June 24, 2024

fsiokis (0)

Over the past forty years, the unique U.S. banking system has faced significant competitive challenges, in a rapidly changing technological environment, along with far-reaching regulatory reforms, ushering in an era of remarkable consolidation. In this post we outline the differences of the US Banking system compared to the other global banking systems, its transformation and how it evolved over the years.

The commercial banking system in the United States was distinct and complex when compared to the banking industry in many other industrialized countries. In one regard, it is distinguished by a fragmented system with a numerousness banking institutions; at its peak, in 1921, the United States had over 30,000 independent commercial banks. On the other hand, the hallmark of the US banking system is the so-called “dual banking system”, a co-existence of state and federal banking systems. The former was characterized by state chartering, established by state law and operates under state standards, while the latter was based on a federal bank charter established by federal law and oversights by a federal supervisor. The main reason for developing and maintaining such a system was the authority vested to the states to grant licenses and regulate the banking system. For most of the past years, the states perseveringly guarded this mandate and protected the instate banks from outside competition by prohibiting interstate and in some cases intrastate banking. Therefore, the exorbitant number of banks, with restricted authority to provide services in securities, insurance, and real estate-related financial service, were in essence one branch banks.

The decreasing number of banks

Historically, US banking regulations supported the existence of numerous small local/community independent banks. The vast majority of small banks were founded on the belief that they were essential to their community, farmers, and small companies, and that they could provide specialized and targeted goods to their customers, something larger banks could not. Despite the fact that most of the restrictions have been lifted on a continuous basis, since the 1980s, there are still over 4,100 insured commercial banks and over 580 insured savings institutions in existence in the United States. In contrast to the U.S. experience, most of the other countries tended to favor less but larger national institutions, like Canada’s where in 2023, had only 38 domestic banks, the Japanese economy with 163 banks (data 2019), while Germany has 261 commercial banks.

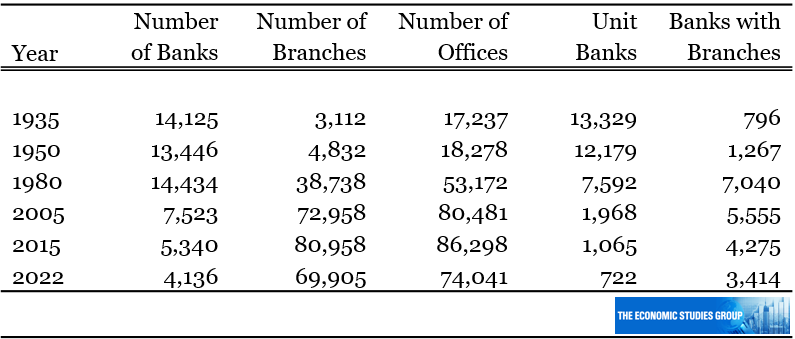

Table 1. Number of commercial banks in the United States.

Source: FDIC.

As shown in Table 1, the number of banks has decreased significantly since 1935, with unit banks reporting a 20fold drop. The opposite trend was observed in the number of branches.

Supervision

Similar to the duality concept, the banking system is supervised and protected by a numerous and intricate network of regulatory bodies. The primary players in the commercial banking system include national banks, state member banks, and state non-member banks as well as foreign banks that opened offices in the United States. In addition, there are other types of banks, such as savings banks and credit unions. Every bank is required to apply for a bank charter and is then governed by the chartering body. Most of the banks are subject to supervision by more than one regulatory body. If a bank is chartered on a state level then is supervised by the state authorities and if it is insured in terms of deposits (almost in all cases) is regulated by the Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC). In addition if this bank becomes member of the Federal Reserve System then the major supervising body is the Federal Reserve. This structure becomes even more complex for the bank and Financial Holding Companies (having subsidiaries) that are subject to another layer of regulation at the parent level. Therefore, the regulatory agencies that supervise and oversees the operations of the banking system have the authority to issue cease-and-desist orders, revoke membership and other divestiture or termination activities include: 1) The Federal Reserve System which is the major supervising agency for the banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System and for the bank and financial holding companies. 2). The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the oldest of the federal bank regulatory agencies. An independent bureau within the U.S. Department of the Treasury that charters, regulates, and supervises all national banks, federal savings associations, and branches and agencies of foreign banks. In 2009, the OCC absorbed the Office of the Thrift Supervision (OTT) that supervised Thrift Banks like the Savings &Loans Banks. 3. State banking agencies. The state banks along with foreign branches bank should comply with state laws. 4. Other major regulatory bodies including, the Security and Exchange Commission (regulates institutions that engage in security and investment related activities), the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council.

