Merih Uctum and Zhuo Xi

September 22, 2018

On August 9 the Turkish currency, the Lira, hit record lows and rattled emerging markets. The travails of the Argentinian economy subsequently weakened the Lira further. In this analysis article, we examine the economic and financial reasons behind the turmoil the economy is going through and discuss the future path it may take.

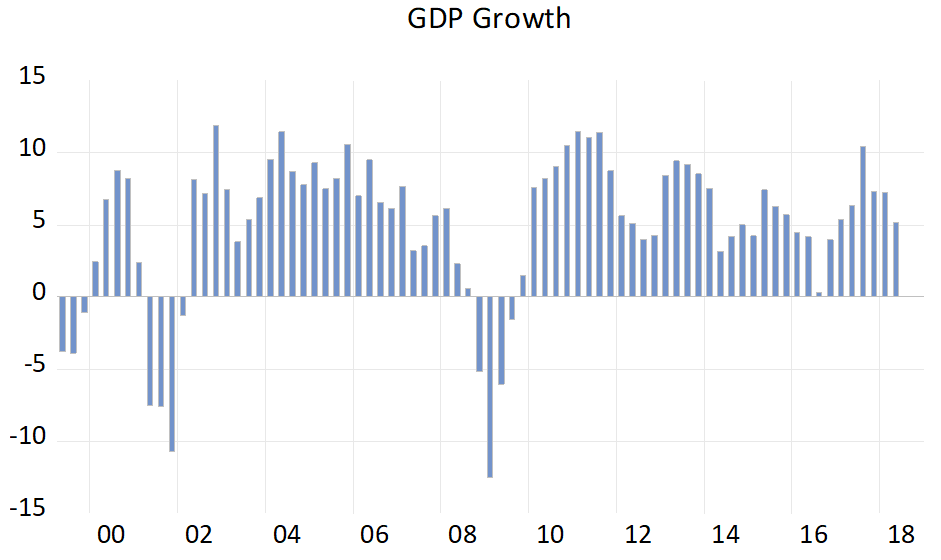

Following the sound economic policies adopted in the wake of the twin crises of the early 2000s, the economy experienced solid growth, except during the 2007-8 global financial crisis. Since 2010, the economy has averaged a healthy annual growth rate of 6.85% despite a slowdown since 2017.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

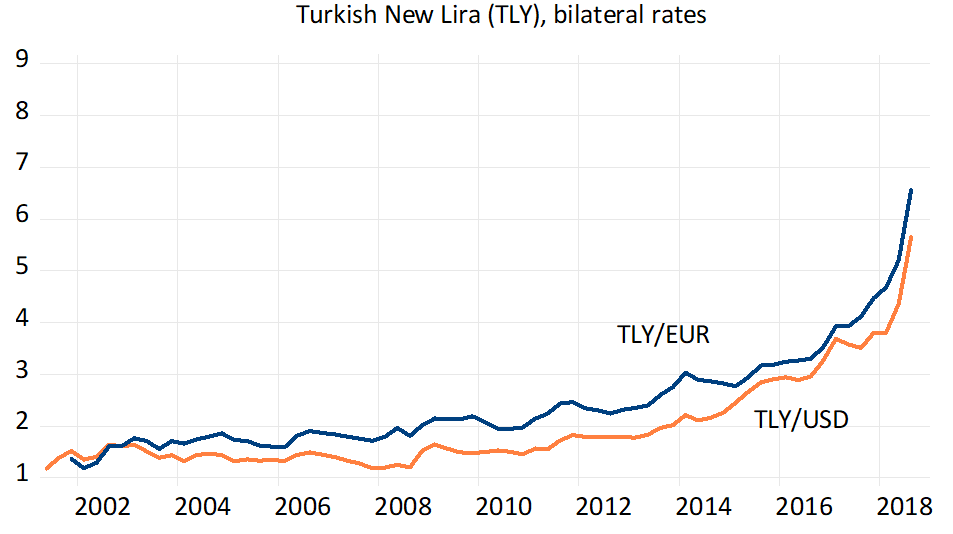

But the recent collapse of the currency was dramatic and does not square with the strong performance of the economy. Since 2008 the Lira depreciated by 82% against the dollar and 76% against the euro:

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

After hitting a historic low on August 13 of 7.0 Lira against the dollar and 7.93 against the euro, belated minor measures by the Central Bank of Turkey and a pledge of $15 billion worth of investment by Qatar in Turkey, the currency stabilized briefly before being hit again on August 18 as contagion from Argentina spread to other fragile currencies.

