Fotis Siokis

July 30, 2020

Introduction

Global pandemic events in history, beyond death and destruction, have caused major economic fallout and collapses in international trade. The recent COVID-19 pandemic belongs to this category and is considered the most perilous pandemic in the last 150 years apart from the Spanish influenza. The effects of the pandemic on the global and particularly on the U.S. real economy were immediate and devastating, causing a paralysis in economic activity and a dramatic increase in the unemployment rates, while financial market functioning was severely disrupted. To ensure that the economic damage induced by the pandemic would not be permanent or long lasting in light of these developments, the Federal Reserve (FED) responded rapidly and boldly by expanding the scope of its tools and instituting exceptional and unprecedented measures. In this post we describe the array of both conventional and unconventional monetary tools that were put to work and discuss some of the challenges for monetary policy going forward.

An Outline of Recent Federal Reserve Actions

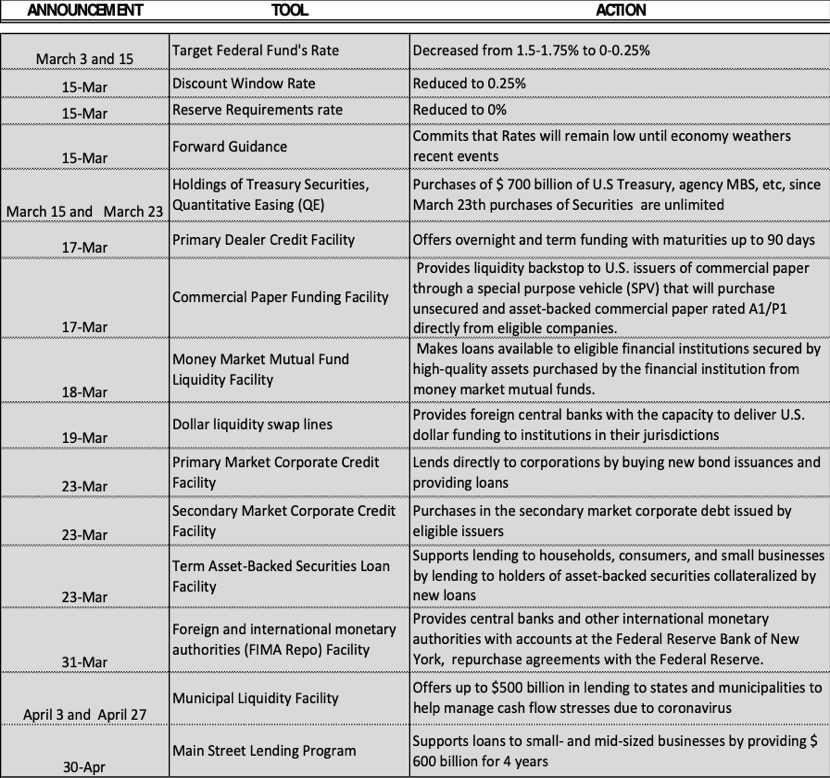

In early March, the Fed went to work beginning with the reduction of the federal funds target rate to near zero in two subsequent not regularly scheduled Fed meetings. Moving beyond the conventional monetary policy tools, in mid-March the Fed proceeded with the use of unconventional tools, many of them employed in the previous financial crisis of 2007-2009. The Fed introduced an aggressive quantitative easing plan with purchases of unlimited amounts of longer-term assets, that is, U.S. Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities (ABS). The stated purpose of the purchases was to improve liquidity in the treasury and ABS markets. Similarly, the Fed utilized a variety of liquidity facilities, ranging from U.S. dollar swap lines to primary- and secondary-market corporate and municipal liquidity facilities, to main street new and expanded loan facilities for small- to medium-size enterprises. Although the analysis of all liquidity facilities initiatives is not within the scope of this article, we present them on Table 1.

