Is the New York Economy Slowing Down?

James Orr

October 26, 2017

Recently-released employment figures show the number of jobs in New York State and New York City declined sharply in September: The state lost about 34,000 jobs and about two-thirds of the decline occurred in the city, suggesting a possible slowing of the robust employment picture seen downstate. This post examines these recent job numbers and to what extent there is a suggestion of a cooling off of job growth. It then looks at several services sectors that have been key drivers of job growth over the past year, including one sector–retail trade—where consumer buying trends have been linked to ongoing job losses nationally as well as in the state and city. Looking ahead, the administration’s recently released framework for federal tax reform proposes the elimination of the deductibility of state and local taxes. In light of the relatively large value of these deductions taken by New York residents, the post reviews the evidence regarding how this proposal could affect federal income taxes paid by New York residents.

Employment trends in New York City, the State and the Nation

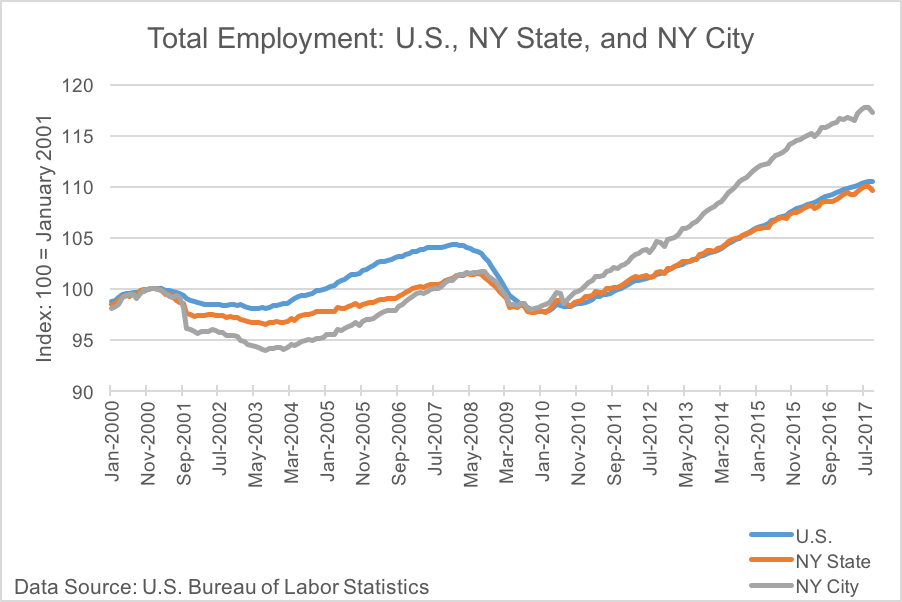

While the expansion of employment in New York City since the recovery began seven years ago has been remarkable, the preliminary September employment figures show a loss of almost 20,000 jobs. Although these estimates are subject to revision next month, declines of this magnitude on a monthly basis have been observed several times during the city’s employment recovery. The chart below shows the sharp and steady rise in employment in the city relative to both the state and the nation since the recovery of jobs began in 2010, and indicates the relative magnitude of the recent decline. In the city September’s losses were concentrated in the private sector and while steep, overall employment in the city in September is still up about 1.1 percent over September of last year. Comparisons of job growth with the nation this month are problematic, however, due to the hurricane-related distortions in the national payroll employment estimates.

Statewide, employment losses totaled about 34,000 though, like the city, overall employment in the state remained above its year-ago level by roughly 1.0 percent. The September declines in employment might have been hinted at in the August jobs report where the slowing pace of job growth nationally was also seen in both New York State and New York City. While the year-over-year growth rates held up, the month-over-month job growth rates in August were below the average monthly growth rates seen over the past year. In September, the decline in statewide employment was broad based across industries and, notably, declines occurred in the education and health sector which had been expanding throughout the downturn and recovery.

As discussed in a recent report, the areas outside of the city have not been showing the consistent strength in job growth that is seen in the city. Moreover, as pointed out in an earlier post, the city’s strong job growth in this recovery has been accompanied by strong population growth and there was not the sharp decline in the city’s labor force participation rate during that period that was seen nationally. Data for upcoming months will show whether the job losses seen in September are continuing and thus providing more evidence of a possible cooling off in growth in both the state and city.

