Fotios Siokis

October 21, 2019

What are unconventional monetary policies? How are they implemented in the European Union? What does the future look like? In this article we address these questions. On September 12,2019, the President of the European Central Bank (ECB) announced a new monetary stimulus package, prompted by the entrenched low inflation rate and an economic slowdown that has proved to be more protracted than initially expected. The inflation and economic growth prospects in the euroarea, which were both revised downward to 1.2% and 1.1% for this year and 1.0% and 1.2% in 2020 respectively, have taken a heavy toll due to the persistent weakness in manufacturing and extraordinary uncertainty concerning international trading arrangements and geopolitical alignments.

A zero lower bound (ZLB) on the Main Refinancing Operation interest rate (currently at zero and equivalent to the Federal Reserve’s target rate) had eroded the use of traditional monetary tools, prompting the ECB to adopt unconventional measures. These were first introduced in early 2000 by Japan in its battle against deflation and had been previously employed in periods of heightened financial distress amid severe economic downturns, such as the recent Great Recession in the United States and the great sovereign and banking crisis in the euro area. Table 1 outlines these complementary monetary measures.

Table 1: ECB’s monetary policy decisions as of September 12, 2019

| Tools | Action Taken |

| Deposit (overnight facility) rate | Rate decrease to -0.5% from -0.4% |

| Two-tier system | Introduction of two-tier system for reserve remuneration |

| Forward Guidance | Measures will remain at work until projected inflation stabilizes close to but lower than the targeted 2% |

| Quantitative Easing (QE) | Restart asset purchase program at a monthly pace of €20 bn from November 1 until the ECB begins to raise key interest rates. |

| Targeted Longer-term Refinancing Operations (TLTRO) | Lower interest rates for loans while maturity extends from 2 to 3 years |

Source: ECB

Monetary Policy Tools Εxplained

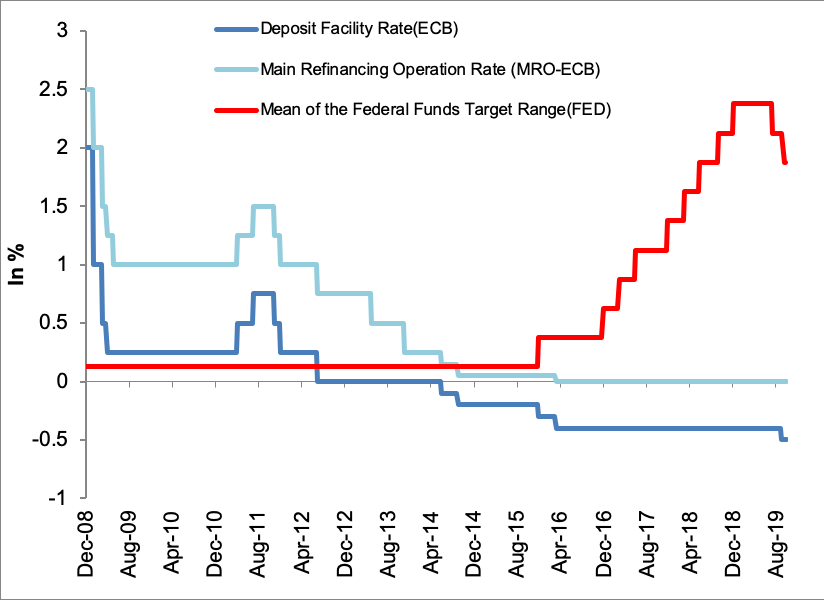

- Deposit (overnight) facility rate. Unlike the Main Refinancing Operation rate that remained at the zero level (figure 1), the deposit rate – the rate that the ECB remunerates for deposits that commercial banks hold at the central bank, in excess of the required reserves – decreased by 10 basis points, from -0.4% to -0.5%.

Figure 1. Deposit rate and the (a)synchronization of the main intervention rates

Sources: ECB and Federal Reserve

The negative deposit rate is a policy measure aiming at decreasing the yield curve at all maturities. It is designed to encourage commercial banks to lend their excess liquidity to households, firms, financial intermediaries, or to invest it in sovereign bonds, rather than to “stash” it in the Central Bank. Although this measure is intended to provide extra liquidity, critics argue that negative rates may adversely affect the profitability of the fragile European banking system. To the extent that a negative overnight rate reduces longer-term interest rates, the income that banks earn from interest bearing financial assets, such as bonds or mortgages, is reduced. Furthermore, the possibility that negative rates may lead to less lending and more risk taking by high-deposit banks cannot be ignored. Neither can the fact that negative rates could be passed on to corporate depositors and savers. For these reasons, the ECB introduced a two-tier system for the banks, under which a portion of reserves, set up to six times the mandatory reserves they hold at the Central Bank, will be exempt from negative rates and earn 0%, while the rest of the reserves will be subject to the -0.5% rate.