Table 1: The FED’s action in response to the coronavirus threat

Source: Federal Reserve Board

We also discuss two main initiatives, namely the Commercial Paper Funding Facility and the introduction of a new-implemented measure, the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility. The reader should consult https://www.brookings.edu/research/fed-response-to-covid19/ for a thorough analysis of all facilities.

Two Liquidity Facilities explained

- Commercial Paper Funding Facility.

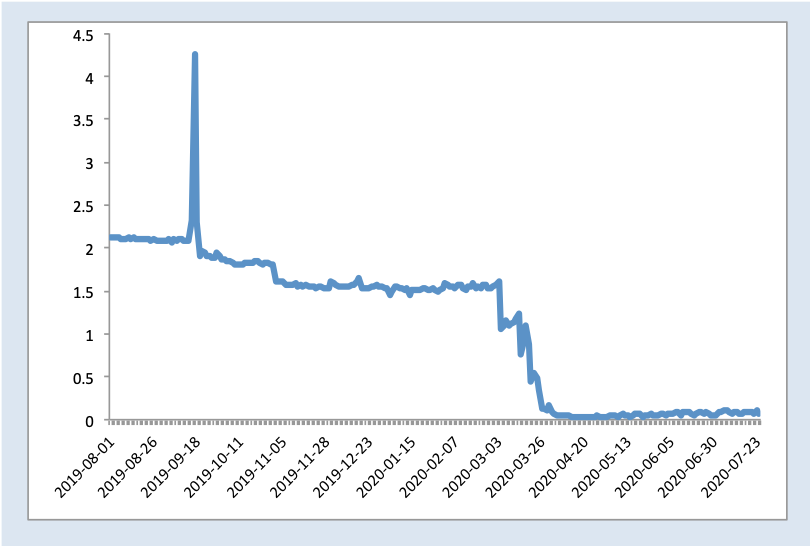

The Fed introduced for the second time the Commercial Paper Funding Facility in an attempt to provide ample liquidity and to encourage investors to reengage in term lending in the market. It was first created on October 27, 2008, as a result of the credit crunch faced by the financial intermediaries. Commercial paper is a short-term mostly unsecured debt instrument, issued with a discount, by corporations. Its purpose is to finance a wide range of economic activity and tends to have very short maturities ranging from a few days to several months. As an instrument, commercial paper is used widely for financing short-term liabilities. But because of the COVID-19, the market was placed under severe pressure. With very limited market demand, and investors reluctant in assuming unsecured debt, corporations were constrained and unable to issue longer-term commercial paper. The Fed, as of April 6th, and acting as a Lender of Last Resort began making purchases, mostly of high-rated eligible 3-month commercial paper (both unsecured and asset backed paper). The purchases are made through the employment of a Special Purpose Vehicle with a private corporation to serve as the investment manager. Since the introduction of this specific facility, the interest rates for all grade paper seem to have fallen (figure 1).

Figure 1. Interest rate on overnight AA Nonfinancial Commercial Paper

Source: Federal Reserve

- Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility.

