Fadime Demiralp and James Orr

October 31, 2020

Deep declines in employment across New York resulted from the efforts to contain the COVID-19 outbreak. Where does the economy stand? What factors will affect the recovery? We address these questions in this post. In March New York declared a state of emergency, public schools were closed, and an executive order was issued requiring residents to stay-at-home and all non-essential businesses to shut down. Containment efforts in states across the nation led to deep declines in aggregate economic activity. In New York, a phased reopening of economic activities got underway in May and currently the state’s economy is largely reopened, though with some important exceptions. A smooth process of recovery would generally have minimal new virus-related disruptions, employment returning to its pre-COVID-19 level, a so-called V-shaped recovery, and no spillovers that create longer-term negative economic impacts. In New York, employment has turned around and is well off its March/April lows, but recent job gains have slowed. Next, we use trends in employment to describe where the New York economy is in the recovery process and then outline the factors that might have an impact on the recovery.

New York hit hard by the COVID-19 crisis

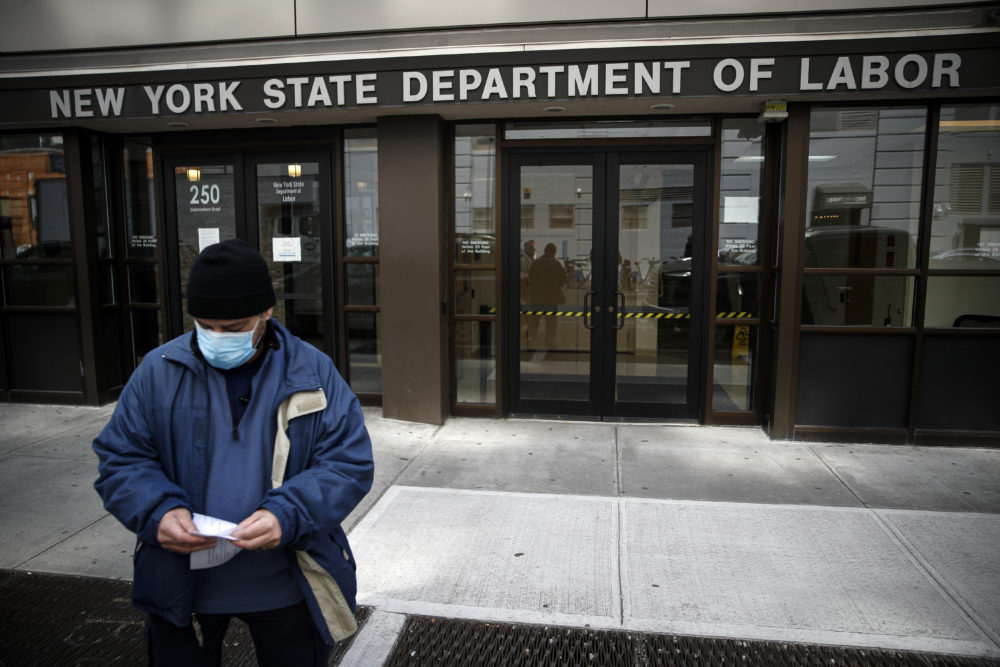

After the first reported COVID-19 case in late February, New York saw daily new cases rise to as much as 10,000 in mid-April before stabilizing at about 600 by mid-June. The pattern reflects the timing of new cases in New York City.

September saw the start of a rise in the number of daily new cases and localized clusters in the city, though the number of new cases is well below those of the Spring. Within New York City, the cases were relatively concentrated in areas with large household sizes and lower incomes, and the highest rate of new cases was among those aged 75 years and older. Deaths from the virus were concentrated in areas with large Black and Latino populations, as well as among the elderly; over 32,000 state residents and more than 23,000 city residents to date have died.

The state’s executive order was essentially a lockdown that, together with precautions by individuals to avoid the risk of contagion, resulted in a huge decline in economic activity in New York State and New York City. Early indications of the magnitude of the downturn came from March business surveys and the massive filings of initial claims for unemployment insurance. The impact was then reflected in job counts. The monthly index of employment shows huge declines in March and April in New York State, New York City and the nation: Employment in New York City fell by 944,000, or 20% of total city jobs, statewide by 1.945 million, also roughly 20% of the state total, and nationally by 22 million, about 15%.

