The New York City Labor Market: Recent Developments

James Orr

April 04/Revised April 09, 2017

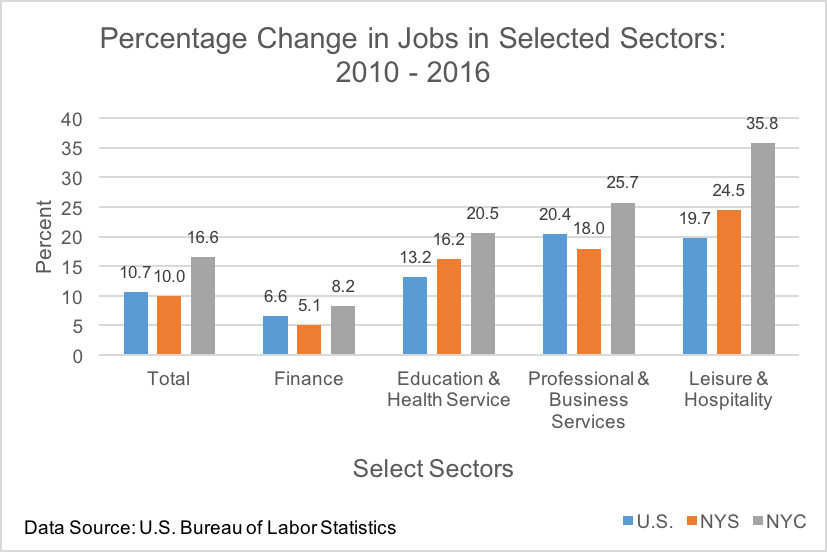

Recently-revised employment data show New York City jobs grew 2.2 percent in 2016, more than 90,000 jobs, well above the national growth rate of 1.8 percent and statewide growth of 1.5 percent. The relatively strong job performance in the city compared to the nation did not develop recently but has been a consistent feature of the recovery and expansion of employment from its cyclical low in 2010. The strength of the city’s job growth is even more remarkable in that it contrasts sharply with the considerably deeper decline and slower recovery of employment in the city compared to the nation in the prior cycle. This post looks at the city‘s job growth following the 2008-2009 downturn and delves further into several labor market developments in the city that have supported, and been supported by, this rapid job growth.

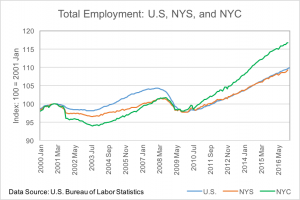

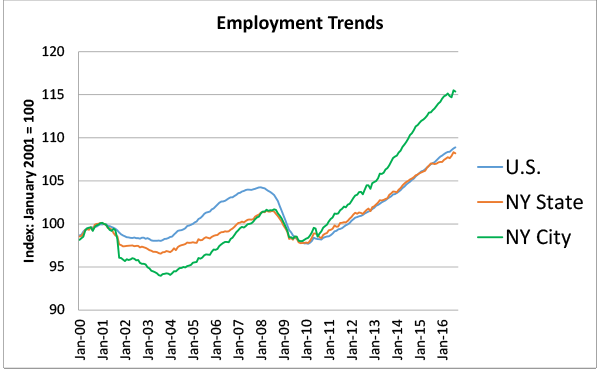

The figure below, adapted from an earlier presentation, presents an index of monthly employment levels from 2000 to 2016 in New York City, New York State and the nation. Almost from the start of the recovery of jobs in 2010, the job growth rate in New York City exceeded that of the nation and has pushed the level of employment well above both its cyclical low and its peak employment level in the previous cycle. A measure of overall economic activity in the city also shows a relatively mild downturn and robust recovery beginning in late 2009. Statewide employment growth has closely matched that of the nation, indicating relatively weaker job performance in other parts of the state. The upturn is also remarkable in that it reverses the pattern seen in the downturn of the early 2000s. Then, the city’s employment losses were significantly deeper than that of the nation. Of course, the 9/11 attack occurred just after the downturn began which further weakened employment in the city’s economy, in general, and Lower Manhattan in particular. At that time, a full recovery to pre-downturn levels in the city didn’t occur until almost three years after the nation had recovered.

