Paul Krugman

August 30, 2019

Remember the Vietnam quagmire? In political discourse, “quagmire” has come to have a quite specific meaning. It’s what happens when a government has committed itself to a policy that isn’t working but can’t bring itself to admit failure and cut its losses. So, it just keeps escalating, and things keep getting worse.

Well, here’s my thought: Trump’s trade war is looking more and more like a classic policy quagmire. It’s not working — that is, it isn’t at all delivering the results Trump wants. But he’s even less willing than the average politician to admit to a mistake, so he keeps doing even more of what’s not working. And if you extrapolate based on that insight, the implications for the U.S. and world economies are starting to get pretty scary.

To preview, I’m going to make five points:

- The trade war is getting big. Tariffs on Chinese goods are back to levels we associate with pre-1930s protectionism. And the trade war is reaching the point where it becomes a significant drag on the U.S. economy.

- Nonetheless, the trade war is failing in its goals, at least as Trump sees them: the Chinese aren’t crying uncle, and the trade deficit is rising, not falling.

- The Fed probably can’t offset the harm the trade war is doing and is probably getting less willing even to try.

- Trump is likely to respond to his disappointments by escalating, with tariffs on more stuff and more countries, and — despite denials — in the end, with currency intervention.

- Other countries will retaliate, and this will get very ugly, very fast.

I could, of course, be wrong. But that’s how it looks given what we know now.

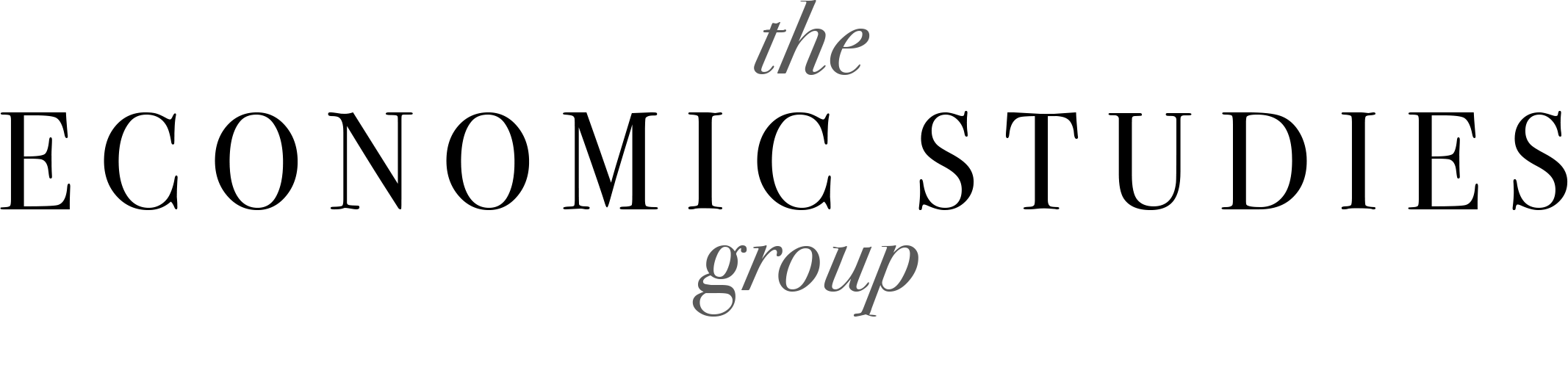

Let’s start with the scale of the policy. The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) generated a nice chart showing the escalation of tariffs on Chinese goods under Trump:

Average US tariff rates on imports from China before and after President Trump’s acts of protection

Source: PIIE

So roughly speaking, we’ve seen a 20 percent tax imposed on the $500 billion worth of goods we import from China each year. Although Trump keeps insisting that the Chinese are paying that tax, they aren’t. When you compare what has happened to prices of imports subject to new tariffs with those of other imports, it’s overwhelmingly clear that the burden is falling on U.S. businesses and consumers.

