by Siokis Fotios

July 30, 2021

As we move away from the virulent pandemic, economic growth is gaining pace, while inflation is threatening to run rampant. With employment still 7.3 million jobs below its pre-pandemic level, how will the Fed respond? Nowadays no question is more vigorously debated than the inflation issue and in view of this discussion, the Federal Reserve System is reacting. The Fed, as a synchronous Janus—the two-faced, gatekeeping Roman God looking forward and backward, past and future and appeared to hold the keys of the opposite doors—is at the point of beginning a new chapter: looking both back and forth at the likelihood of a pandemic resurgence and in the near future, where mounting inflationary pressures could overheat the economy. The Fed is facing a crossroad, as the debate over the direction of the economy takes center stage. “Is the current monetary policy sustainable where the Fed has zero interest rates and buys securities worth $ 120 billion a month while there are strong growth prospects along with accelerating inflation?” In addition, there is the slower than expected return to employment, which complicates the situation even more.

The direction of the economy

In this rapidly changing economic environment, on Wednesday 16th June 2021, the Fed’s governor reiterated the decision of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) for an accommodative stance of monetary policy in promoting maximum employment and price stability, the so-called dual mandate. Target interest rates were kept at 0 to 0.25% levels, while asset purchases will continue, by at least $ 120 billion per month ($ 80 billion treasury securities plus $40 billion agency mortgage‑backed securities), until maximum employment and price stability goals are reached. The continuation of this program was deemed central to fostering smooth market functioning and to supporting the flow of credit to households and businesses.

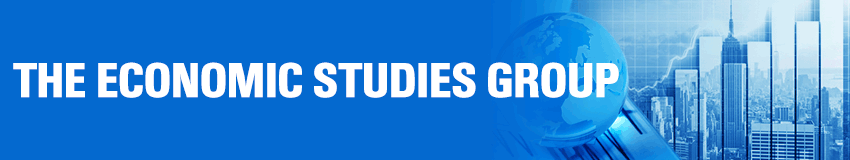

As for the forecast, the Fed revised the 2021 growth of the economy upwards from 6.5% in March to 7% in June and to 3.3% in 2022, while maintaining the unemployment rate forecast at 3.8% by the end of the year. In terms of the inflation rate, which experienced a huge upward momentum in the last couple of months, the forecast calls for a core inflation rate (which excludes volatile items such as energy and food) equal to 3% for 2021, before falling back to 2.1% in 2022 and 2023—a scenario consistent with a full recovery situation.

Figure 1. FOMC projections of the U.S. economy

What does recent inflation rate data mean to the Fed?

But in the post-pandemic era, strong economic recovery, backed by expansionary monetary and fiscal support sparked inflation to higher than anticipated levels, producing price pressures as excess demand for certain products outstripped supply.

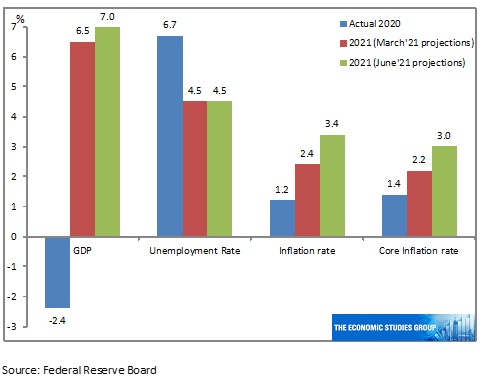

Based on the Personal Consumption Expenditure Price Index (PCE), the inflation rate increased in June to 4.0% year over year (and core PCE of 3.5%) compared with 3.9% a month earlier (core CPE of 3.4%), raising market concerns of an overheated economy (figure 2). Among the contrasting views of economists are those that claim the economy is producing above its capacity level “higher than potential GDP growth.” However the Fed’s policy makers are convincingly down-playing the rising concerns, supporting the narrative that the recent hike in the inflation rate is caused by transitory factors, like the recovery of oil prices, the bottlenecks in the supply chain, as businesses maintained low inventories due to the uncertainty of the pandemic and mainly to the so-called “base effect,” meaning that the price increases were compared with the corresponding period of the previous year, a very low inflation rate during the pandemic year. These distortions will last for few more months before inflation retreats—and in line with the Fed’s full recovery scenario—to around 2.1% in 2022. In that light, it is worth depicting an alternative measure of core inflation, the so-called “trimmed mean” inflation which captures most of the dynamics of inflation, is calculated by sorting in ascending order all price changes and then throwing out or trimming the most extreme observations (at both ends of the spectrum). In fig. 2 the trimmed mean follows a steady and flattened path.

Figure 2. The Inflation Rate.

