Mark G. Sheppard

February 25, 2025

In October, prior to the election, The Economist, arguably the most popular economic weekly journal, published an article entitled “America’s economy is bigger and better than ever”, this basic sentiment of topline success was echoed by a number of institutions from the Federal Reserve to BlueChip, from the OECD to a survey of top economists, and more. There was broad agreement among economists that the economy was doing fairly well, which generally bodes well for a presidential re-election bid, however the incumbent party not only lost the election, but the incumbent president was pushed out of the general election over falling polling numbers, largely informed by rising economic discontent. The topline economic figures were somewhat at odds with how voters and consumers experienced the economy. Survey data showed affordability concerns, specifically the gap between wages and prices, were a top priority.

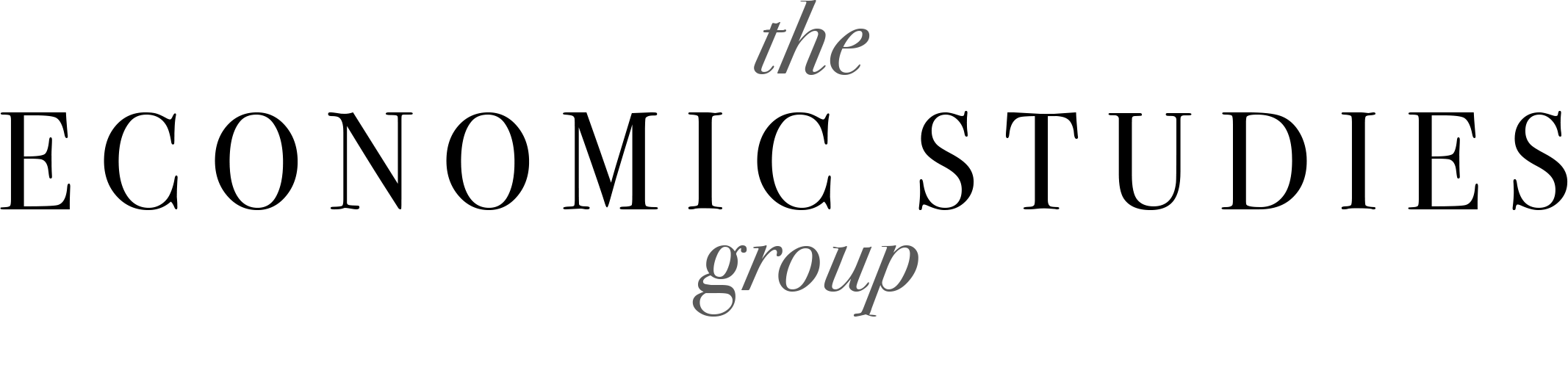

Economists, including almost all living Nobel laureates, broadly supported Kamala Harris in an election that Donald Trump won handedly. That academic support was largely informed by economic policy preferences, but also of a descriptive political model that simply undervalued how discontent voters were with the economy. In the lead up to the election, while affordability concerns remained paramount for many American voters, economists spent months praising topline figures such as GDP, unemployment, inflation, and other metrics. Election modelers discounted the degree to which the economic fundamentals would downweigh the polls, producing estimates that showed a much tighter race; And economists were reluctant to acknowledge the extent to which —and the parts of— the economy that would matter in the election.

Right before the election, noted political statistician Nate Silver sounded the alarm that concerns over the economy could be informative in the election, by posting preliminary regression results of inflation and a shift in the polls, which were pretty widely criticized by economists mostly on the grounds that the underlying methodology would otherwise fall below academic publishing standards. And while the economists were probably technically right in that pushback —so was the basic intuition in the regression. The economic fundamentals were deeply unfavorable for an incumbent re-election bid. Interestingly, calibrating the exact amount that the economy could and would politically matter has been done in the past, but election modelers seemed hesitant to include those parameters.

Election models rely primarily on polling aggregation, and while many models performed well enough, the main issue in the modeling was two-fold: firstly, polls were about as wrong as they normally are, and secondly, the economy mattered more than the models factored-in. For politicians, pollsters, and economists looking to make sense of this rightward shift, voters were fairly clear in communicating economic discontent. And though pollsters were basically right, political forecasters could have anticipated the shift if traditional economic indicators were built-in.