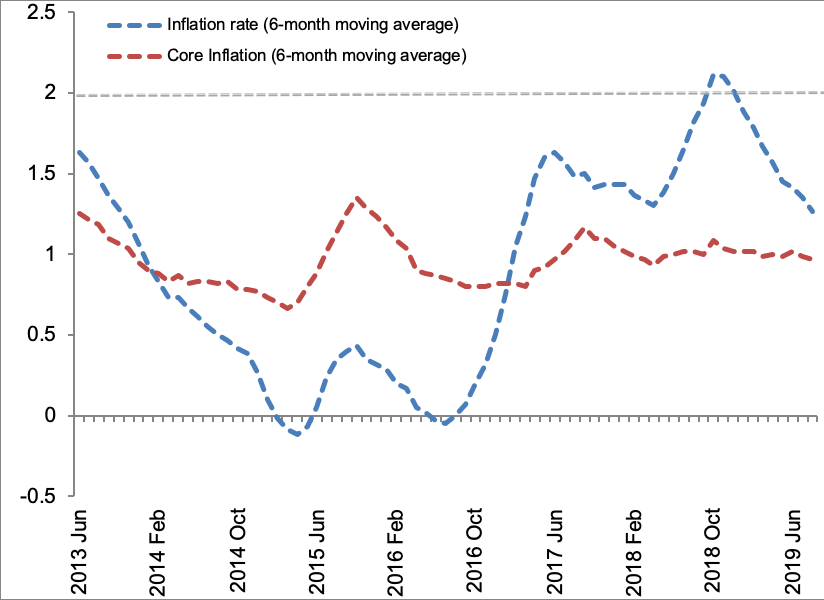

- Forward guidance. Forward guidance occurs when Central Banks communicate with the public about the current state of the economy and the future path of monetary policy. By revealing the path of policy rates, the ECB seeks to influence longer term interest rates and to reduce uncertainty about the mean and variance of asset prices. Central Banks have used two types of forward guidance policy so far: the time- or calendar-dependent guidance and the state-dependent commitment. The ECB’s forward guidance announcement along with the deposit facility rate is state-dependent, conditional on the inflation outlook. The ECB states that as long as the inflation rate remains low and away from the targeted level (close to but less than 2%, as shown in the figure below), the interest rates and the other unconventional monetary policy measures will be accommodative. This is called an “Odyssean guidance” – a form of commitment where the Central Bank pledges to stay on course regarding the interest rate path and other accommodative measures.

