Joseph van der Naald

August 25, 2021

A great deal of attention has been paid recently to increasing job counts and declining unemployment claims. The Department of Labor’s August 6 news release indicated that July witnessed the single largest one-month period of employment growth (943,000 new jobs) since the late summer of 2020. The Department separately recorded 360,000 new unemployment claims during the week of July 10, which was the lowest number of such claims filed since March 14; however, the number of weekly claims have since risen again.

While most of the discussion on labor markets is overwhelmingly focused on what is happening within industries (primarily leisure and hospitality and retail) in the private sector, a frequently neglected area of the labor market is employment in the public sector. In the oft-forgotten area of public sector employment, declines in sales, income, and property taxes, as well as far below average tourism receipts have led to lower-than-average government revenues that have yielded extended furloughs and layoffs.

In this post, the first in a series of two, we will focus on the state of public-sector employment in state and local governments since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. We will look at the varied performance of state and local government employment and show that while the beginnings of what appear to be a rocky rebound elsewhere in the labor market are certainly encouraging, as many economists and observers have rightly emphasized, public sector employment is lagging far behind. The second post will investigate further the question of what fuels the recovery of state and local public employment, and why it has initially been more sluggish than other sectors, with a closer look into sub-national finances.

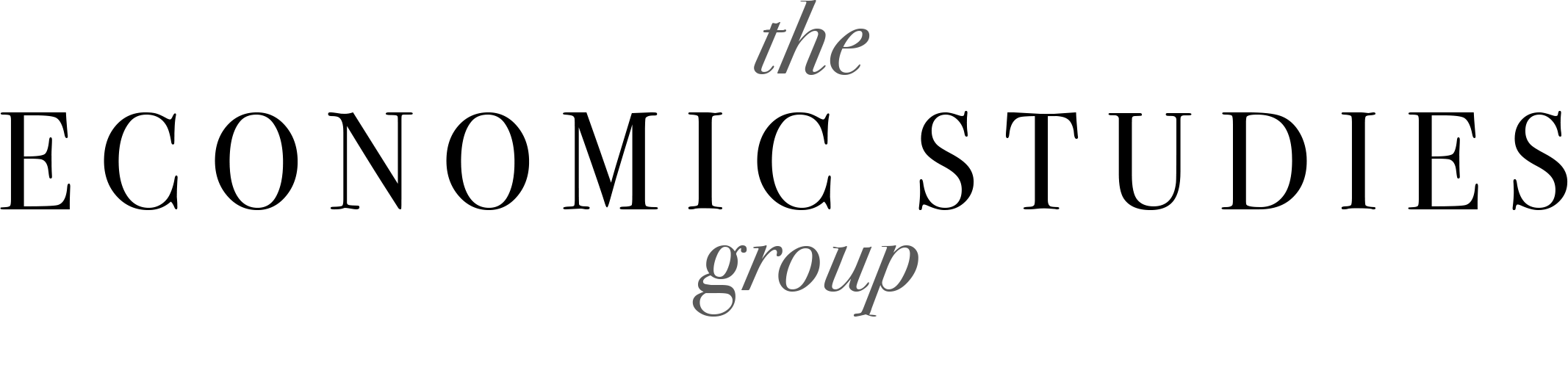

Figure 1. Total US State and Local Public-Sector Employment in Thousands, January 2000-July 2021

Source: National Current Employment Statistics, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Public-Sector Labor Market in Perspective

Public-sector jobs currently compose nearly 15 percent of all US non-farm employment, with a vast majority (87 percent) located in state and local government. As the chart in Figure 1 shows, between January and May 2020, the US economy shed around 1.5 million state and local public-sector jobs. By July of 2021 just a little over one-half of those jobs have returned. The decline in public-sector jobs in the wake of the COVID-19 recession has thus been both sharper and more severe than the loss of public-sector employment following the Great Recession. In the wake of the pandemic the sharp drop in public-sector employment initially set the number of state and local government jobs back to levels unseen since 2001. Though state and local public-sector jobs are returning at an increasing rate, employment in sub-national governmental sectors as of July 2021 is only just approaching its 2015 level.

