Fotis Siokis

September 30, 2020

Introduction

With an enlarged balance sheet, what is the new operating regime of the Fed (or how does it conduct monetary policy) and what are its options? In this second post we address these questions. In Part 1 we discussed the action taken by the Fed to limit the economic damage from the pandemic and stabilize the highly volatile financial markets. We showed how in early March, the Fed first reduced the federal funds target rate to near zero levels. Then, moving beyond the conventional monetary policy tools, the Fed introduced an aggressive quantitative easing plan, purchasing unlimited amounts of longer-term assets ( U.S. Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities) and utilizing a variety of liquidity facilities. The aggressive response to the coronavirus crisis caused an enormous expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet, well above the elevated levels of the Great Recession. The superabundance of reserve balances held by banks at the Fed is attributed predominantly to the vast preponderance of excess reserves.

How does the excess liquidity environment affect monetary policy and why? The Federal Funds Rate and the Floor System

Historically, banks used to hold a minimum amount of excess reserves in the Fed just to meet transaction obligations. With limited excess reserves, the Fed could easily use the interest rate policy and, by conducting open market operations, steer the target of the federal funds rate. However, the dramatic increase of banks reserves held at the Fed impaired the mechanism of influencing the federal funds target rate. This is because the Fed could no longer rely on small changes in the supply of aggregate reserves to adjust the level of the federal funds rate. This outcome along with the authorization of the Fed to pay interest on banks reserves, under the Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act of 2006, signaled the beginning of a new policy regime. The Interest on Excess Reserves assumed a very powerful key role, in terms of “navigating” the federal funds rate and consequently the whole spectrum of short-term interest rates.

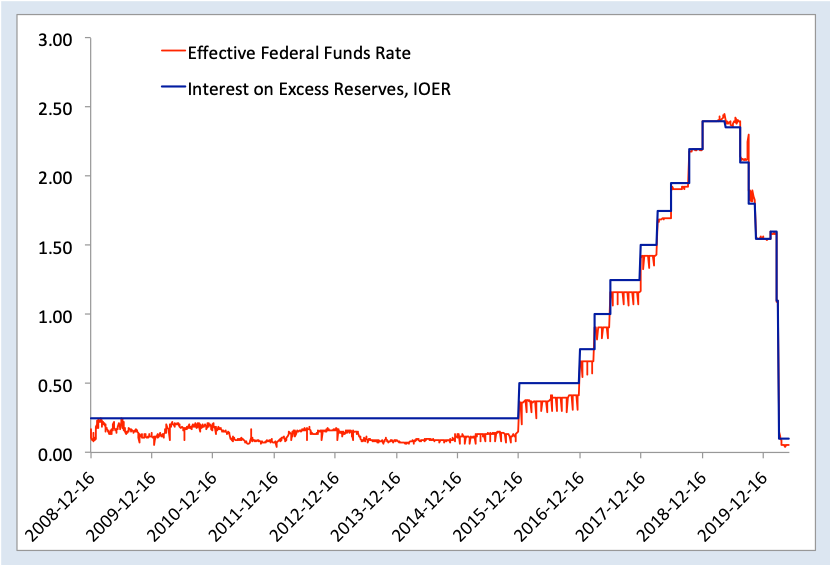

The interest on excess reserves as an administered rate sets the “floor” for the federal funds rate, below which banks have no incentive to lend to other banks. Although the two move closely together, a fed funds rate drifting far below the interest on excess reserves triggers arbitrage actions, in which banks borrow at the lower fed fund rate and deposit it as reserves and thus earn the higher interest on reserves. As can be seen in Figure 1, the fed funds rate is trading below interest rate on reserves since other institutions such as government-sponsored enterprises that have deposits at the Fed without earning interest on reserves, transact with other depository institutions and other institutions at the fed funds rate.

In addition, allowing other non-depository institutions, such as money–market funds or broker-dealers, to deposit funds for very short periods with the Fed, these funds earn a fixed interest rate less than the interest rate on reserves , called the overnight reverse repurchase program. With this program on board, the Fed complements the interest rate on excess reserves facility and increases the control over the fed funds target rate. The two interest rates serve as the upper and lower limits of the fed funds target range.

Figure 1. The evolution of interest on excess reserve and the federal funds rate

Source: FRED, Federal Reserve in St. Louis

In addition to the control of the interest rates, the Fed oversees a wider set of organizations (both the regulated and the shadow banking systems), and it can mitigate the economic incentives especially by depository institutions to engage in usurping excessive amounts of maturity transformation to finance long-term lending with short-term borrowing.