Regulatory reforms

The banking system had its most severe collapse during the Great Depression. Between 1929 and 1933, around 10,000 banks failed. Aside from the consequences of the Great Depression, the primary reason of bank failures was increased competition among banks, which caused the majority of them to take unnecessary risks in order to survive. The intense competitiveness caused by large commercial banks entering the investment banking industry compelled Congress to pass the Glass-Steagall Act (1933), which required the official separation of commercial and investment banking and effectively precluded banks from underwriting corporate securities.

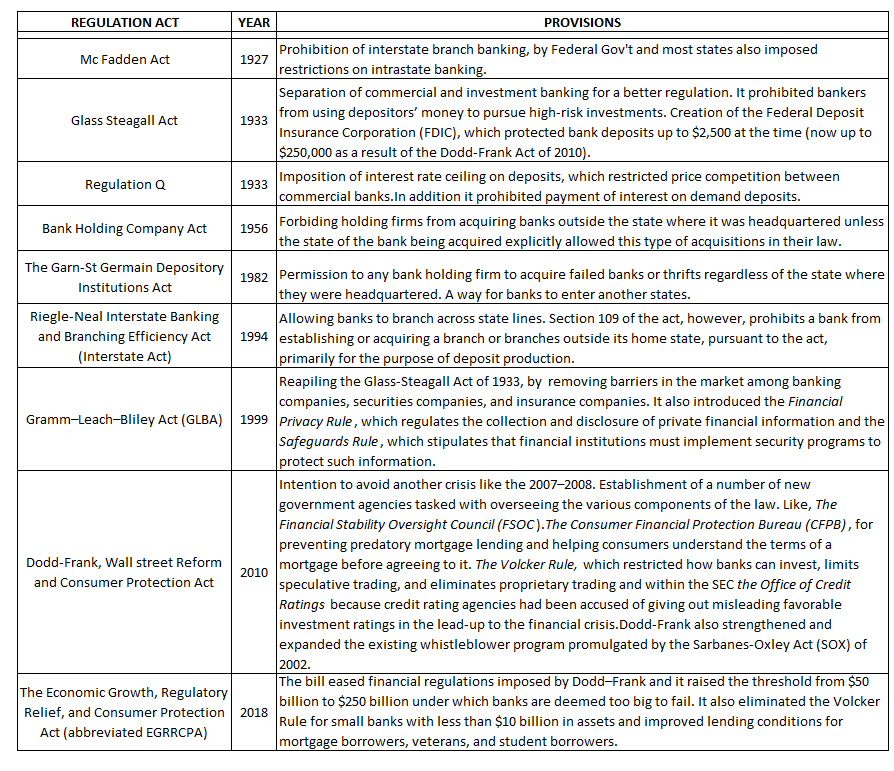

Table 2. Major Banking Regulations since 1927.

