Timothy Goodspeed

January 06, 2017

The revelation of the first page of Donald Trump’s 1995 tax return during the 2016 election campaign by the NY Times created a large controversy. At first glance the public may wonder about two issues: (1) why does the tax code allow a company’s losses to be carried over to other years, and (2) why does our tax system allow business losses to appear on a personal income tax return? The answers raise some fundamental issues in tax design.

Why are companies allowed to carryover losses from one year to the next?

The US tax code has for a long time allowed a company’s losses to be spread over many years to calculate its annual taxable income. Current law allows a company’s losses to be carried forward or backward. These carrybacks and carryforwards can be up to 20 years total (from 2 years back and up to 20 years forward; state rules differ as well). They are commonly used by companies that have losses in a given year. Indeed, Table 1 shows that the tax code of most countries allows for some redistribution of losses across years, often with carryforwards more generous than the US. The first question is why would the tax code allow a company’s losses to be shifted through time by carrybacks and carryforwards?

Part of the answer is that taxes are calculated on an annual basis but companies make purchases of equipment or other expensive investments that are geared towards generating a stream of revenue over many years. The large upfront costs may themselves lead to losses in the initial years after the purchase and/or the revenue stream from the investment may be variable.

The company makes the investment because it believes that over time the accumulated revenue will add up to more than the initial capital expense and positive profits will be generated. One question then is how to match up the initial expenses of the capital equipment with the stream of revenue that it produces in the future on an annual basis so that profits can be taxed annually. If a business is making positive profits we use capital depreciation rules which allow a firm to deduct a certain amount of its capital equipment each year over the life of the equipment. However, if a firm is making a loss, it will not have any income to tax so any deduction in that year would be worthless. Allowing loss deductions to be spread over time is a common method used to overcome this problem.

Table 1: Net Operating Loss Carryback and Carryforward Rules around the World

| Country | Loss Carry-back | Loss carry-forward |

| Australia | No | Indefinite |

| Austria | No | Indefinite |

| Canada | 3 years | 20 years |

| Denmark | No | Indefinite |

| France | 3 years | Indefinite |

| Germany | 1 year | Indefinite |

| Ireland | 1 year | Indefinite |

| Italy | No | 5 years |

| Mexico | No | 10 years |

| Netherlands | 1 year | 9 years |

| New Zealand | No | Indefinite |

| Norway | No | Indefinite |

| Spain | No | 15 years |

| Sweden | No | Indefinite |

| Switzerland | No | 7 years |

| United Kingdom | 1 year | Indefinite (against profits of the same trade) |

| United States | 2 years | 20 years |

Source: OECD (2011) Corporate Loss Utilisation through Aggressive Tax Planning, OECD Publishing.

How can business losses show up on a personal tax return?

The second issue is why Donald Trump’s loss appears on his personal tax form. The US tax code allows a company to be set up in several different forms that have different tax and legal consequences. Before 1958 there were essentially two options: set up as a C-corporation with limited liability or set up as a sole proprietor or partnership without limited liability. C-corporation profits are taxed twice, however, once at the corporate level and then again at the personal level. Taxes on the sole proprietor or partnership are only imposed once, at the individual level. These latter organizations are known as “pass-through” entities since their income passes through to the ultimate owner for tax purposes. A third type of pass-through entity, the S-corporation, was established by Congress in 1958 to try to allow small (often family) businesses to benefit from limited liability and at the same time be taxed only once at the individual level. Use of the S-corporate form has restrictions, though; for instance the number of shareholders is limited (currently no more than 100 and more restricted in earlier years).

The integration of the personal and corporate tax systems is often sought after to eliminate the double taxation of corporate income. Countries use different methods to achieve this but many allow a credit of corporate taxes when individuals receive income from a corporation. Pass-through entities (S-corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships) result in a partial integration of the personal and corporate tax codes in the US, but also provide avenues for tax avoidance and have implications for the overall equity of the tax system.

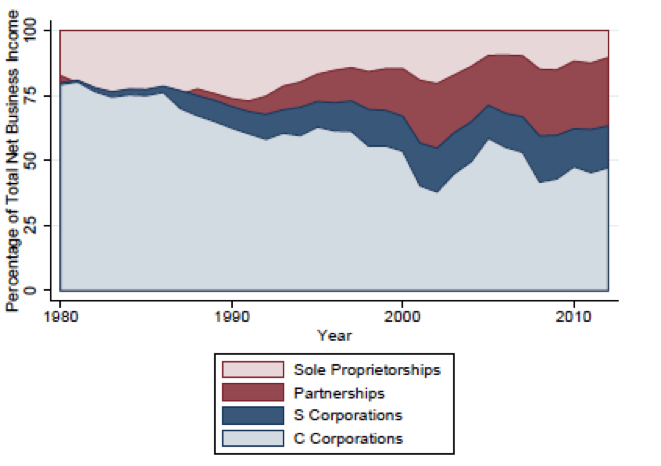

As chart 1 shows, pass-through entities as a form of business organization are of growing importance in the US. A substantial expansion of pass-through entities occurred after the 1986 Tax Reform Act but has accelerated in recent years. In 1985 S-corporations numbered 725,000 with about 4 percent of business net income; today they number over 4 million with almost 15 percent of business net income. Even faster growth occurred in partnerships. The partnership share of net business income rose from a bit over 2 percent in 1980 to 26 percent in 2012.

Chart 1: The Growth of Pass-Through Entities in the US 1980-2012

Source: Cooper, McClelland, Pearce, Prisizano, Sullivan, Yagan, Zidar, Zwick “Business in the United States: Who Owns it and How Much Tax Do They Pay?” in Tax Policy and the Economy, Cambridge: MIT Press, Vol 30: 90-128, Brown. 2016, (data from DeBacker and Prisizano, “The Rise in Partnerships,” Tax Notes, June 29, 2015, p. 1563).

Source: Cooper, McClelland, Pearce, Prisizano, Sullivan, Yagan, Zidar, Zwick “Business in the United States: Who Owns it and How Much Tax Do They Pay?” in Tax Policy and the Economy, Cambridge: MIT Press, Vol 30: 90-128, Brown. 2016, (data from DeBacker and Prisizano, “The Rise in Partnerships,” Tax Notes, June 29, 2015, p. 1563).

Future Tax Policy Changes?

As Donald Trump enters office, tax policy change is high on the agenda. Proposals are on the table to reform our corporate, international, and individual tax systems. However, the new policies turn out, they will be sure to have a large impact on companies, employment, wages, income distribution, and economic growth.