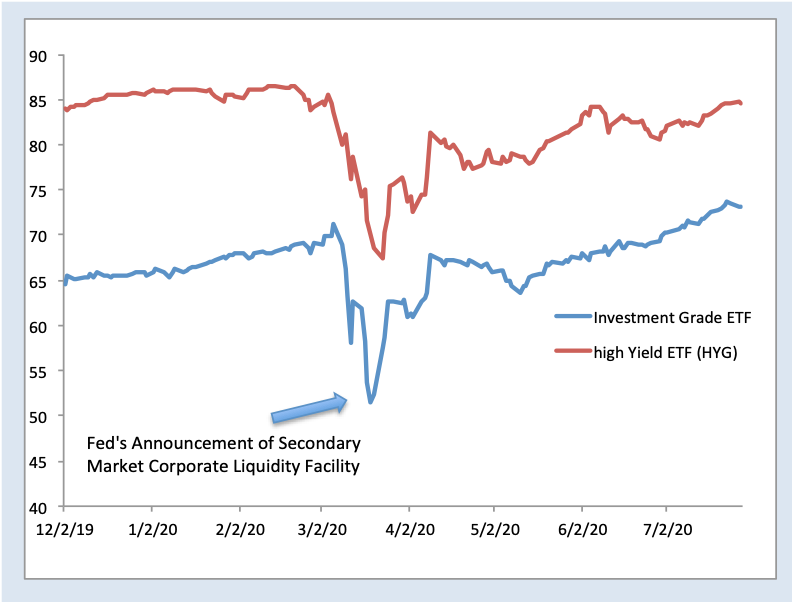

The second facility that distinguished itself from the others is the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility. While other major central banks have regularly used this facility in purchasing investment-grade corporate debt, the Fed engaged in such an action for the first time. Since May 12, it started purchasing exchange-traded funds (ETFs), and bonds mainly with investment grade of BBB and higher, in order to provide ample liquidity to corporates and calm down the volatile bond markets. As of May 20, the Fed holds around $1.8 billion of ETFs. The rational of buying ETF’s lies in the fact that such action could impact the prices of a wider spectrum of bonds. However, in addition to investment grade bonds, the Fed engages in ETFs purchases with high yield bonds including the so-called “fallen angels”, corporates that lost their investment grade due to adverse economic conditions. On some occasions “fallen angels” bonds were downgraded to speculative or junk grade. Purchasing of high-yield bonds, and, also investment grade corporate bonds could open Pandora’s box, since not only does the Fed assume credit risk, which could be quite worrisome and constrain the efficacy of monetary policy but also could threaten, along with other multidimensional activities, the Fed’s policy independence. The recent announcement of Hertz’s bankruptcy could be served as an example. Although, Fed’s exposure is limited or non-existent, the assumption of such credit risk could send mixed and blurred signals to the market. The purchases under the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facilities program are made through the introduction of a special purchase vehicle and managed by a private firm. Since the introduction of the facility, the index of the high-yield ETFs increased considerably (figure 2).