Source: fdic.gov/resources/regulations/important-banking-laws/index.html

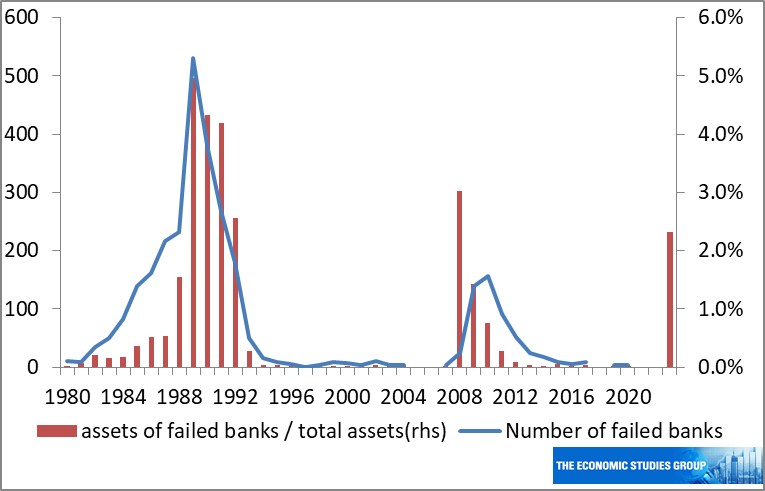

The next major banking crisis took place in the 1980s with the extraordinary upsurge in the number of bank failures. The Q regulation, which capped interest rates for deposits, expired in 1986 and as competition intensified, and significant steps were taken to de-regulate the banking industry, (Garn-St. Germain Act, 1982), a large number of banks failed, primarily in the savings and loan industry. The causes for these failures were a) extremely high interest rates, which forced institutions to pay higher deposit rates, b) regulatory changes that enabled them to diversify their investments into more profitable but riskier areas, and lastly c) a series of severe regional and sectoral recessions and consequently the national economic downturn. From 1984 to 1994, more than 1,600 FDIC-insured banks closed or bailed out, more than in any period since the establishment of federal deposit insurance back in the 1930s. (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of failed banks and their assets as a percentage of the total banking system assets, 1980-2022.

Source: FDIC

As a result, in 1994, Congress passed the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act, allowing banks to operate nationally, but in 1999, the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act essentially repealed Glass–Steagall by allowing commercial bank holding companies to merge with other financial participants like investment banks, or insurance companies.

The severity of the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis impacted the sixth-largest bank, Washington Mutual, making it the largest bankruptcy in history with $ 307 billion in assets, while IndyMac’s failure in June 2008 was the most expensive bankruptcy that cost the FDIC $ 12 billion. Over the following five years, approximately 500 banks failed, leading to a total loss of $73 billion for the FDIC. The deposit insurance fund (DIF) fell to the lowest point in its history, a negative $20.9 billion on an accounting basis, by year-end 2009. It is noteworthy to mention that following the onset of the crisis, Goldman Sachs became one of the largest Bank Holding Companies.

Against this backdrop, Congress decided to tighten regulation with the complex Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act enacted in 2010. The complexity of the Dodd-Frank Act (such as increased reporting requirements for relevant banks) increased compliance costs, probably relatively more for smaller banks than for larger banks. This was a major factor in the US banking system losing one-third of its remaining independent banks between 2008 and 2018.Finally, in 2018, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act relaxed financial regulations imposed by Dodd-Frank and raised the threshold at which a bank would be considered “too big to fail” from $50 billion to $250 billion. The immediate ramifications were apparent with the failures of SVB (the second largest failure in the history) and other banks of noticeable significance.

The rise of the alternative Financial Institutions

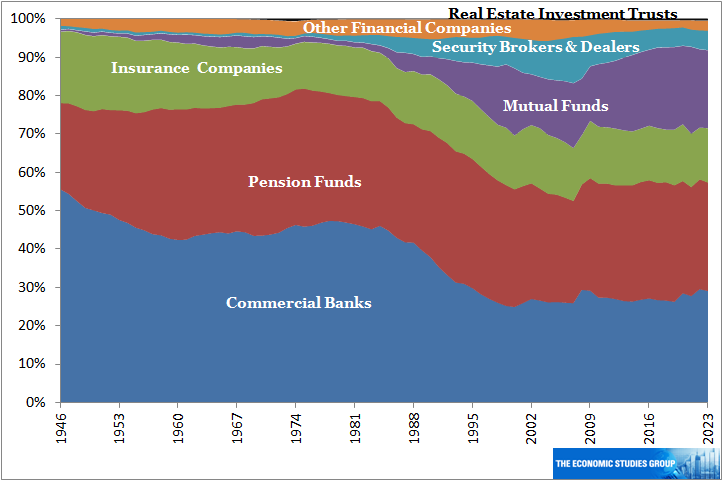

Another significant distinction between the US banking system and the rest of the world is the prominence of the other non-banks financial institution participants in the market. The Glass-Steagall Act not only increased the number of community banks, but it also paved the way for the establishment of other types of financial institutions as alternate sources of capital for businesses. The forms include Insurance Companies, Pension Funds, Mutual Funds, Brokers and Dealers and other financial companies that have come to control large shares of the total assets in the financial markets. The enriched and much more developed financial environment stands in stark contrast to other world systems, like Germany’s where banks take the center stage in terms of financing of private enterprises.

Figure 2. Shares of assets of Financial Institutions, USA.

Source: FRED, Saint Louis, FED.

In terms of assets, the market share of the banking system compared to the other sources of funding is around 30%, with pension funds’ share coming second. (But we should point out that asset trends could not be a good indicator for market share and volume activity because banks are engaging in off-balance -sheet activities like line of credits for enterprises that are not included in total assets). As figure 2 shows, in March 2000, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act had halted the trend of declining banking market share, by allowing the banks to offer securities and insurance services, but only through the creation of financial holding companies. This action brought the U.S. banking institutions on par with other global banking institutions.

