James Orr

Jun 09, 2017

Finance has long been considered a key sector in the New York City economy. The sector generates about 30 percent of the earnings of workers throughout the city, and thus developments in the sector are critically important for the performance of the overall city economy. This post reviews the recent changes in the sector in New York City, particularly the securities segment, and discusses some of the ongoing challenges faced by the city as a host to financial firms.

The finance sector, formally labeled Finance and Insurance, consists of four major industries: Credit Intermediation (informally banking), Securities, Commodity Contracts and other Financial Investments (the securities sector or Wall Street), Insurance, and Funds, Trusts and Other Financial Vehicles. In terms of jobs, the sector employs about 460,000 workers, a little less than 10 percent of city employment, with banking and securities comprising about three-fourths of the jobs with the sector.

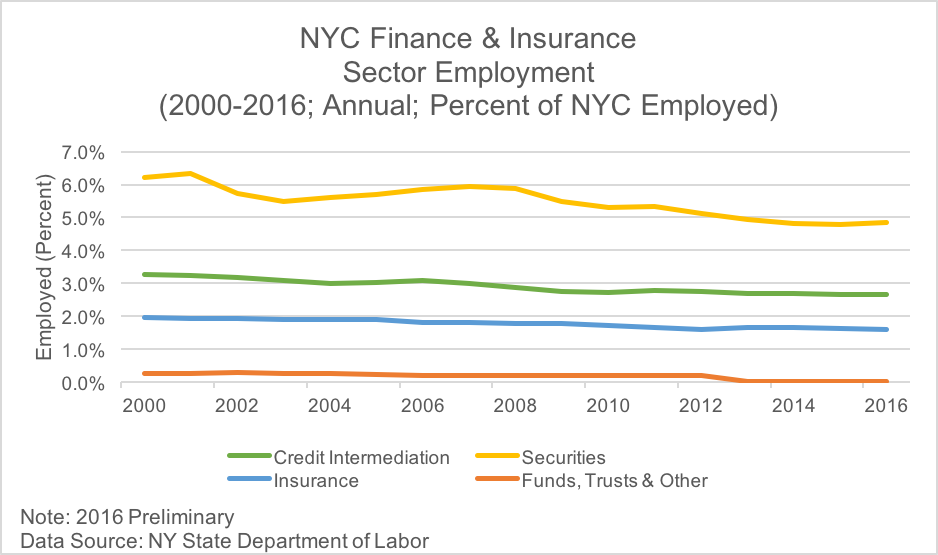

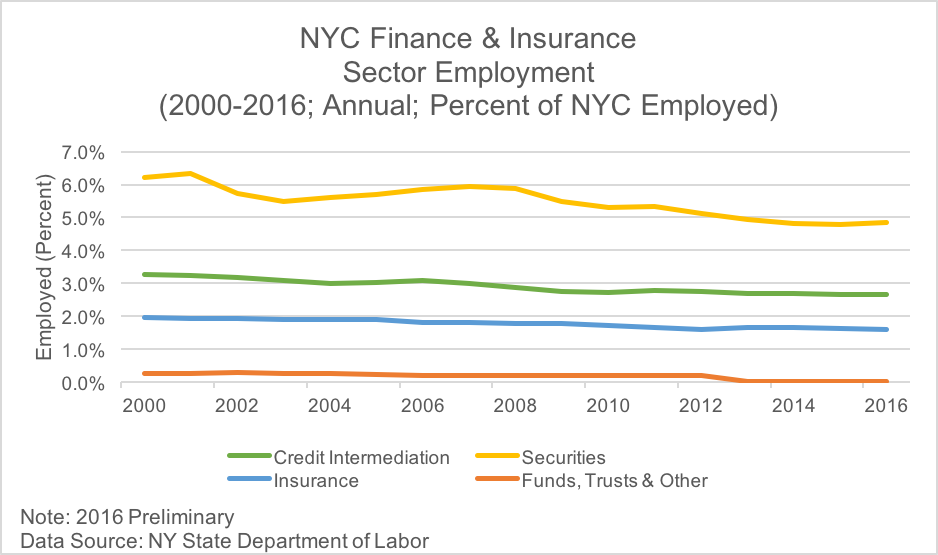

Since 2000, employment in the Finance and insurance sector in New York City has declined in absolute terms by about 30,000 jobs. As seen in the chart below, the share of total city employment in securities fell from over six percent to a little under five percent, while the shares of employment in the other sub-sectors declined only modestly over the period. Many factors underlie this absolute and relative decline in jobs, principal among them are the long-term trend in the outmigration of relatively low value-added activities across the sector to cheaper alternative locations, the increasing use of technology in providing financial services and, most recently, the strong expansion of jobs in non-financial industries in the city, such as health and education, tourism, and professional and business services. The figure also indicates a decline in the share of employment in the securities industry in the two years following the 9/11 attack in 2001 and for several years following the financial crisis in 2008. In neither case did the sector fully recover its prior peak employment share.

