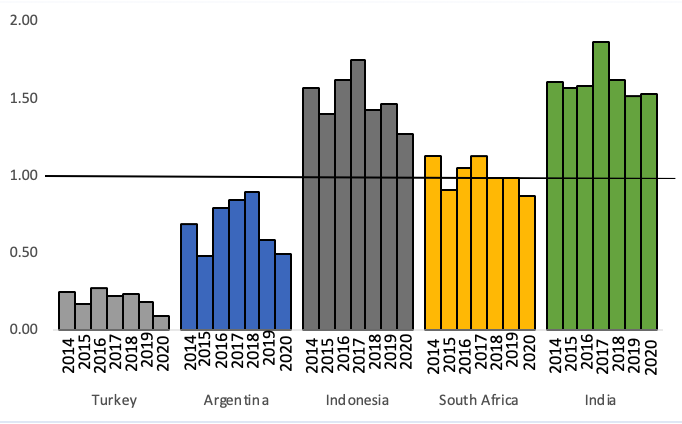

Typical indicators include the level of external debt as a share of exports, the ratio of debt service to international reserves, and the ratio of current account balance to GDP. In this analysis, we will instead use the Guidotti-Greenspan rule, since it compares the country’s international reserves to its short-term external debt with a maturity of one year or less. If the ratio is greater than or equal to 1, then the economy has built sufficient reserves to weather a massive flight of short-term capital for one year (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Guidotti-Greenspan rule of reserve adequacy (Reserves/short-term external debt by remaining maturity)

Source: SP Global Ratings, Sovereign Risk Indicators 2020 Estimates, as of April 24, 2020, and authors’ calculations.

Argentina and, in particular, Turkey stand out as having chronically inadequate international reserves to resist a sudden stop of capital flows. In 2020, South Africa fell into the same category of dangerously low reserves. India and Indonesia are currently in a relatively safe zone. They both have just sufficient reserves to cover a short-term crisis, although Indonesia’s ratio has been declining since 2017. If the EM crisis deepens, both of these economies are likely to suffer from a run on reserves. The other five countries, Brazil, China, Mexico, the Philippines, and Russia, have sufficient reserve adequacy without needing foreign borrowing for at least one year.

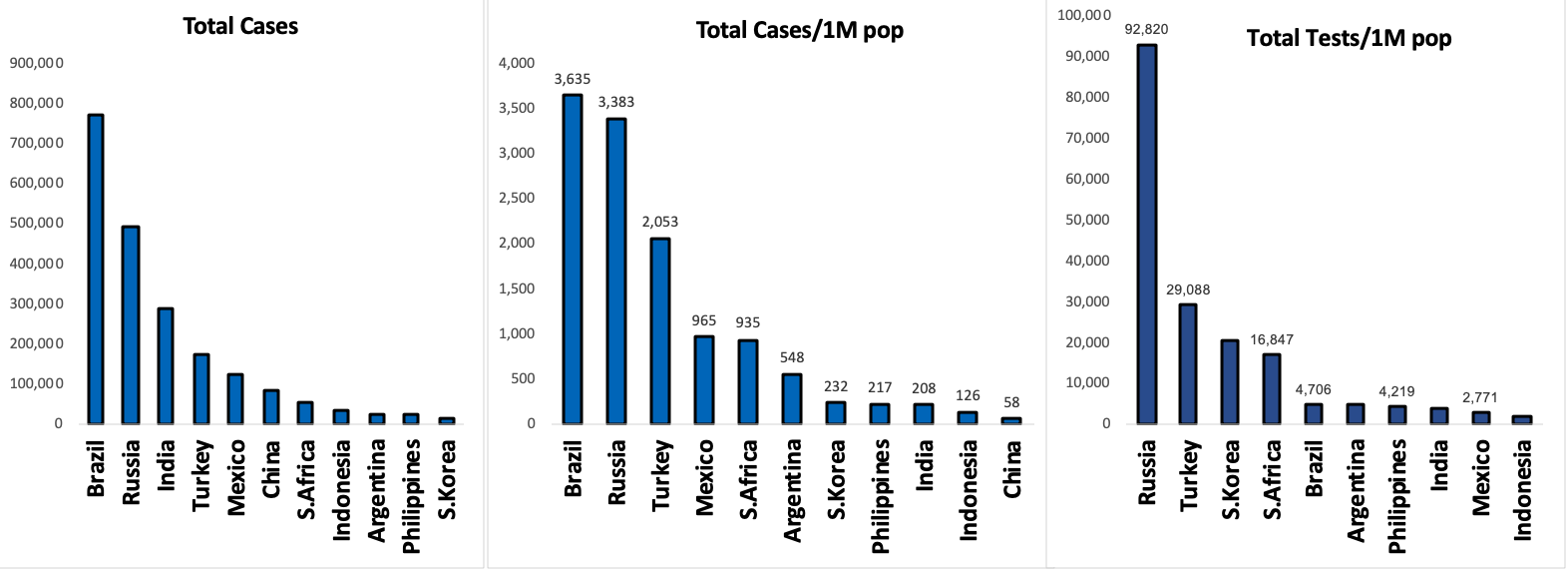

These conclusions should be evaluated against the current health crisis that the economies are facing. If a country’s health system is overwhelmed by infected people who need to be hospitalized, the economy’s opening will only aggravate the crisis and delay recovery. Figure 5 displays total cases, cases per 1 million population, and tests per 1 million population.

Figure 5: Total cases of infection as of June 6/2020

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?utm_campaign=homeAdvegas1?

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?utm_campaign=homeAdvegas1?

Despite Brazil and Russia satisfying the reserve adequacy criterion, they have the world’s second and third highest numbers of cases respectively after the United States and are ranked above all the EM countries in our analysis (first panel). Brazil is holding second place worldwide even after accounting for the population; among the EM countries studied, it has the highest cases per 1 million people (second panel). Some political leaders argue that high numbers only reflect high rates of testing.

If a country has high testing and high number of cases, then this is a valid argument. However, if there are low testing and a high number of cases, then this is not the case–in fact, the actual number of cases is likely to be even higher than the official numbers. In regards to testing, the worst performing countries in our sample are mostly those economies satisfying the reserve adequacy condition: Brazil, the Philippines, India, Mexico, and Indonesia (third panel). Argentina stands out as deficient in both reserve adequacy and testing. With low rates of testing and increasing numbers of infections, India and Indonesia are in danger of facing adverse economic conditions and/or a financial crisis.

EM economies are facing a rare case of twin crises, economic/financial, and pandemic. These potentially amplify each other and therefore need to be addressed simultaneously. Countries that tackle the health crisis as seriously as the economic slowdown are expected to fare better and return to attracting foreign investment in a virtuous cycle. By contrast, countries prioritize solving the economic crisis over protecting people for a rough ride.