Figure 2. Inflation rates in the euro area

Source: ECB

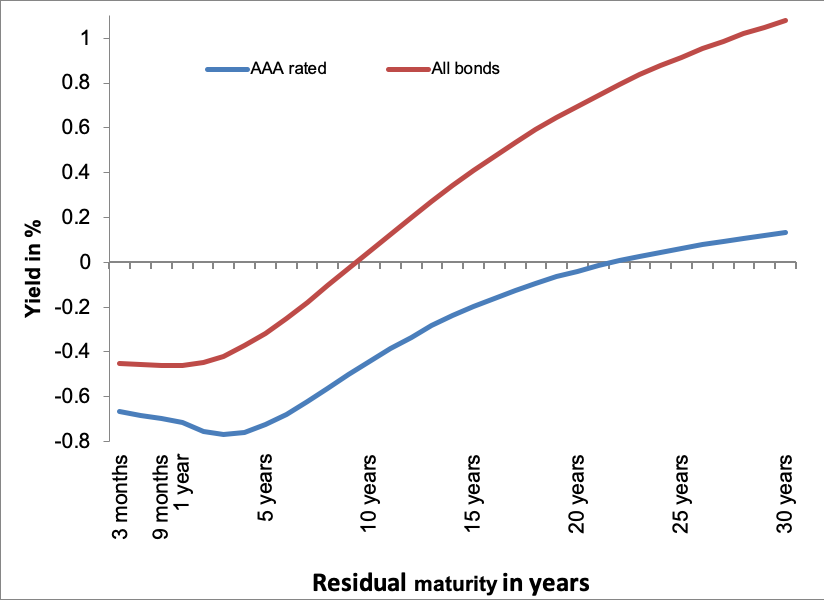

- Quantitative easing (QE). This toolinvolves large-scale purchases of longer-term bonds by the ECB with the aim of easing monetary and financial conditions in order to boost spending. Purchases of government bonds increase their asset prices and consequently lower their respective yields. Asset prices and yields are influenced through two channels, namely the portfolio balance and the signaling channels. The first postulates–given that assets are imperfect substitutes–that purchases of longer-term government assets can also decrease the yields of other assets bearing similar credit risk and duration characteristics. In other words, the sellers of these bonds will seek to rebalance their portfolios by buying other assets that are substitutes for the ones that they have sold. This process will raise the price of other assets (wealth effect) and decrease their yields (lowering borrowing costs for firms and households as well as governments) an action that stimulates spending and investment. The signaling channel operates through the effect on expected future policy rates and can reduce the inflation expectations component (term premia) of long-term interest rates. In this respect, the QE measure is complementary to forward guidance, supporting the ECB’s commitment to stick with the announced accommodative policy. QE seems to have become a key instrument of monetary policy in the euro area which will embark again on asset buying on November 1 at a monthly rate of € 20 billion. Based on the forward guidance rhetoric, QE is intended to last for quite some time and go beyond the €2.6 trillion bond-buying program that was first implemented and lasted through the end of 2018. But such actions are not harmless. QE could distress market conditions by diminishing the supply of long-term bonds in the market, and create a shortage of bonds that institutional investors and others used as collateral.

Figure 3. Yield curve in the euro area as of September 12, 2019

Source: ECB

- Targeted, Longer-Term, Refinancing Operations (TLTRO). TLTROs are monetary policy tools that provide long-term loans to banks. The aim is to provide a favorable bank credit environment, enhancing support for financing the real economy. It will also ensure the smooth functioning of the bank lending channel as the main monetary policy transmission mechanism. According to the new TLTRO, banks can borrow up to 30% of their outstanding loans to businesses and consumers at a rate equal to main refinancing operation rate (0%). In cases where a bank sufficiently improves its lending to the real economy, the interest rate applied could become negative up to the deposit rate (-0.5%).

Discussion

The ECB’s announced measures aim to revive inflation expectations and bring inflation close to its 2 percent target level, something the ECB has fallen short of since 2013 and raised concerns about its credibility. In addition, the new monetary measures can spur economic growth by lowering longer-term borrowing costs for firms and households, and by providing an opportunity for Euro area member states to finance a fiscal expansion with very favorable interest rates.

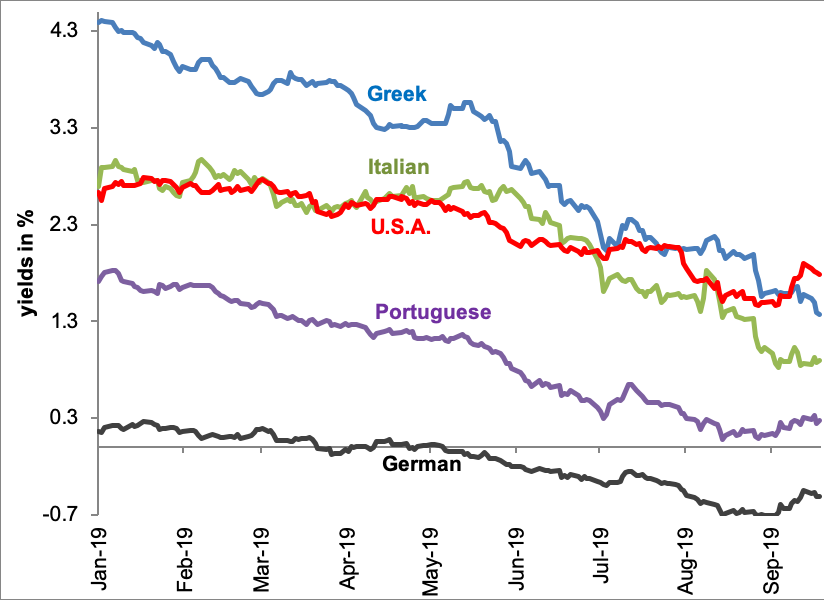

On the adverse side effects of the unconventional measures, this ample liquidity handed to the banking system could easily be simply deposited with the ECB, or invested in higher-risk and higher-yield assets offered. To a certain degree, the downward movement of long-term yields in parts of the euro area, shown in Figure 4, is a testament to “hunt for yield.” By now the Greek 10-year bond yield, a non-investment grade asset is lower than the corresponding AA+ U.S. Treasury. As negative rates narrow banks’ margins, financial institutions could decrease lending and slow the economy. Core banks from Germany, France and Benelux, which account for 85% of excess liquidity, bear the bulk of the cost of these negative rates.

Figure 4. 10-year bond yields of selected countries

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) and Central Banks’ sites

What does the future hold? It is evident that the significant accommodative stance of monetary policy is set for a long time. Although the unconventional measures are mutually reinforcing, monetary policy alone might not be sufficient to revive growth in the euro area. The ECB has willingly passed on the growth baton to the member states, though most have applied austerity measures throughout the crisis and now seem reluctant to conduct a vital, expansionary, fiscal policy.