The Great Consolidation

As noted above, the number of banks, particularly community banks, which the Federal Reserve defines as banks with less than $10 billion in assets, has declined precipitously. Along with bank insolvencies, and largely due to deregulation, there has been a continuous consolidation through mergers and acquisitions. The largest wave of mergers occurred following the crisis among savings and loan associations (S&Ls), as the elimination of state-to-state banking restrictions encouraged larger banks to operate across wider geographical areas and thus grow in size. Almost two thirds of banking institutions have ceased to exist since early 1980 and with a shift in deposits to larger banks. In the 1990’s the average amount of deposits per bank was around $ 330 million, while now the average is over $ 1.3 billion.

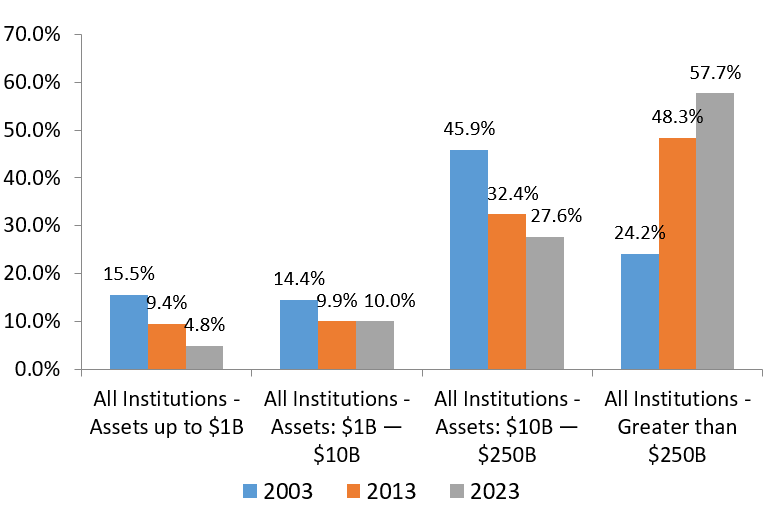

Figure 3. Market shares in the banking system (in terms of assets).

Source: FDIC

Figure 3 depicts the distribution of banks by assets since 2003. The share of community banks, had decreased to less than 15% (assets under $10B), while the number of behemoth institutions with assets over $250 billion has surged from four to fourteen banks, bolstering their market share by threefold, to 57.7% at the end of 2023. Despite a dramatic fall in their numbers, community banks remain critical to small company financing, accounting for more than 30% of commercial real estate loans, 31% of agricultural loans, and 36% of loans to small firms.

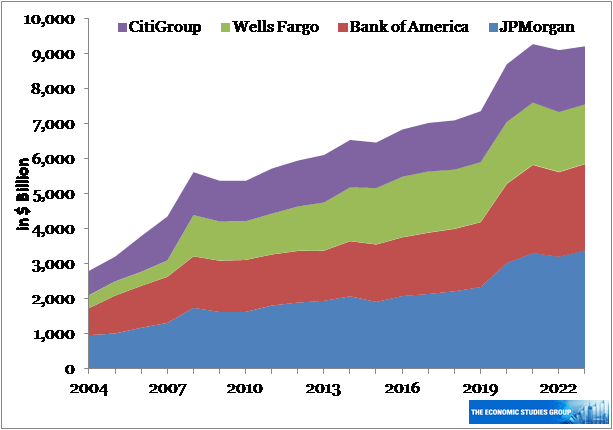

In addition, within the largest banks, the total assets of the top four banking institutions have more than tripled since 2003, totaling over $9 trillion at end 2023 (figure 4).

Figure 4. Total Assets of the top four banks, (in $ billion, current prices).

Source: FDIC

Consolidation appears to be ongoing, particularly in the wake of the recent abrupt demises of banks and the exodus of numerous depositors from small banks, sheltering to “safe heavens” of the larger banks. However, the emergence of new technologies and the rise of fintech companies as key value drivers could drastically disrupt the banking landscape. The new provision called “banking-as-service” which allows a bank, or non-bank financial institution to enter into an agreement with a fintech to provide certain services and products, has the potential to spark further intense competition- not only among banks- and transform the financial service industry.