The employment issue

In light of the dual mandate, there is a growing concern about the emerging employment situation. While unemployment is decreasing at a slower than expected rate, a growing number of job vacancies have been recorded, despite the rising demand for goods and services. The job vacancies have increased to 9.2 million in May, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, while the National Federation of Independent Business reported that 46% of small business owners in June were unable to fill job openings. This percentage is roughly in line with the 48% in May and greater than the 48-year average of 22%. Some of the main reasons for this distortion are: fears of the pandemic, parents locked in their houses mainly to assist their children as education was interrupted by the pandemic, high supplemental unemployment benefits and the “retirement boom” where more people than expected decided to exit the job market. Although this labor shortage is expected to sort itself out by the fall, as the supplemental unemployment benefits are set to expire in September and the percentage of vaccinated people increases, currently wage cost is pushed upward, putting pressure on the degree of competitiveness in small businesses, which admittedly were hurt the most during the pandemic.

Decoding the tone of the Federal Open market Committee, FOMC, and market reaction

The Fed frequently uses the forward guidance tool to communicate with the general public and align market expectations especially about how long it intends to keep the federal funds rate at current zero lower bound levels. In line with the approach adopted after 2011, and meticulously enhanced the level of transparency, the Fed is committed to maintaining an accommodative monetary policy until the economy achieves maximum employment, and core inflation is stabilized on average at around 2%. When can this goal be achieved? Based on recent data and according to their recent projections, the dual mandate could be met at the end of 2022. In this context, we could cautiously interpret the forecast exercise taken by the members of the FOMC, displayed in their “dot plot,” where each member of the committee is represented by a dot, two thirds of the 18 members are now projecting a series of two interest rate hikes within 2023, whereas a few months earlier the majority opinion signaled no liftoff in rates until 2024. Evidently the underlying dynamics of the economy and expectations of stronger recovery induced officials to rethink the future of the accommodative monetary policy and consequently adjust expectations as new data becomes available. Nevertheless, the Fed would move earlier to tapering its $120bn asset purchases, before any rate increase.

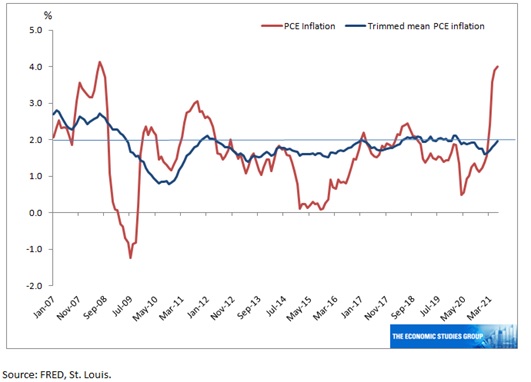

With the price increases and the Fed’s stated intentions, the markets reacted rigorously, sparking a sharp increase in the most sensitive to interest rate changes, i.e., to two- and five-year bond yields. Figure 3 depicts the yield curve (treasury instruments with different maturity) at different time intervals. The latest curve reported on July 28th is much steeper than the one reported on August 4th 2020 but less steep than the one after the announcement, meaning that the inflation worries were eased. Please note that an upward yield curve means that the market is expecting higher economic growth and higher inflation.

Figure 3. The evolution of the U.S. yield curve

Asset prices

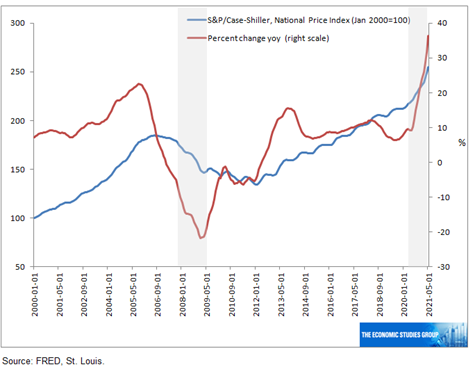

A critical issue that raises concerns in the Central Bank is the continuation of the strong and rapid pace in housing prices. Federal House Finance Agency indicates that the index for May 2021 increased by 18.0% on a yearly basis. By now, the index has far exceeded its peak, which occurred just before the eruption of the Great Recession. Factors such as the build-up of savings during the pandemic year, the very low mortgage rates, and the vast increase in other asset prices, like stocks, along with the limited supply of houses have bolstered the demand for housing. Many have articulated their concerns of a nascent bubble in the housing market, a situation that has occurred multiple times in the past with devastating results.

Figure 4. Housing Price Index

Conclusion

The recent decision by the Fed to boost the cycle by keeping its accommodative policy could be well justified, as risks from the pandemic are still high, while the number of unemployed people persistently remains above the pre-pandemic level. On the other hand, the strong recovery has boosted inflation to exorbitant “temporary” levels. Under the new monetary-policy framework adopted in August 2020, the Fed will wait for an interest rate hike until inflation and employment hit its dual mandate. But the problem with targeting average inflation rate is that nobody still has a clear understanding of how much inflation can be tolerated above the target, in order to make up for past shortfalls. This ambiguity, together with the transitory labor market rigidities could generate higher levels of uncertainty and confusion in the financial markets.