Meng-Ting Chen and Joseph van der Naald

November 16, 2018

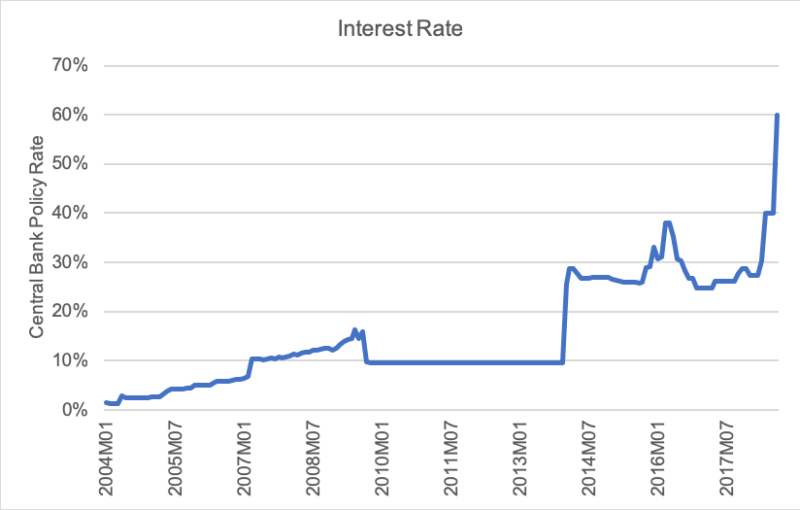

Following a stunning fall in the value of its peso, a total loss of nearly 50% for 2018, and interest rates hitting 60%, Argentina’s economy appeared to be facing the strong likelihood of a crisis. While the government responded by taking a number of measures to calm the markets for the time being, the roots of Argentina’s crisis are complex. In this article, we outline the economic precursors to the Argentinian financial crisis and examine the steps being taken to address the situation. The country recently accepted a $57.1 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), temporarily stabilizing the situation. The administration of President Mauricio Macri has agreed to economic reforms, including spending cuts of 1.4% and revenue increases of 1.2% of GDP. The Central Bank is also keeping the nominal money supply constant with the objective of slowing inflation.

Though Argentina’s adjustments have partially restored investor confidence, the future remains uncertain. Emergency funds from the IMF signal confidence in Argentina, and yet both the Fund and Moody’s is predicting a considerable contraction in the economy in the coming year. Further, rising interest rates in the United States threaten Argentina’s situation as dollar-denominated debt becomes harder to repay. This crisis has been characterized as the potential beginnings of a “textbook” emerging-market crisis, caused by considerable short-term external debt in tandem with a budget deficit, and a current-account deficit.

The Genesis of the Crisis

Argentina’s current crisis has its roots in economic policies of crises past. During the four-year Argentine Great Depression of 1998 to 2002, the peso was pegged to the US dollar and the Argentine government imposed a set of capital controls known as “el corralito,” restricting bank account activity and prohibiting withdrawals from U.S. dollar-denominated accounts. With the official rate fixed and currency exchange restricted, these controls contributed to the emergence of twin exchange rates: one official and the other a much lower black market rate.

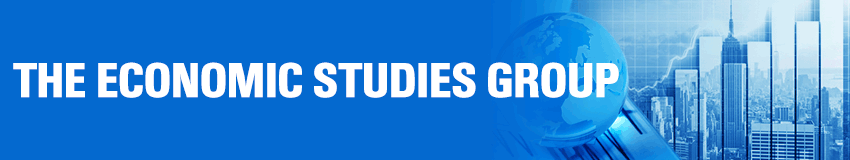

Economic growth in the decade that followed was weak, averaging a little less than 1.0 percent annually, although with sharp declines in the 2008 global financial crisis and again in 2012. Since 2012, annual growth rates have generally been less than 0.5%., with a sharp decline in the first quarter of 2018.

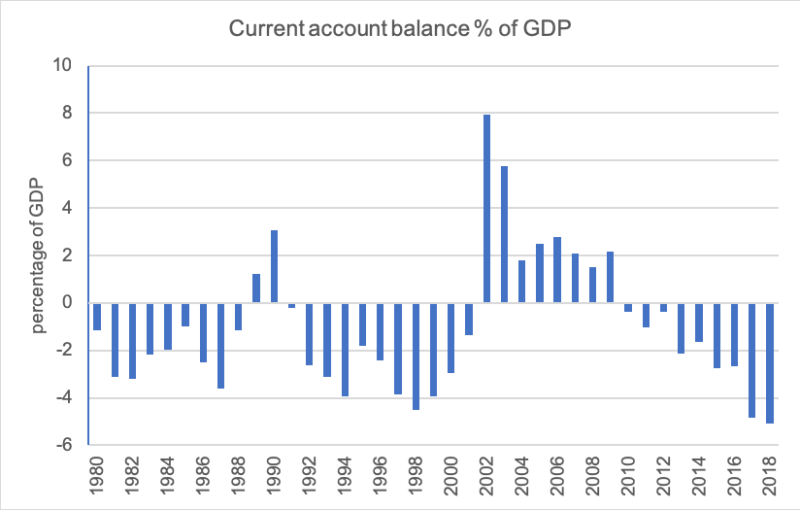

Source: Global Economic Monitor, World Bank

During the administrations of Presidents Néstor and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2003 – 2015), the slowing GDP growth rates coincided with a dramatic increase in public expenditure, reaching over 41% of GDP in late 2015. Government budget deficits exceeded 1.5% of GDP in eight of the past ten years. In 2002, Argentina had a trade surplus of $8.6 billion, which accounted for 16% of GDP, yet after a decade of protectionism, which threw key sectors into disarray with high tariffs suffocating agricultural exports and import restrictions putting the country at odds with global trading partners, this surplus had eroded into a deficit by 2015. Further, the Fernández de Kirchner administration imposed additional capital controls to prevent the flight of “hot money,” exacerbating the gap between the black market exchange rate, “dólar blue,” and the official exchange rate.