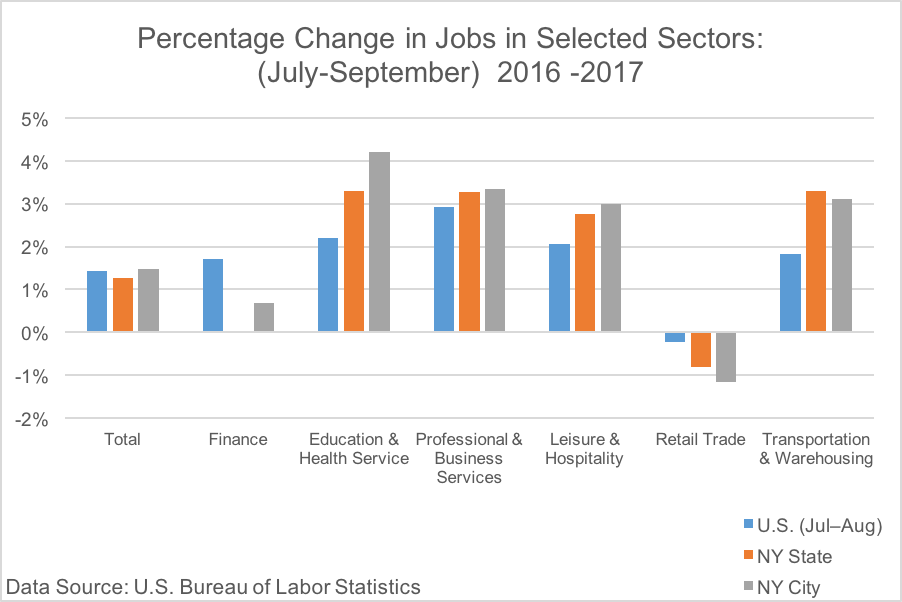

A look at the job growth rates by sector shows that over the past year, major services sectors—education and health services, professional and business services and leisure and hospitality—made strong contributions to the job growth rates in both the city and state. The relatively poorer performance of the finance and retail trade sectors is noteworthy. Employment in the finance sector has not been leading the recovery as in previous upturns and over the past year has seen only modest growth.

The decline in jobs in retail trade over the past year in the nationally and in New York State and New York City reflects, in part, the impact of the rise of online sales, or e-commerce, and the decline in sales in brick-and-mortar stores, particularly department stores, but also at stores selling electronics, sporting goods and clothing. A recent report shows that online shopping nationally now constitutes more than 10 percent of total retail sales. These shopping trends are increasingly supported by expanded personalized online marketing and rapid, often overnight, product delivery.

Department stores are especially affected by online shopping. Spending at department stores in August of this year was essentially flat from last year and down about 15 percent over the past five years. In the city and state, employment at department stores was down roughly 2 percent over last year and contributed to the decline in retail trade employment. Unlike the nation and the state, however, jobs in New York City in clothing, food and health and personal care stores increased. Finally, two recent reports suggest that the decline in jobs in brick-and-mortar retail stores are to some extent being offset by gains in the warehousing and transporting of goods. Jobs in this sector are up sharply in the nation, New York State and New York City, though these gains are not unambiguously related to the increase in online shopping.