The expanding role of the Fed may lead to difficulties ahead

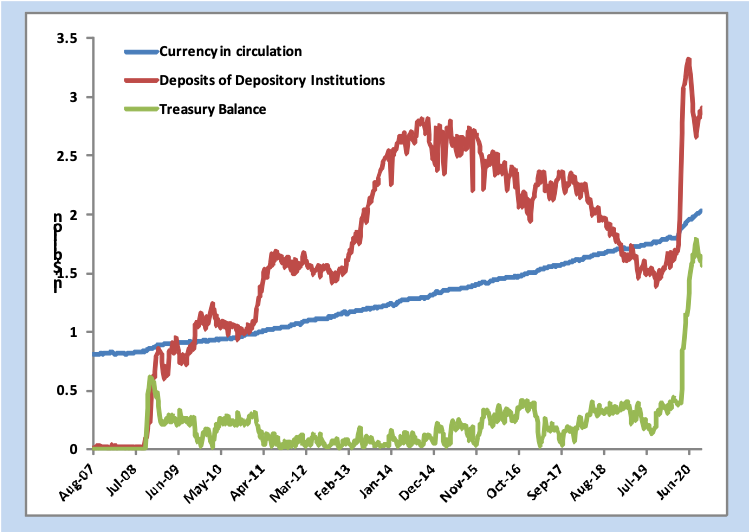

Inevitably, the Fed operates in an enduring environment of enlarged balance sheets. Judged by historical standards, the advent of an enlarged balance sheet is probably here to stay. With successive quantitative easing measures starting from the Great Recession and onwards, excess reserves have grown enormously. Particularly from September 2012, and due to signs of weaker than expected labor market conditions, the Federal Open Market Committee began a third round of large-scale asset purchases (Quantitative Easing, QE3), equal to $ 85 billion per month, which later decreased to $ 75 billion per month. As a result of QE3, depository institutions reserves increased dramatically (Figure 2, period 2012-2015), since banks receive cash in the form of reserves in exchange for their Treasury securities.

Figure2. Currency in circulation and Banks’ Deposits

Attempts to decrease asset holdings and consequently the reserves could be very challenging by causing disruptions in monetary policy and an arrhythmia in financial market functioning. Consider for example the incident in mid-September 2019 in which a reduction of the balance sheet was in progress, by means of not reinvesting the proceeds of bonds that were maturing, a process called normalization policy. It proved quite difficult to achieve the required federal funds target rate without the continuous interventions of the open market Fed’s desk. To assure markets that the system had ample supply of reserves, the desk had to conduct term and overnight repurchase agreement operations in the amount of $60 billion in short-term Treasury securities per month and for at least six months.

Yet, some of the liquidity facilities introduced by the Fed, such as the program of buying investment-grade corporate debt from primary and secondary markets, could open the Pandora’s box. Not only the Fed assumes credit risk, which could be quite worrisome and constrain the efficacy of monetary policy, but also the employment of multidimensional tools could blur the boundary between monetary and fiscal policy, threatening the Fed’s policy independence.

The issue of independence deserves broader consideration because, under the terms of an enlarged balance sheet, the Fed in the role of a multipurpose vehicle could create the conditions for off-budget fiscal policy and credit allocation attempts.Political interference as it happened in the past and particularly in 2015, where the Fed funded a transportation bill under congressional mandate, could limit the Fed’s independence which is widely viewed as an important pillar of sound monetary policy.

Discussion

Increased purchases of longer-term assets illustrate the fact that central banks increasingly rely on balance sheet policy rather than the traditional interest rate policy. This reliance is likely due to the fact that the supply of reserves is greater than the demand, creating the need to establish new levels of interest on excess reserves as the floor and the ON RRP as a subfloor. Therefore, the interest on excess reserves as the new instrument of monetary policy is complementary to maintain a large balance sheet and offers an opportunity to improve financial stability.

Also, worth noting that recently Chair Jerome Powell announced a change in the inflation targeting policy, shifting from a 2% target to “a flexible form of average inflation targeting” strategy. The new framework indicates that the Fed will now allow inflation to overshoot 2% temporarily-with the average to be 2%- to compensate for times when the rate falls for quite some time, as it does right now, below the 2.0% target. As it stands, the layout of the new average inflation targeting strategy is not so explicit. The Fed should provide adequate details as to how it will calculate the average inflation, and it should provide some form of forward guidance regarding the time period that inflation remain above the 2% target, or it will be tied to the state of the economy.

In principle this new framework is constructed to (i) to create more inflation, although the Fed’s main challenge is to demonstrate how this can be achieved, after years of undershooting 2%, (ii) give some space to monetary policy and (iii) contain inflation expectations close to 2%. Hence, for those reasons the new inflation targeting framework points to a monetary policy where short term interest rates will stay close to zero lower bound area for at least the next couple of years, even if the unemployment rate reaches low levels.

Lastly, the regime in setting up interest rates is analogous to that of other central banks like the European Central Bank or the Bank of Japan. The major difference is that, with zero lower-bound interest rates, these two central banks have operated for quite some time in an environment of negative banks’ deposit interest rates. Could the fed contemplate a similar financial environment?