The United States, Mexico, and NAFTA

The Economic Studies Group

Jun 28, 2017

The terms of current and proposed U.S. trade agreements are getting renewed attention as to their impacts on the U.S. economy and workforce. Recently, U.S. trade with Mexico has become a particular focus for reconsideration as trade between the two countries has grown remarkably since the 1994 passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and reaching agreement on the benefits and costs of NAFTA has been hard.

Most of the recent discussion centered around the impact of trade on the loss of U.S. jobs in manufacturing. While the factors causing this outcome are diverse and not limited to NAFTA, ranging from globalization and automation to monetary and fiscal policies, the argument leaves out the benefits that are derived from trade with Mexico Several features of U.S.-Mexico trade flows were noted in a recent analysis of the U.S-Mexico trade relationship by the Trade and NAFTA Office of the Ministry of the Economy of Mexico, and could warrant consideration in any review of NAFTA. In this post, we highlight four of the features of that analysis: the intra-industry nature of goods trade, the U.S. surplus in services trade, the specialization in agricultural trade and the geographic concentration of the importance of Mexico to state exports. Each of these presents an aspect of U.S.-Mexico trade that is related to the potential benefits and costs of a renegotiated agreement.

U.S. trade with Mexico has grown dramatically since the passage of NAFTA. The figure below shows roughly balanced trade in 1994 totaling $100 billion expanding to $525 billion by 2016 and with a bilateral deficit of about $63 billion. With $1.5 billion dollars in products traded bilaterally each day, Mexico has become the third largest partner and the second largest export market for the U.S., and the second largest supplier of imports.

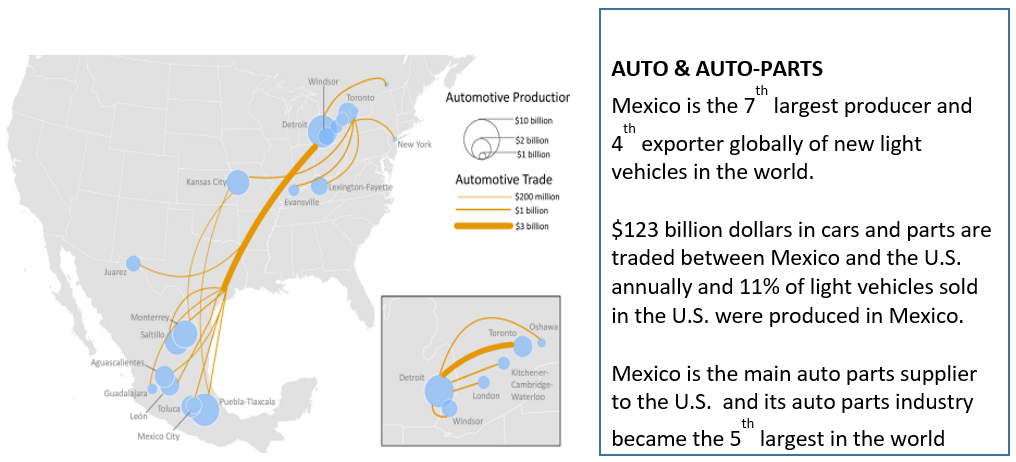

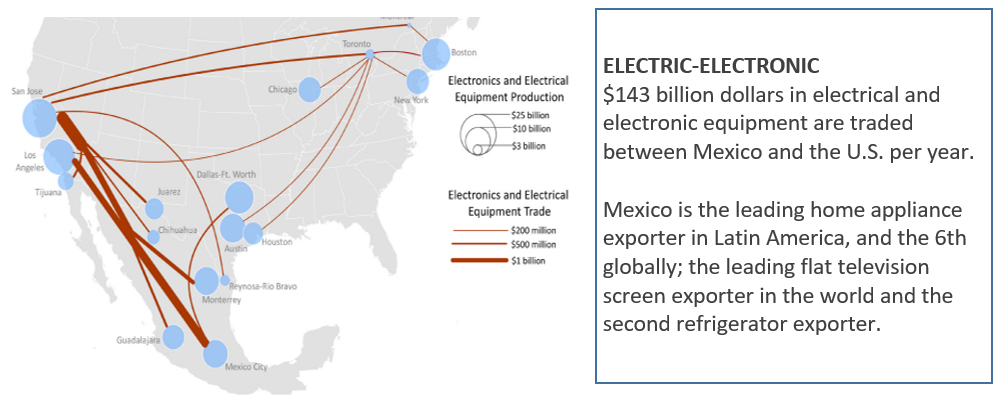

A closer look at the trade flows indicates that trade has strengthened supply chains in key industries, particularly autos and electronics.

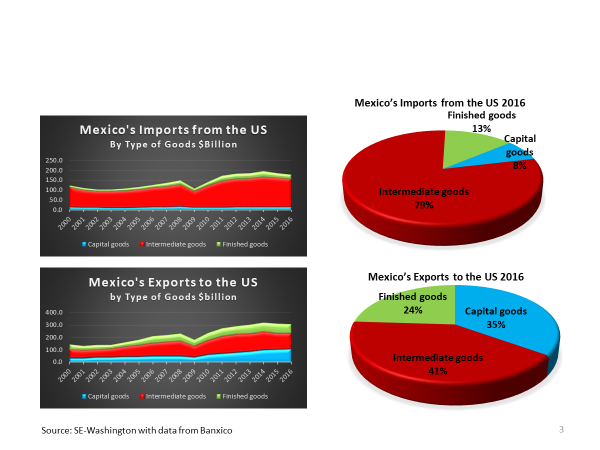

These intermediate goods also comprise a large share of Mexico’s exports to the U.S., though there is a larger component of finished goods. These bilateral trade flows further indicate that U.S.-Mexico trade reflects the expanding supply chain between manufacturers in the two countries.