Proposed elimination of state and local tax deductibility

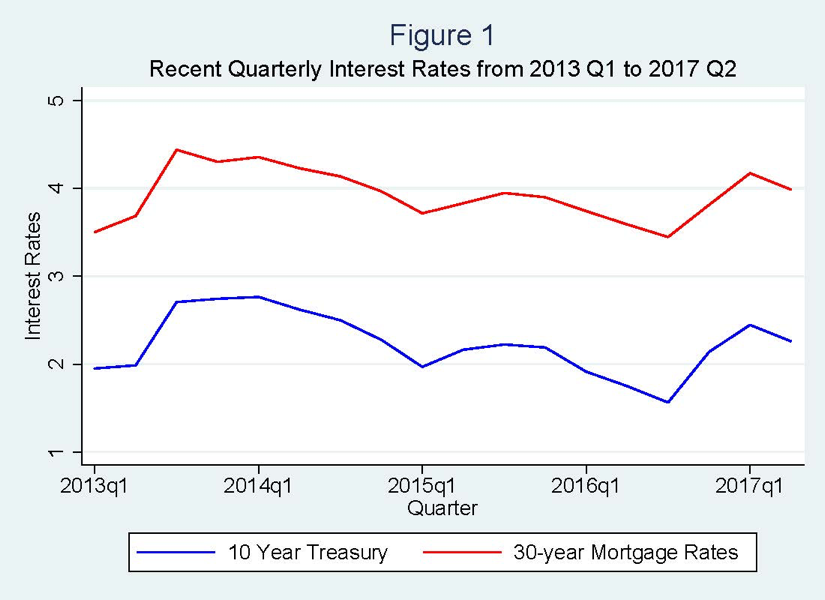

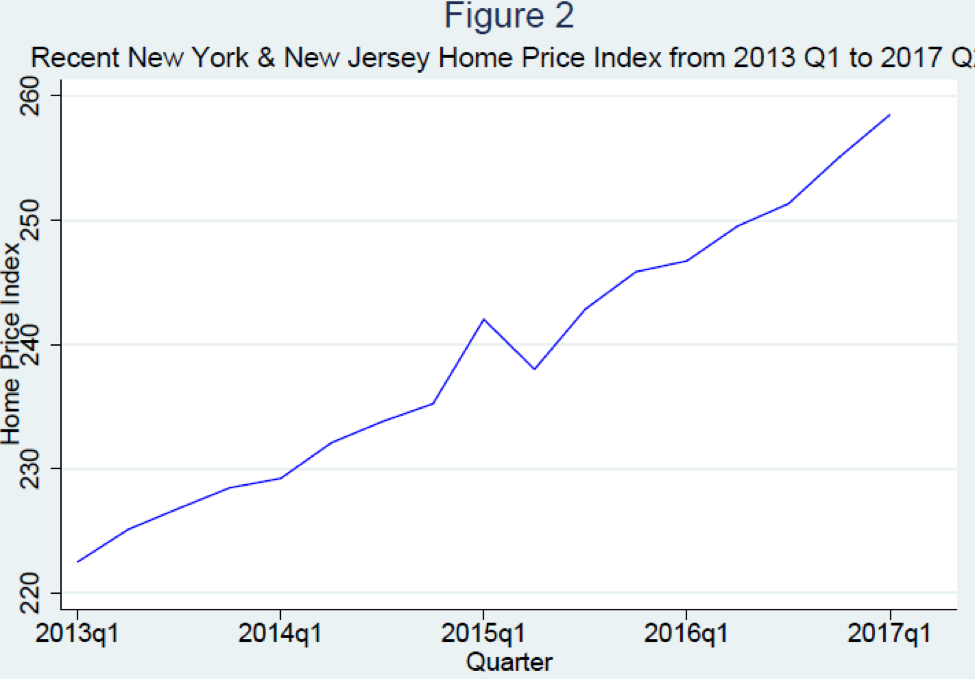

The administration’s recently-released framework for federal tax reform proposes eliminating all itemized deductions for individuals other than for mortgage interest and charitable contributions. The proposed elimination of one such deduction, that for state and local tax payments, could have consequences for New Yorkers and the state’s economy. Under current law, individuals can take a deduction against their income for state and local taxes paid. These taxes consist of real estate taxes as well as either non-business income or sales taxes.

Estimating the amount of additional federal taxes that will be paid by New Yorkers as a result of eliminating the deduction is complicated because the framework proposes a number of other changes that will affect individual tax payments. These include changes to the value of the standard deduction and personal exemptions, the income limits applicable to the new tax brackets, and the elimination of the AMT, a parallel tax system for relatively high earners that does not allow these state and local tax deductions. A report from the Tax Policy Center estimates that the elimination of the state and local tax deduction alone would raise federal tax payments for individual New Yorkers who take the deduction by an average of $4000. An estimate by the New York City Comptroller’s office shows that the elimination of the tax deduction would not just affect higher income earners but affect taxpayers across a range of incomes. While there are some efforts to estimate the impact of eliminating the deduction on New Yorkers within the context of the proposed framework, the net changes in federal tax liabilities and, ultimately, the impact on economic activity will depend on what other aspects of the framework are adopted.