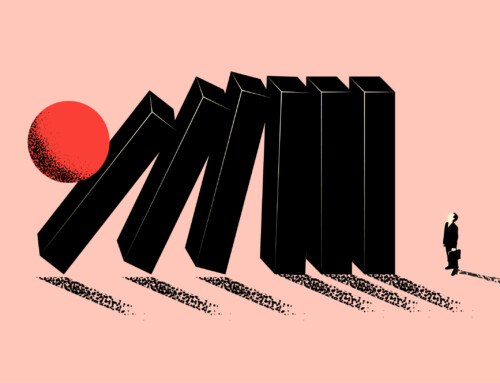

What is particularly worrisome about recessionary drops in public-sector employment are that they tend to be durable and slow to bounce back. Following the 2008 financial crisis, private-sector employment fell more sharply than all levels of public-sector employment. However, while the private sector reached its pre-recession levels by April 2014, state and local government employment would not reach December 2007 levels for another two and a half years ( Figure 2). This is especially the case for non-education state employment, which never recovered to its pre-recession levels. As of July 2021, both state and local government employment are rebounding, though this may be due in large part to the recovery of education jobs. When education employment is excluded from public-sector job figures, the employment recovery trend appears to be moving largely in the opposite direction.

Figure 2. Ratio of Pre-Great Recession Monthly Employment across Sectors, 2007-2021

Source: National Current Employment Statistics, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Source: National Current Employment Statistics, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

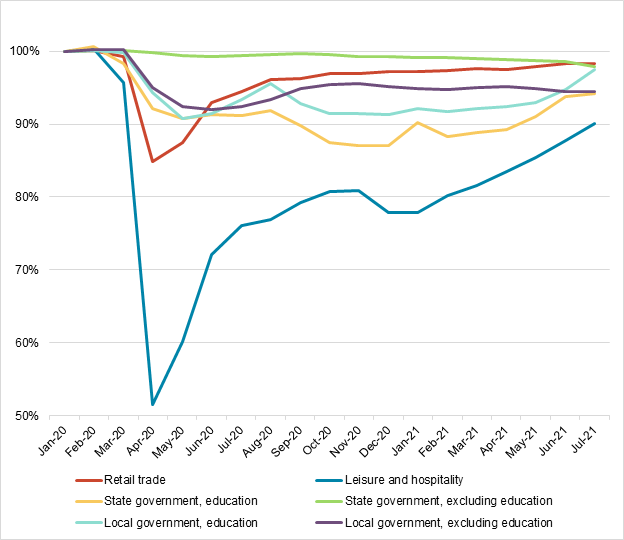

How does public-sector employment compare to two of the hardest-hit sectors of the labor market by COVID-19 pandemic, leisure and hospitality and retail trade? While all these sectors are experiencing some degree of job recovery, they differ in their rates of recovery. Unsurprisingly, the greatest decline in employment from January 2020 to July 2021 has been in leisure and hospitality, which remains approximately 10 percent below pre-pandemic levels ( Figure 3). Though also experiencing a significant initial dip in jobs, retail trade has fared better than state and local public-sector employment. Yet not all sub-sectors of state and local government employment have recovered equally. First, much of the pandemic decline in public-sector jobs has been in the education industry, particularly among non-instructional staff, food service, and transportation occupations. Auxiliary non-instructional education jobs will likely remain in an especially precarious position in the future, as they can become of the target of cuts when sub-national governments face potential persistent budget shortfalls. State public education institutions, largely in public colleges and universities, saw some of the most serious employment shortfalls. At their lowest point in December 2020, state education jobs had experienced a 13 percent decline as compared to pre-pandemic levels, though by July 2021 they have appeared to rebound to about 5 percent below their pre-pandemic levels. Yet, while state and local education employment appears to have begun a sharp rebound as of the spring of 2021, it is important to note that non-education local government jobs have not. Local government employment in particular has remained at around 5 percent below .

Figure 3. Percentage Change in Employment across Select Industries, January 2020 – July 2021

Source: National Current Employment Statistics, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: National Current Employment Statistics, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

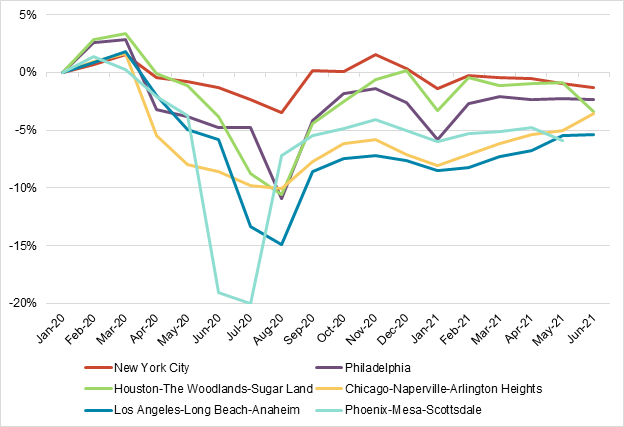

Given thatlocal government employment saw the most pronounced pandemic-related drops, it is worthwhile diving deeper to see how public-sector employment fared in individual cities and their outlying communities. Figure 4 presents changes in local government employment in the nation’s six largest cities and their metropolitan areas from January 2020 to June 2021 (except for Phoenix, whose data is available only through May). Unlike other data in this post, municipal-level local government employment data is not seasonally adjusted and is inclusive of workers in education and health services sectors employed by local governments. Additionally, some cities’ figures include local government workers in adjacent cities within the municipality’s metro area.