Efforts to Address the Crisis

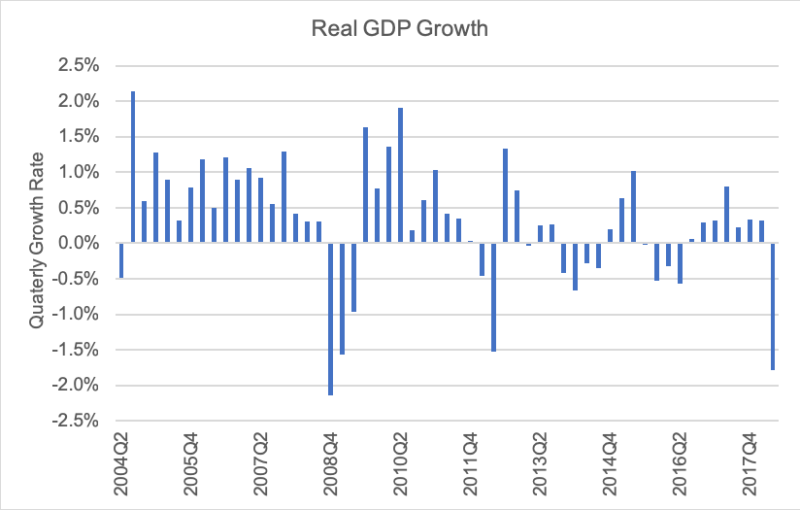

As the Macri administration assumed power in 2015, Argentina faced a number of challenges. The issue of the dual exchange rates was addressed by the imposing of a flexible exchange rate. While official exchange rate initially depreciated to meet the black market rate, depreciation soon accelerated thereafter.

Source: Bank for International Settlements

Rather than engaging in money creation, the Macri administration sought deficit financing in international capital markets. This increased Argentina’s vulnerability to both currency devaluation and further external financing opportunities, and in 2017 a variety of factors from rising US Federal Reserve interest rates to a terrible drought, set the currency into a downward spiral. While a depreciated peso could help the economy through increased exports, it also has important implications for debt financing and inflation. Most of Argentina’s debts are issued in US dollars, the so-called “original sin.” As the government engages in external deficit financing with foreign currency debt, and as the value of the peso drops, these debts become harder to pay off increasing investors’ fears of default. Investors then began selling these debts fostering a further drop in the value of the peso.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2018

Inflation, after holding steady through 2012, has been in excess of 20% in each of the past four years, in part the result of the declining peso and rising import prices. Upon taking office, Marci returned monetary independence back to the Central Bank, which began tightening monetary policy in an attempt to lower inflation. One of the ways by which the Central Bank has sought to decrease inflation is through the sale of Central Bank bonds (LEBACS). Yet, as the peso depreciates, bonds issued previously are more difficult to repay. In turn, the Central Bank increased its interest rates to attract more lenders, raising its rates to an unprecedented high of 60% in August 2018, which effectively increasing existing debts to pay old ones, creating a snowball of central bank bonds.

Source: Bank for International Settlements

The $57.1 billion credit line from the IMF is intended to reassure investor confidence; however, the credit line demands a budget deficit reduction through fiscal austerity and a narrowing of the capital-account deficit. Argentine authorities have committed to accelerating the process of fiscal convergence and plan to meet these goals in two ways. First, it is slashing operating expenses, subsidies, and infrastructure. Second, it will introduce temporary export taxes on goods and services to increase revenue. In addition to these tough fiscal steps, the Central Bank is overhauling its monetary policy, as it switches to targeting monetary aggregates as its new nominal anchor. This strong monetary contraction is likely to be effective in slowing down inflation; however, if it is too effective, it is likely to deepen the recession. The exchange rate will be allowed to float within a target zone of 33 to 44 pesos to the dollar and the Central Bank will intervene in foreign exchange markets only if the exchange rate crosses this predetermined mark.

Macroprudential Policy

In the short run, Argentine policymakers could proactively enforce capital controls to stem the risks of rapid capital outflows. Accompanied by new monetary policy and a flexible exchange rate regime, both imposing controls on inflows and outflows of capital has been proven an effective prudential policy for most of emerging market economies. Controls on outflow prevent the risk of crises, while controls on inflow can insulate Argentina from external shocks. Moreover, Argentine overborrowing due to the “original sin” exposes the economy to external shocks that can cause a “sudden stop.” Taxation of privately held foreign-currency denominated assets and/or the incomes those assets generate can preventcountries from overborrowing and reduce the probability of financial crisis.

The analysis above provides context to the needed interventions that the government should make in order to mitigate the worst aspects of the crisis’ fallout. Moreover, as the likelihood of a global emerging markets crisis increases the state must prioritize efforts to insulate the economy against further instability.