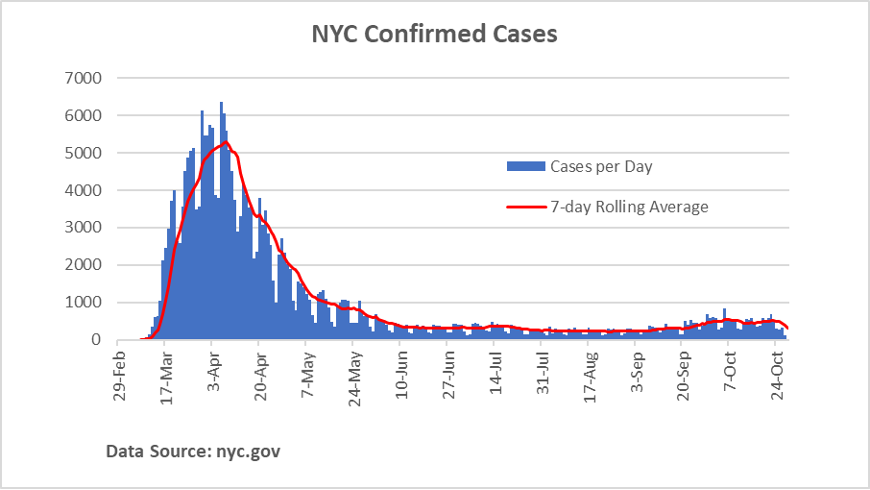

Unemployment rates also rose dramatically, rising from around 4% just prior to the crisis and peaking around 16% nationally and in New York State and over 20% in New York City.

Some of the hardest-hit industries in New York City were, predictably, those considered non-essential, affected by travel restrictions, and where face-to-face transactions are the norm, including hotels and restaurants, retail, segments of healthcare and social assistance, personal services, building services and transportation and warehousing. All non-essential construction projects were halted. Industries where office work was more typical were able to avoid major losses by having their workers work-at-home, including the information, finance and professional and technical services industries.

Signals from the real estate market reflect the recent weakness. In the residential market in the city, and Manhattan in particular, school closings, social distancing and work-from-home orders were associated with a sudden outmigration. It is not clear how permanent this is, but more mobile, higher-income residents appear to be those most likely to be moving; lower-income residents who have lost their jobs may have difficulties paying their rent. The market now has a rising rental inventory, more than double that of last summer and, in Manhattan, rents are down roughly 8% from a year ago. The commercial market is also weak: New leases in Manhattan were reported to be down more than 60% in August from last year’s monthly average, office rents are down, and sub-letting of space is on the rise. Bucking this trend is the ongoing purchases and leases of significant amounts of office space by major high-tech companies, suggesting they continue to pursue their long-term expansion plans in the city.

The COVID-19-related weakness in the state and city was compounded by the dampening effect of efforts throughout the country to address the rising number of new virus cases. In fact, the national economy was shown to have entered a recession in February. The national scope of the decline gave the impetus for broad monetary and fiscal programs to mitigate economic hardships for workers, businesses and state and local governments, and to maintain smooth functioning of financial markets. Congress is currently debating additional fiscal support.

Where does the economic recovery in New York City stand?

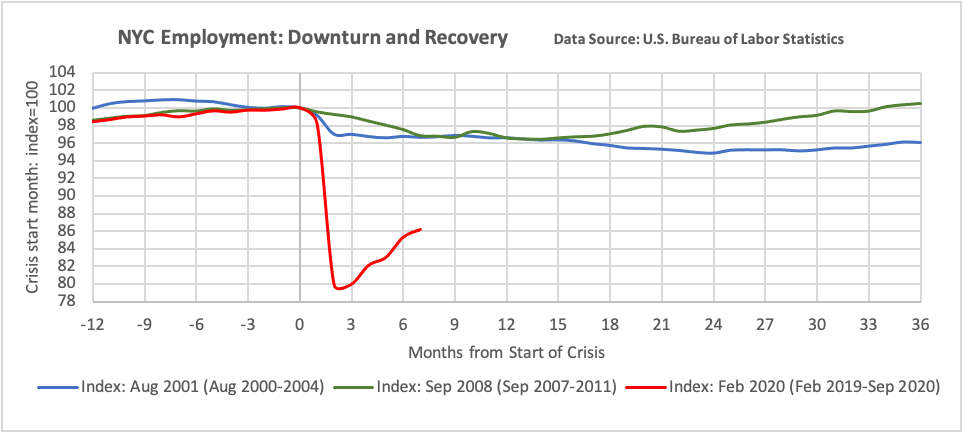

The phased reopening has been underway since the stay-at-home order ended on May 28. In New York City, ongoing social distancing practices still restrict some consumer activities and tourists and most office workers have yet to return. Focusing on employment, the recent decline was more than four time larger than in either the prior two downturns—that following the 9/11 attack in 2001 or the financial crisis that began in 2007.