Figure 2. The evolution of Investment Grade and high-yield ETFs Indexes

Source: Bloomberg

An Anatomy of the Fed’s Balance Sheet and the Emerging Challenges

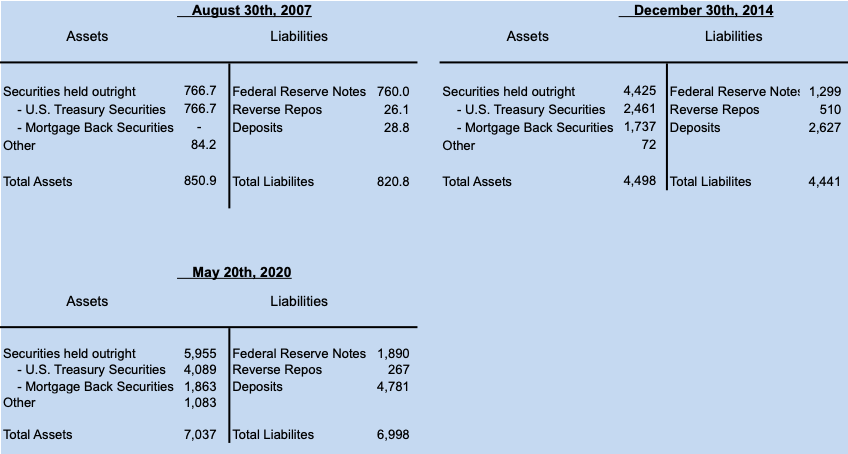

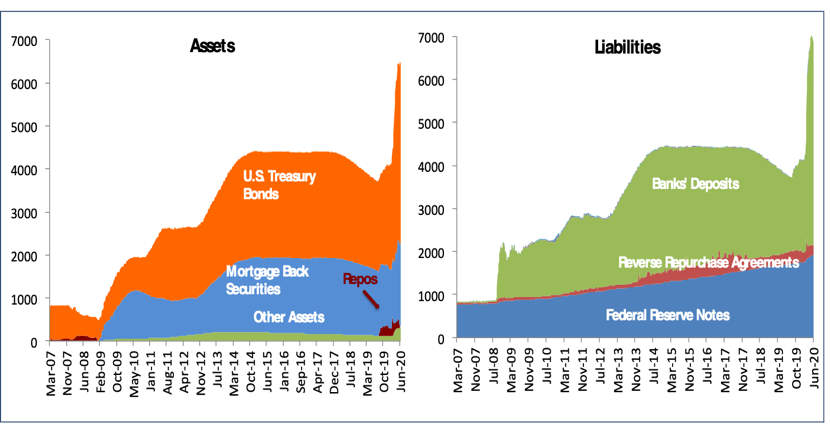

The particularly aggressive response to the coronavirus crisis caused an enormous expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet, much higher than the already-elevated levels generated by the Great Recession crisis. The Fed’s balance sheet consists of assets and liabilities (plus the capital account). The asset side contains mainly the purchases of US treasury debt, Mortgage Back Securities (MBS) and federal agency debt securities, among other items, while the liability side contains Depositary Institutions’ reserves, both required and excess, plus outstanding currency (Federal Reserve Notes). Both of these items, in general, comprise the monetary base. When the Fed conducts expansionary monetary policy, it buys securities from commercial banks (and other dealers) and credits the related fund in depository institutions’ account held at the Fed. Therefore, it should be made clear that an increase in assets causes an increase in liabilities as well. Depository institutions keep required and excess reserves at the Fed for regulation compliance, to take care of transaction obligations, and to build a liquidity buffer in adverse situations. Depository institutions borrow and lend excess reserves at the effective Fed funds rate, which is influenced by the Fed’s policy.

Table 2. The Fed’s balance sheet, selected dates (in $ billions)

Source: Board of Governors, Factors affecting Reserve Balances, Consolidated Statement of Condition of All Federal Reserve Banks

Table 2 depicts the Fed’s balance sheet in three different time periods. Since the onset of the 2007 crisis, the assets as well as the liabilities have grown dramatically as a result of bond buying, commonly known as quantitative easing. The balance sheet expanded from $850 billion at the onset of the Great Recession crisis to almost $ 4.5 trillion by the end of 2014 and to the gargantuan size of $ 7.1 trillion in May 2020. The major component of the assets comprises the holdings of the U.S. Treasury bonds, which grew from $ 768 billion in 2007 to $ 4.4 trillion in 2014 and to approximately $6.0 trillion in May 2020. From the liability side, the reserves have grown from $28 billion prior to the crisis to almost $ 2.6 trillion at end of 2015 and owing to coronavirus monetary policy actions spiked to $ 4.8 trillion on May 20th, 2020, almost 160 times as great as the August 2007 figure. The growth of the balance sheet over time is also depicted in figure 3.

Figure 3. The evolution of the Fed’s balance sheet up to June 2020 (in $ billions)

Source: FRED, Federal Reserve of St. Louis.

The superabundance of reserve balances is attributed predominantly to the vast preponderance of excess reserves. It is argued that this could potentially be inflationary, since banks reserves are a component of the monetary base, which in the last decade grew at an unprecedented pace. However, although the balance sheet expanded to over $ 7 trillion, which ranks the highest among the major central banks, as a ratio to GDP, it is modest. Specifically, the Fed’s holdings are equal to 37% of GDP, compared with112% for Bank of Japan, 50% for European Central Bank and 57% for the Bank of England.

Conclusion

The recent events of increased purchases of longer-term assets illustrate the fact that central banks will rely more and more on balance sheet policy than on the traditional interest rate policy. Based on market estimates, the Fed’s balance sheet will grow further to the level of $9 as we entered into a deep recession placing over 38 million people out of employment. The liquidity facilities introduced by the Fed, with most of them extended through the end of this year, certainly could not cure the economic damage induced by the pandemic. But it is an imperative and a novel effort of mitigating the disastrous effects of it.