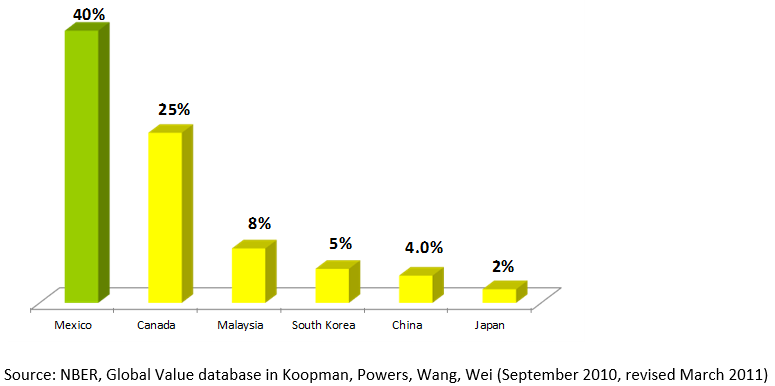

More generally, U.S, exports to Mexico consist largely of intermediate goods or products that are used as inputs into the manufacturers in the two countries. In fact, it has been estimated that there is 40 percent value added by U.S. producers in Mexico’s exports, a figure much larger than that for other suppliers.

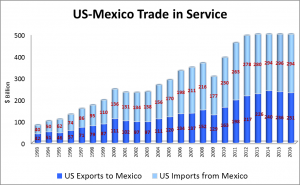

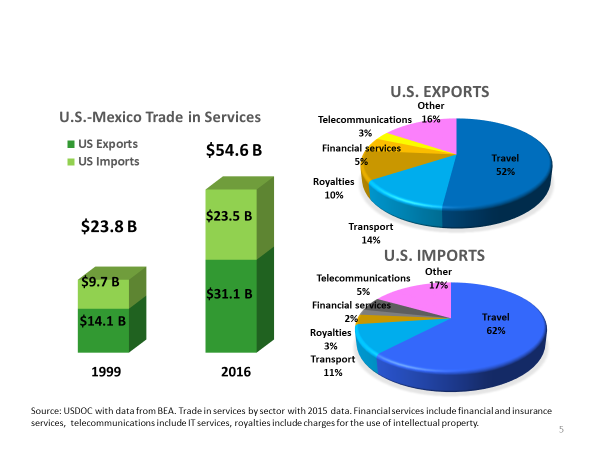

U.S. – Mexico trade in services has also expanded greatly since the 1990s. Much of that trade is in the area of travel and transportation, rough 65 to 70 percent, but there is also trade in telecommunications and financial services. And similar to overall U.S. trade flows, the U.S. maintains a surplus in services trade with Mexico.

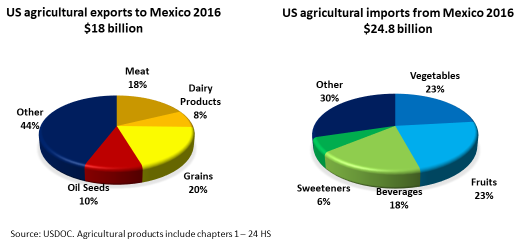

Trade in agricultural products between the two countries is also large, with the U.S. exporting about $18 billion worth of products to Mexico and importing almost $25 billion worth of products from Mexico annually. The composition of this trade reflects the resources of the two countries. A look at the 2016 trade figures below shows, U.S. exports consist of meats, dairy products, grains, and oilseeds while U.S. imports comprise a large amount of fruits, vegetables, and beverages.

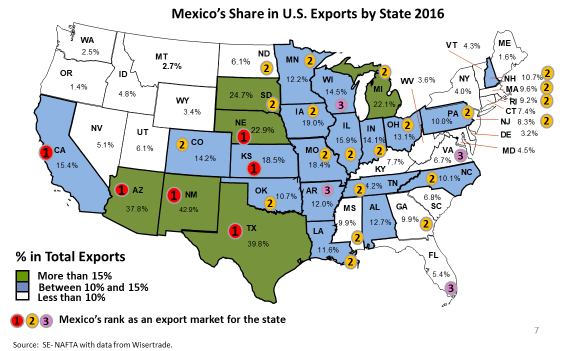

The concentration of U.S. goods exports to Mexico in autos, electronics, and other intermediate inputs together with these agricultural exports of U.S. staples suggests an uneven geographic pattern of the source of these exports. The figure below looks at states and shows that Mexico is an important export market for the four border states, and South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, and Kansas in the Midwest, and Michigan, and Mexico ranks among the second and third largest export markets for 21 additional states.

The data on trade flows between the U.S. and Mexico suggest that the economic relationship between the two countries has several specific features that should be considered in the discussion of a renegotiation of NAFTA. The evolution of goods trade into a large component that reflects supply chains within manufacturing firms and industries could be costly to break. The composition of trade in agricultural products and services actually suggests a more typical pattern of trade observed with other countries. So, it is really with regard to goods trade that negotiators need to bear in mind that the composition of trade flows reflects the evolution of intra-firm and inter-industry relationships that have developed over time.