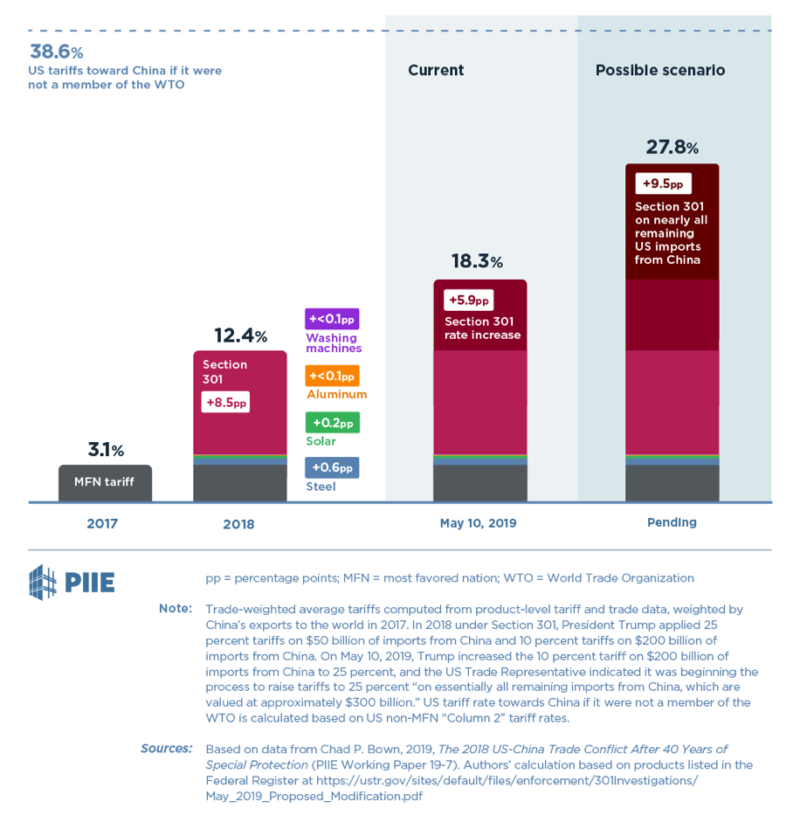

So that’s a $100 billion a year tax hike. However, we aren’t collecting nearly that much in extra tariff revenue:

Customs duties receipts (in billions of Dollars)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Partly that’s because the revenue numbers don’t yet include the full range of Trump tariffs. But it’s also because one big effect of the Trump tariffs on China has been to shift the sourcing of U.S. imports — e.g., instead of importing from China, we buy stuff from higher-cost sources like Vietnam. When this “trade diversion” happens, it’s still a de facto tax increase on U.S. consumers, who are paying more, but it doesn’t even have the benefit of generating new revenue.

So, this is a pretty big tax hike, which amounts to contractionary fiscal policy. And we should add in two other effects: foreign retaliation, which hurts U.S. exports, and uncertainty: Why build a new factory when for all you know Trump will suddenly decide to cut off your market, your supply chain, or both?

I don’t think it’s outlandish to suggest that the overall anti-stimulus from the Trump tariffs is comparable in scale to the stimulus from his tax cut, which largely went to corporations that just used the money to buy back their own stock. And that stimulus is behind us, while the drag from his trade war is just getting started.

But why is Trump doing this? A lot of center-right apologists for Trump used to claim that he wasn’t really fixated on bilateral trade balances, which every economist knows is stupid, that it was really about intellectual property or something. I’m not hearing that much anymore; it’s increasingly clear that he is, indeed, fixated on trade balances, and believes that America runs trade deficits because other countries don’t play fair.

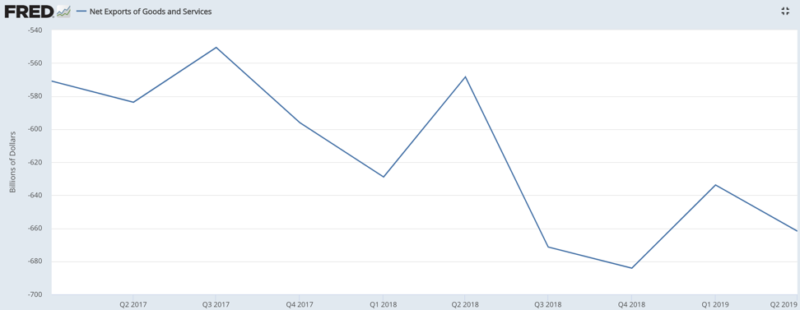

Strange to say, however, despite all those new tariffs the U.S. trade deficit is getting bigger, not smaller, on his watch:

US net exports of goods and services (in billions of dollars)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

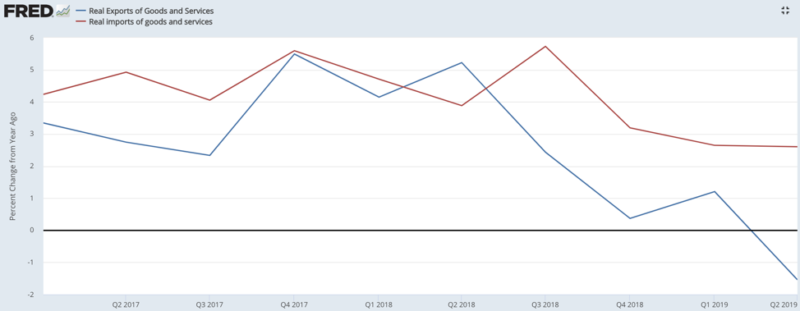

Adjusted for inflation, imports are still growing strongly, while U.S. exports have been shriveling:

Year-over-year percentage change in real (inflation-adjusted) exports and imports of goods and services

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Why aren’t tariffs shrinking the trade deficit? Mainly the answer is that Trump’s theory of the case is all wrong. Trade balances are mainly about macroeconomics, not tariff policy. In particular, the persistent weakness of the Japanese and European economies, probably mainly the result of shrinking prime-age work forces, keeps the yen and the euro low and makes the U.S. less competitive.

When it comes to recent import and export trends, there may also be an asymmetric effect of the tariffs themselves. As I already mentioned, U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods don’t do much to reduce overall imports, because we just shift to products from other Asian economies. On the other hand, when the Chinese stop buying our soybeans, there aren’t any major alternative markets.

Whatever the explanation, Trump’s tariffs aren’t producing the results he wanted. Nor are they getting the other thing he wants: Splashy concessions from China that he can portray as victories (“tweetable deliveries”). As Gavyn Davies says, China seems “increasingly confident it can weather the trade wars,” and it’s not showing any urge to placate the U.S.

So, this might seem to be a good time to hit the pause button and rethink strategy. Instead, however, Trump went ahead and slapped on a new round of tariffs. Why?

Well, stock traders reportedly think that Trump was emboldened by the Fed’s rate cut, which he imagines means that the Fed will insulate the U.S. economy from any adverse effects of his trade war. We have no way of knowing if that’s true. However, if Trump does think that, he’s almost surely wrong.

For one thing, the Fed probably doesn’t have much traction: interest rates are already very low. And the sector most influenced by interest rates, housing, hasn’t shown much response to what is already a sharp drop in mortgage rates.

Furthermore, the Fed itself must be wondering if its rate cut was seen by Trump as an implicit promise to underwrite his trade war, which will make it less willing to do more — a novel form of moral hazard.

There is, by the way, a strong contrast here with China, which for all its problems retains the ability to pursue coordinated monetary and fiscal stimulus to a degree unimaginable. Trump probably can’t bully the Fed into offsetting the damage he’s inflicting (and just try to imagine him getting Nancy Pelosi to bail him out); Xi is in a position to do whatever it takes.

So, what will Trump do next? My guess is that instead of rethinking, he’ll escalate, which he can do on several fronts. He can push those China tariffs even higher. He can try to deal with trade diversion by expanding the trade war to include more countries (good morning, Vietnam!).

And he can sell dollars on foreign exchange markets, in an attempt to depreciate our currency. The Fed would actually carry out the intervention, but currency policy is normally up to the Treasury Department, and in June Jerome Powell reiterated that this is still the Fed’s view. So, we might well see a unilateral decision by Trump to attempt to weaken the dollar.

But a deliberate attempt to weaken the dollar, gaining competitive advantage at a time when other economies are struggling, would be widely — and correctly — seen as beggar-thy-neighbor “currency war.” It would lead to widespread retaliation, even though it would also probably be ineffective. And the U.S. would have forfeited whatever remaining claims it may still have to being a benevolent global hegemon.

A version of this article has been originally published in New York Times on 3/08/2019