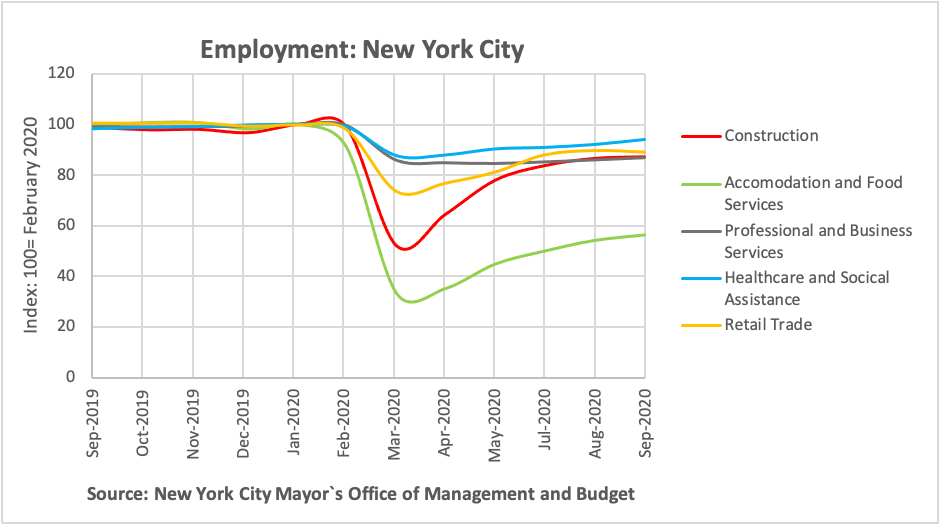

The developing V-shape pattern of employment recovery in the first seven months since the crisis started shows a bounce off the bottom and contrasts with the more gradual upturns in the two earlier cycles. The shape has flattened out a bit in the past two months, however, and there is now a fair amount of variation in employment recovery across industries.

Looking at five affected industries, employment in the healthcare and social assistance sector had a relatively small percent decline but has plateaued about 6% below its pre-COVID-19 level. The huge size of the sector means jobs are down about 45,000. The professional and business services sector also had a relatively modest percent decline, an important component related to services to buildings, and employment has been slow to recover. Retail tradeemployment had a much larger percent decline, including losses in clothing and department stores. The industry is still 10% below its pre-COVID-19 level.

Construction jobs had a large decline and a fairly strong bounce, characteristic of a V-shaped recovery, and has levelled off about 10% below pre-COVID-19 levels. Employment in the accommodation and food service sector was extremely hard hit, falling about 70%, or 250,000 jobs, before beginning to recover. A full return to business in this sector will likely require eliminating remaining restrictions on bars and restaurants and the return of customers in the varied base that it serves—residents, office workers, domestic and international tourists and business travelers–who will all need to feel much more comfortable in an environment based on individual contact. Although job gains there continue, the industry is still more 40% below its pre-COVID-19 level.

Looking ahead

The New York employment figures have clearly been moving in the right direction but the pace of recovery has slowed after the bounce off the March/April lows. However, initial claims for unemployment insurance in recent weeks are down and do not indicate a surge in job losses in either New York State or New York City. For New York City, forecasts have jobs down significantly from pre-COVID-19 levels this year though the pickup that began in May is expected to continue in 2021. The range of job forecasts is wide, and numerous risks remain. Local risks include a pickup in residential outmigration flows, or decisions by outmigrants not to return, and the reconfiguration of office work in a way that keeps significant numbers of workers at home or otherwise outside the city. Roughly 10% of office workers to date have returned. For governments, potential revenue shortfalls for both the state and city that lead to cutbacks in spending and services could weigh down economic activity. A follow-up federal fiscal package could address budgetary aid for state and local governments. Nationally, GDP is expected to grow in the second half of 2020 and into 2021, and should help support local industries—professional services, manufacturing, finance—that serve broader domestic markets. International travel and tourism are already highly constrained and the timing of a pickup here remains uncertain.

The full return to pre-COVID-19 levels of employment, or essentially a return to the trend of residents, consumers and businesses desiring proximity and feeling the traditional pull of the city, will be greatly supported by the development of a vaccine for the virus that reduces the need for social distancing and make shoppers, transit riders, tourists and office workers more comfortable being in the city.