Greek Debt in Historical Perspective: An Opinion Article

Anthony Rodolakis

November 22, 2017

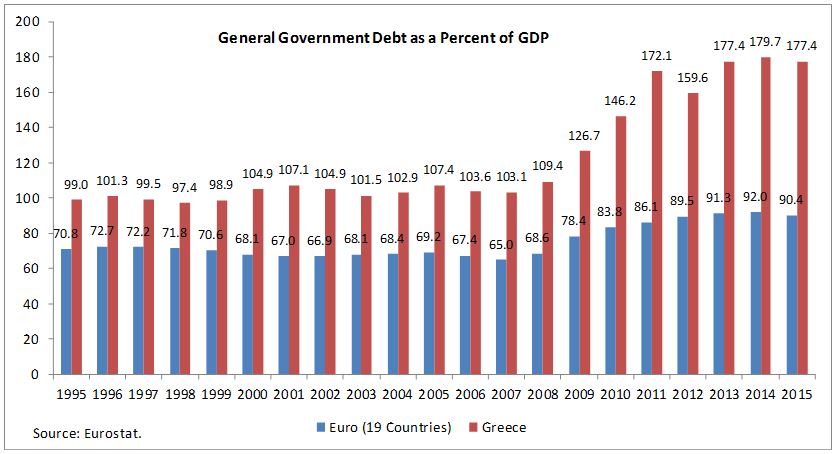

Current fiscal proposals are projected to lead to a sizeable increase in U.S. debt and while people point to the Greek crisis to warn about high debt, a closer look at Greece’s debt history reveals few similarities. Modern Greek economic history is a history of debt. Greece is the country with more years in default to its creditors than any other European nation, being in default in 48 percent of the years since 1826. The 19th Century By the late 1700s Greece’s proximity to Europe and a flourishing trade had allowed the development of a rich merchant class which was able to benefit from the European intellectual enlightenment – and to a large extent precipitate the ground for political independence from the Ottoman Turks. The vast majority of the peasantry, however, had been left in a semi-feudal status and beholden to the local oligarchies for favors. Greece gained independence in 1830, following a turbulent revolutionary war. The debt buildup of that period was largely for loans to finance the war expenditures. The debt burdens the country had accumulated during the war lingered through the 1830s and 1840s and eventually led to a default in 1843. Fifty years were to elapse before the default was terminated.[2] Following the final settlement of the default in 1878, Greece tapped the French capital markets for close to 500,000,000 francs. The terms, however, contained substantial “haircuts,” which was often the case. For example, an 1884 loan of 170,000,000 francs was offered at 68.5 percent, though even then it was undersubscribed with net proceeds of only 100,000,000 francs.[3] In all cases, bondholders were pledged a variety of receipts such as from the state monopolies of petroleum, matches, playing cards, tobacco consumption taxes, and port custom receipts. Nevertheless, both British and French financial experts sent to Greece around this time to examine the stability of finances and the ability to repay the contracted loans on behalf of their banking institutions concluded that bankruptcy was inevitable.[4] The inability to maintain external debt obligations together with the expenses for the program of internal infrastructure development as well as renewed military expenditures led to the 1893 suspension of payments. The 20th Century During the first decade of the 20th century, Greece pursued a strict policy of monetary restraint and fiscal discipline that led to an appreciating drachma. Greece enjoyed rapid growth in certain sectors with the shipping industry exploiting the expanding trade opportunities. The fiscal and monetary self-discipline of those years paid off with net positive capital inflows from abroad. By 1920, the end of the Balkan wars and World War I saw a doubling of the territorial size and population of Greece. Fast forwarding, the end of World War II found Greece and Europe in ruins, but Greece endured another round of fighting. Through 1949 Greece fought a bloody civil war between communists and the National Army that devastated the country, with widespread infrastructure destruction and rapid migration abroad. The Civil War retarded political and economic advances in Greece for several decades, handicapping the country’s economic growth compared to other European nations. The 1950s and 1960s saw rapid rates of growth in the Greek economy premised on large public investments on infrastructure, foreign direct investment, residential investment and a strengthening commercial shipping sector. Despite this growth, “the development during this period is dependent on foreign funding and is asymmetric and unproductive.”[5] In 1950 a Daily Herald correspondent concluded that there are two Greek kingdoms: that of the new-rich of the center of Athens and the aristocratic suburbs and that of the rest of Greece where malnutrition and tuberculosis reigned. With the entry into the European Economic Community in 1981, Greece was able to participate in a community of advanced and wealthy nations. However, the availability of development funds was to prove a double-edged sword. “According to OECD data, between 1981 and 1988, the number of central government public sector employees increased six times more than the active population of the country during the same time period, and public expenditures as a percent of the domestic product skyrocketed from 21 percent in 1976 to 51 percent in 1988.”[6] Overall, between “1975 and 1987, in 13 years, $18.4 billion in loans were contracted, of which $14.8 billion, or 80.6 percent, were allocated for the servicing of existing debt”[7] and not for development. At the end of the decade, the debt/GDP ratio stood at 66 percent. The 1990s saw Greece struggling to implement the conditions required by the European Union (EU) convergence criteria on its path to full monetary union within the Eurozone. Successive Greek governments attempted to contain inflation and largely succeeded, but inflows from EU funds continued alongside the inability to balance the budget. The conservative government of the early 1990s increased debt by 295 percent, which pushed total debt as a share of GDP above 100 percent. Total debt servicing consumed 151.2 percent of regular government receipts as of the end of 1993.[8] With the entry of Greece into the Eurozone in 2001 a new era of optimism and GDP growth had begun, unfortunately, premised on loans at deceptively low-interest rates. In the 2000s Greece was exposed to an international financial environment flooded with liquidity and without any real convergence with the “core” of the EU, continued lack of fiscal discipline, and with already high levels of debt. Greece was allowed to accumulate a debt of over 300 billion Euros that was to allocate the funds to its preferred oligarchic economic cartels that controlled construction projects and other outlets for the contracted loans, as well as allow largesse to the ever-expanding public sector. The 2000s, much like the 1980s and the 1990s, proved a lost decade. The long-promised and much-needed deregulation of cartels across industrial sectors, labor market liberalization, privatization of publicly controlled enterprises, improvement of public administration, restructuring of public and private pension systems, and efficient absorption of EU funds for infrastructure upgrades were delayed or outright ignored by stakeholders. Political leaders avoided any and all direct conflict with their constituencies that tended to be concentrated in the public and private sector unions. In Sum The staggering Greek debt accumulated over the last 20 years is not a unique phenomenon for present-day Greece. Since the 1820s historical, political, demographic, and sociological circumstances have led to multiple periods of borrowing, default, and setbacks to growth as the nation struggled to repay its debts. The record-setting level of the current debt makes Greece extremely fragile and vulnerable to unforeseen circumstances. [1] “This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly”, Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff, Princeton University Press, 2011. [2] “State Insolvency and Foreign Bondholders: Selected Case Histories of Governmental Foreign Bond Defaults and Debt Readjustments”, William H. Wynne, 1951, p. 298. [3] Ibid. p. 298. [4] Ibid p. 304 [5] Ibid. p. 271. [6] “Foreign Loans at the birth and development of the New Greek State 1824-2009,” T. M. Hliadakis, 2011, Mpatsioulas Publishers, p. 364. [7] Ibid. Page 393. [8] Ibid. Page 419.The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any policy or position of the New York State Assembly.