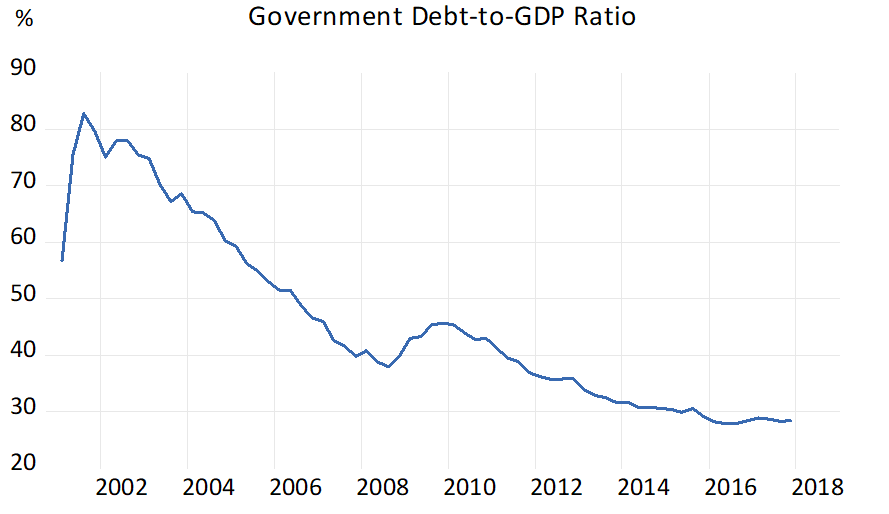

Public debt is usually one of the culprits in economic crises. However, in Turkey this is not the case at hand. While public finances in Western economies and in several emerging markets went into large deficits after 2008, and many are still struggling to reduce it, Turkish government debt has declined and been hovering at a modest 30% of GDP.

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

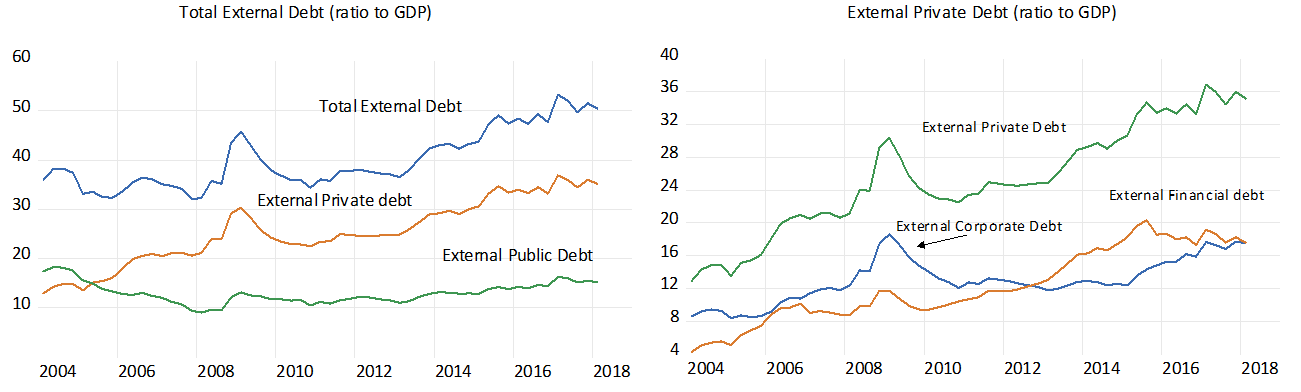

The story of the Turkish currency crisis, however, repeats a familiar scenario of emerging market crises. In an environment with ultra-low interest rates, strong growth in the economy is fueled by borrowed funds by the private sector, mostly from international capital markets.