Nevertheless, the chart demonstrates that though all cities have been affected economically by the pandemic, their response in terms of varying employment differ markedly. The largest declines in public-sector employment have been in the southeast, in Phoenix (5.9 percent) and Los Angeles (5.4 percent) their adjacent urban areas. Cities where layoffs as of June have been most minimal include New York City (a 1.3 percent decline) and Philadelphia (a 2.3 percent decline). Among these six cities, New York City is an outlier in not only managing to keep employment relatively stable, but also to have grown the size of its public-sector labor force above pre-pandemic levels from September 2020 to January 2021.

Figure 4. Percentage Change in Local Government Employment, Six Largest Municipalities or Metropolitan Areas by Population, January 2020-June 2021

Source: National Current Employment Statistics, State and Metro Area, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: National Current Employment Statistics, State and Metro Area, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

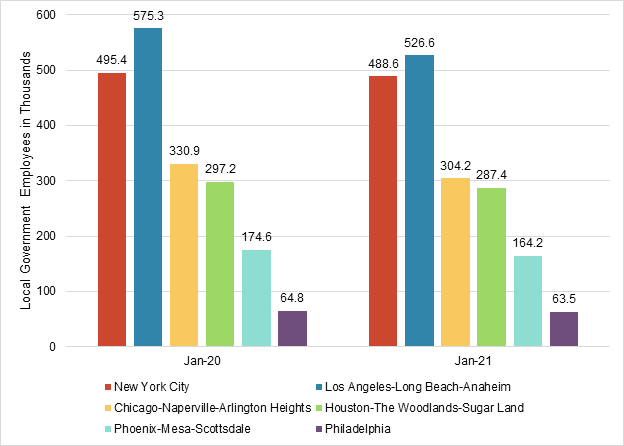

Because data on municipal employment is not seasonally adjusted and includes educational workers, the sharp drop in employment between June and August of 2020 visible in Figure 4 may be due, at least in part, to summer vacation at public schools. Thus, it is more illustrative to compare two months before and during the COVID-19 pandemic to examine the extent of the employment shortfall. Figure 5 compares the number of local government employees in the same six municipalities or metropolitan areas between Januarys in 2020 and 2021. By January 2021, Los Angeles was operating with nearly 50 thousand fewer government workers than it was a year prior, while Chicago and its outlying areas were operating with approximately 25 thousand fewer workers. Though in the seven months that have elapsed since January cities have continued to hire back furloughed and laid-off workers, as Figure 4 shows, the recovery process is far from complete.

Figure 5. Local Government Employment in Thousands, Six Largest Municipalities or Metropolitan Areas by Population, January 2020 and January 2021

Source: National Current Employment Statistics, State and Metro Area, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Source: National Current Employment Statistics, State and Metro Area, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Consequences of Public-Sector Employment Decline

The above-mentioned patterns of public-sector employment decline are troubling for least two reasons. First, public-sector layoffs, like unemployment elsewhere in labor market, drag down economic growth, as laid off workers lead to depressed consumer spending. Further, lagging government employment growth is indicative of austerity in state and local government spending, which has itself historically dragged out economic recoveries. Second, the public-sector disproportionately employs women and workers of color, so layoffs and furloughs in turn disproportionately affect these groups, making public-sector job declines an issue of racial and gender equity. A recent report by the New York Times shows that Black and Hispanic women experienced the greatest drops in employment and continue to be less likely to have returned to work as of April 2021. Given that Black women make up one out of every four public-sector workers, the slow recovery of government jobs has almost certainly contributed to persistent unemployment in this demographic group.

Importantly, the employment shortfalls documented above are linked directly to state and local budget revenues. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) provided state and local governments with much-needed aid to stem impending and future layoffs and furloughs. ARPA both provided greater sums of aid, as states received a total of $195 billion and local governments $130 billion, (as compared to the CARES Act’s $150 billion for all fifty states and 38 cities with populations greater than 500,000 people), and a greater degree of flexibility in how the federal aid can be spent, including use for the maintenance of government services and jobs.

The resources provided by ARPA can be used at least in part to stem some of the state and local government employment shortfalls documented in this post. Though relatively under-examined, the recovery of these public-sector jobs, as well as the public services that depend upon them, are an important component of reviving the economic health of United States as the nation works to ‘build back better.’