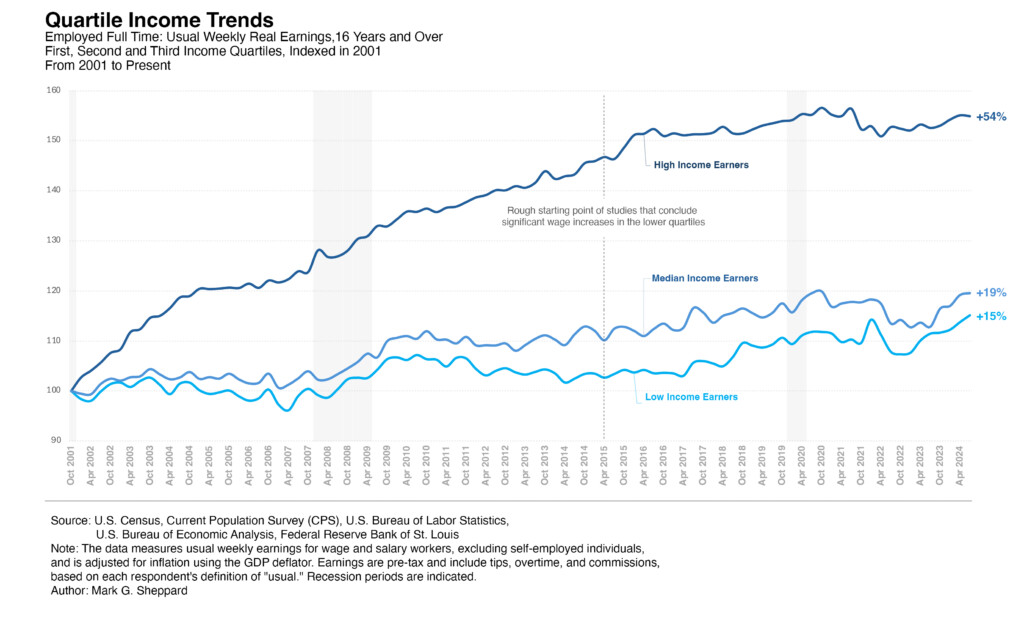

Though inflation received much of the consideration in the aftermath of the election, long-run wage trends are also poor, with almost half of Americans earn less than a livable wage. Collectively, rising cost and stagnate wages are the main components of the growing affordability crisis. Recent gains in wages have been highlighted by economists interested in supporting recent policy successes, but the long run trends are mostly flat, which matter more to voters. From the ballooning housing-to-income ratio to the rising credit card delinquency rates, there is simply no shortage of concerning indicators.

As the new administration begins its second term, inflation remains stubborn, consumer confidence remains troubled, and the underlying affordability issues will likely linger. Political strategists and pundits have been struggling to make sense of the rising non-white block of new conservative voters, but frustration with an unaffordable economy explains the diversity shift in the crosstabs, as inflation affects voters of all groups. However, issue polling and various statewide proposition results show most people broadly agree with the progressive policies that economists are endorsing, but voters are still clearly disagreeing with the economists on the state of the economy. Put simply, from the perspective of voters, an improving economy that is ‘technically better than peer countries’ is not a “good economy.” Looking ahead, political forecasters should remember that the economy matters in elections, and what matters most is not the aggregate statistics but rather how people experience the economy; Economists should learn this lesson too.

As the new administration begins its second term, inflation remains stubborn, consumer confidence remains troubled, and the underlying affordability issues will likely linger. Political strategists and pundits have been struggling to make sense of the rising non-white block of new conservative voters, but frustration with an unaffordable economy explains the diversity shift in the crosstabs, as inflation affects voters of all groups. However, issue polling and various statewide proposition results show most people broadly agree with the progressive policies that economists are endorsing, but voters are still clearly disagreeing with the economists on the state of the economy. Put simply, from the perspective of voters, an improving economy that is ‘technically better than peer countries’ is not a “good economy.” Looking ahead, political forecasters should remember that the economy matters in elections, and what matters most is not the aggregate statistics but rather how people experience the economy; Economists should learn this lesson too.