During the first quarter of 2018, total external debt stock climbed to $466.67 bn, about half of GDP, with private debt making up 70% of it. Both the financial and nonfinancial (mostly corporate) sectors have been borrowing heavily since 2010. After ballooning during the financial crisis, corporate debt declined and steadied around 12% of GDP but rose steeply by 70% for the last three years. Foreign borrowing of financial institutions and banks continued and surpassed that of the corporate sector.

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

Although banks’ external roll over ratios (long-term external borrowing/repayments) are at a five-year low, rising interest rates in the West and a depreciating currency may generate sufficient risk to discourage lending by foreign banks.

Due to “original sin,” a term describing the fact that emerging markets economies cannot borrow in their own currency but only in foreign currency, usually US dollars, any event that triggers a depreciation of the currency and/or a rise in interest rates aggravates the foreign currency-denominated debt burden, when translated into the local currency. While various factors have been contributing to the accelerating depreciation of the Turkish Lira, it is the recent conflict with the United States that triggered the run on the currency.

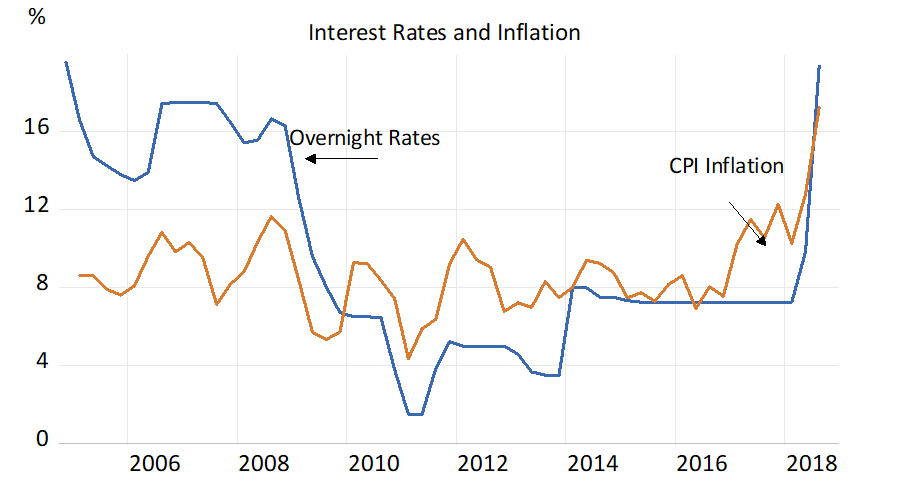

Depreciation of a currency has several consequences on an economy. One beneficial impact is to stimulate exports over a certain period, but another dire and more immediate effect is to exacerbate inflation, which can undo the benefits of the first impact. In an economy dependent on oil imports and with endemic inflation, as in Turkey, the influence of depreciation on prices has been swift and painful.

August data indicate that consumer price inflation reached 17.9%, more than quadrupling since the end of the financial crisis in 2009.

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

The conventional response of policymakers in such a situation is to raise interest rates, reschedule the external debt and implement austerity measures. However, policymakers in Turkey had been reluctant to change rates aggressively or to start discussions with the IMF. For comparison, Argentina, which is in the throes of a financial crisis, increased rates to more than 60% and is preparing to receive guidance from the IMF. After the long-awaited increase in the one-week repo rate by 625 basis points last week to 24 %, an increase above the expectations of the markets, the currency stabilized but several dark clouds in the horizon suggest further trouble ahead.