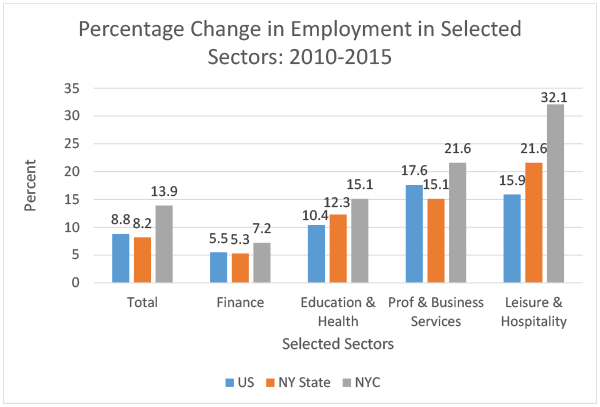

Three significant developments have accompanied this relatively rapid growth of jobs in the city since 2010. The first is the fact that the expansion of jobs has not been led, as it has been in prior recoveries, by job growth in the city’s key financial sector. While still a major force in the city’s economy, generating about a fifth of total city earnings, jobs in the sector have increased only modestly over this period, and as a result the finance sector’s share in total employment in the city has declined over the period. Key sources of growth have been an array of traditional services sectors, including the education and health and leisure and hospitality sectors, which are important sources of employment across the city and where growth has significantly outpaced that of the nation. Construction and retail trade have also grown fairly robustly in this upturn, and there has been dramatic growth in the city’s tech sector. While there is no established definition of the component of the tech sector, a recent report aggregated jobs in a number of sectors where the firms used technology as the core of their business strategy. That report showed that tech jobs defined in this way more than doubled between 2007 and 2014 and contributed significantly to the city’s overall job growth.

A second development is that from 2010 to 2014 the city’s population expanded 4.6 percent, supported by positive net migration, and the annual average rate of growth was stronger than any seen in the city since the 1920s. The rapid population growth over this period was also a sizeable increase over the growth rate recorded in the city over the prior decade. This rapid growth is also consistent with the notion of an increasing attractiveness of urban areas more generally, and recent population growth rates in a number of big cities has been considerably faster than in the prior decade, and earlier, including Los Angeles, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Dallas and Washington, D.C.

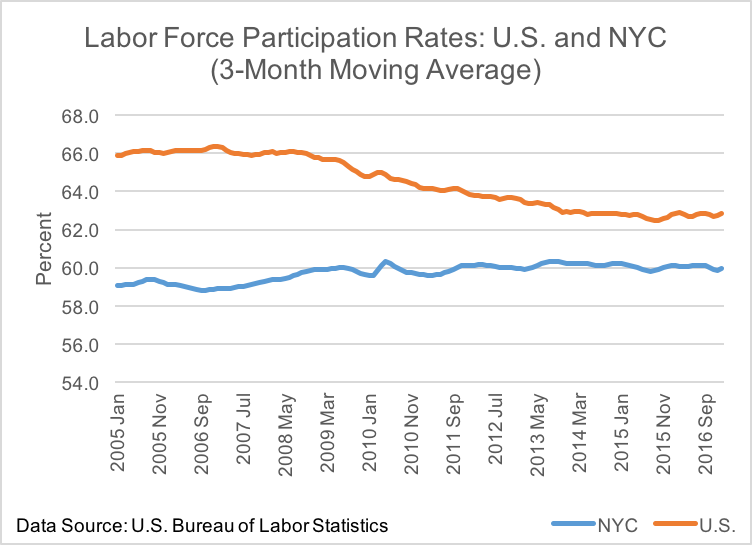

Third, the labor force participation rate in the city has not been declining. Nationally, the labor force participation rate, or the share of the population that participates in the labor force, has been problematic in this cycle. On an annual average basis, the rate fell from its pre-recession value of about 66.0 percent to a low of 62.7 percent in 2015 before turning up. In New York City, the participation rate, while below that of the nation, rose modestly from 59 percent in 2007 to 60 percent in 2010 and then has remained at roughly that rate to the present. Unlike the nation where demographics—the aging of the population—contributed to the declining participation rate, a recent report suggests a key part of the reason for rising labor force participation rates in the city since 2010 is also demographics—the city’s younger population with relatively high rates of labor force participation.

While the high participation in the labor force is encouraging, a measure of how New York residents are faring from the rapid employment growth is the unemployment rate, or the share of the labor force without jobs. The city’s 5.2 percent average unemployment rate in 2016, though well off its peak rates in 2010, was moderately above the 4.9 unemployment rate in the nation. Alternative estimates of the underutilization of labor for the nation and New York City are now reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The broadest of these measures, termed U-6, includes with the unemployed discouraged workers, those who want work but did not actively look in past four weeks and also those who want full-time work but are working part-time for economic reasons. The 9.6 percent rate in New York City for all of 2016, a similar rate as the nation as a whole, is much higher than the unemployment rate, suggesting there remain residents who can take advantage of a further expansion of job opportunities in the city.

Looking ahead, several indicators suggest a slowing in the employment expansion in New York City. While still fairly high, job growth in the city in recent months has slowed from its 2015 pace. Forecasts of job growth point to a deceleration in 2017 with some heightened policy uncertainty. Annual job growth rates are projected to continue their decline though they are still expected to be in the range of 0.7 to 1.0 percent in 2020. It will be important to track the city’s population and labor force trends should an environment of sharply decelerating growth develop.