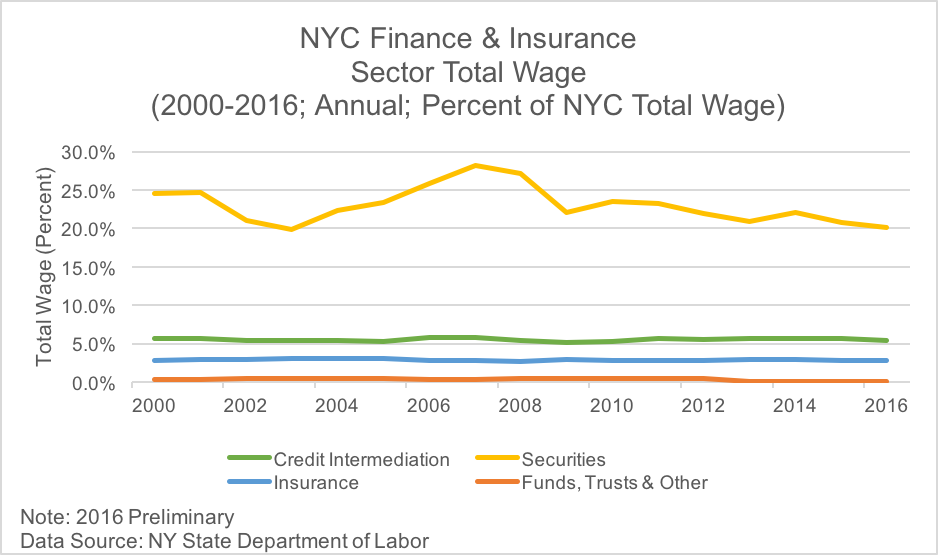

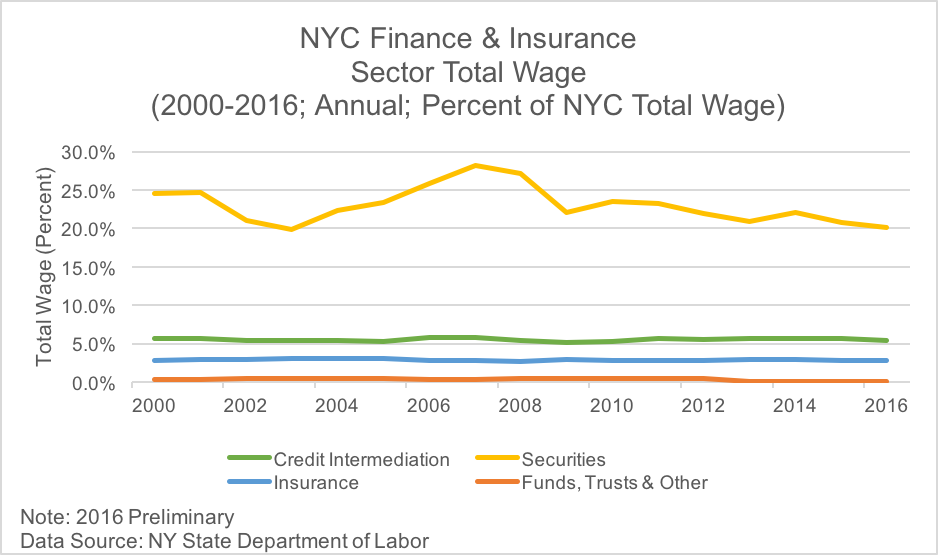

Despite what appears as a relatively moderate and declining share of employment, the importance of the finance sector, and the securities industry, in particular, arises mainly from its role in generating income. The figure below shows that the four segments making up the finance sector accounted for about 30 percent of total city earnings. And the securities industry’s share of total income is on the order of 20 percent–one in every five dollars of income earned in the city. The annual average salary in the industry is currently about $375,000.

The figure also highlights the cyclical variability in the income share, a result of the importance of the annual performance-driven bonus payments made in the industry. A recent report on the securities industry pointed to this variability by showing that the cash bonus pool in 2006 was almost $35 billion and the average annual bonus reach $190,000; in 2008, the cash bonus pool had declined to $17 billion and the average annual bonus was just over $100,000. This variability is linked to the importance of the industry in the city, in fact, since the mid-1960s through the recent financial crisis, the ups and downs in total employment in the city have been led by the ups and downs in employment in the securities industry.

Forecasts show job growth in the securities industry slowing moderately to about 0.5 percent annually over the next several years, and wage growth slowing to about 1.4 percent. The outlook also has a number of associated risks that potentially weigh heavily on the performance of the sector and, as a result, the city’s economy. Two factors are related to the nature of the activities carried out by financial firms. One is the new regulatory environment that followed the financial crisis in 2008, particularly the changes to the allowable investment activities under the Dodd-Frank Act (Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act). These changes are being implemented even as there are suggestions that a number of the Act’s provisions might be softened. Any new legislation would carry implications for the activities, employment, and profitability in the sector. A second is the link of the performance of the sector to overall macroeconomic conditions. A recent report points out that the major income-generating activities in financial firms in New York City are linked to Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), mergers and acquisitions (M&As), and asset management. A slowing economy or significantly tightened financial environment could limit these kinds of activities.

Another risk factor is the need for ongoing efforts to keep New York City as an attractive location for major financial firms. Several states, including California, Texas, New York and Florida, have a large financial sector whose growth in the past five years has matched or exceeded that of New York City. These new clusters could be attractive to New York City or other financial firms seeking lower labor and land costs. Moreover, the city has faced a number of challenges over the past twenty years, such as the 9/11 attack and Superstorm Sandy. These events point to a need for continual monitoring of conditions that influence how financial firms think about locating and growing their business in New York City.