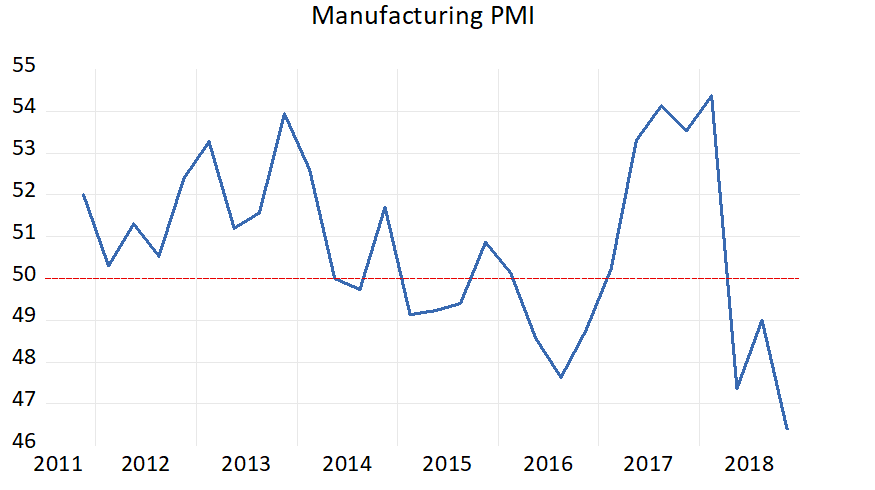

Leading indicators point to decreased confidence among households and businesses. The Purchasing Managers’ Index in manufacturing took a plunge since the beginning of the year, falling to 46.4 and creating further jitters in markets.

Source: Istanbul Chamber of Industry and HIS Markit

Source: Istanbul Chamber of Industry and HIS Markit

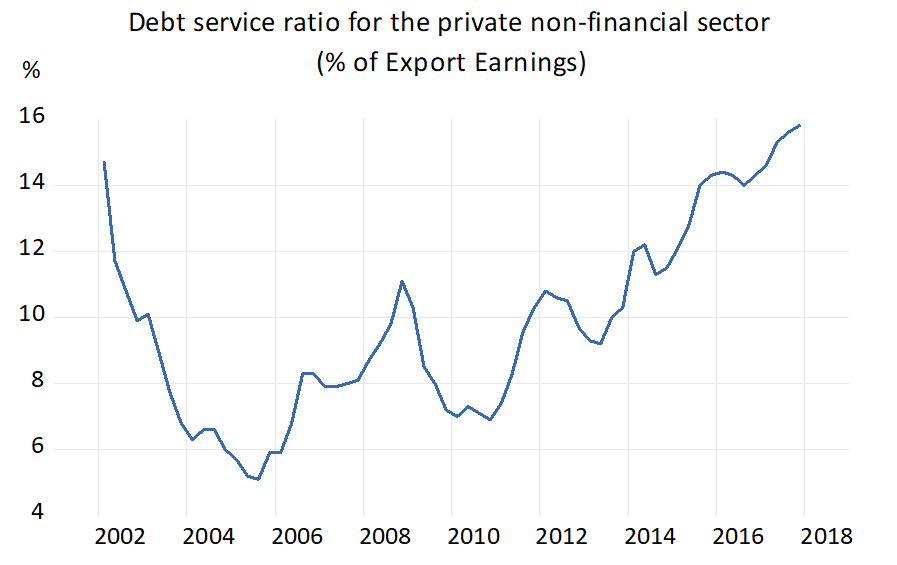

Total debt service as a percentage of exports is a measure used to assess sustainability of a country’s debt burden. Turkey’s debt service ratio increased continuously since 2013 and surpassed its 2002 crisis level for the first time at the end of 2017. Tightening by the Federal Reserve Bank, which is also likely to be followed by the European Central Bank, will continue to worsen the debt burden of the country.

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

It took two crises (2000 and 2001) followed by serious economic reforms and austerity measures to bring down inflationary expectations in Turkey. These policies earned back the confidence of markets, with an influx of foreign direct investment and access of the country to international financial markets. The recent events might have done damage to the economic progress achieved so far.

Currently, the main concern of market participants is the contagion of the Turkish crisis to similar economies with large foreign debt levels and to international banks that lent to Turkey. During August, the Turkish Lira dragged down the currencies of several emerging economies such as Argentina, South Africa, Brazil, Russia and India against the dollar, which reached their lowest levels since May. The European Central Bank expressed concern about the impact that a plummeting Turkish currency could have on Spanish, French and Italian banks that are holding Turkish assets. Another concern is about borrowers in Turkey who might start defaulting on their debt. Both of these events could hurt European banks.

The problems discussed above necessitate concerted and committed effort by the government to contain the currency and debt crises. International financial markets are bracing for hard times ahead.