James Orr and Zhuo Xi

April 26, 2020

New York, along with the rest of the nation and world, is in the midst of the coronavirus crisis. It is hard to comprehend the tragic loss of more than almost 17,000 lives (as of April 27) statewide including more than 11,000 in New York City. The state’s shelter-in-place order for all residents and the closure of all non-essential businesses was initiated on March 20 and remains in effect.

Recent business surveys and labor market indicators show a significant economic fallout from the virus and containment efforts across the state. While the extent of the economic downturn from the crisis is not known at this time, policy discussions have turned to when, how and how fast to reopen the economy. In this post we look for insights from two earlier crises that New York City has withstood–the 9/11 terror attack and the 2007-09 Great Recession. But the scale of the current downturn will likely be deeper than any of these events, so we also look at the recovery of the New Orleans economy from the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Early Labor Market Indicators of the Depth of the Crisis

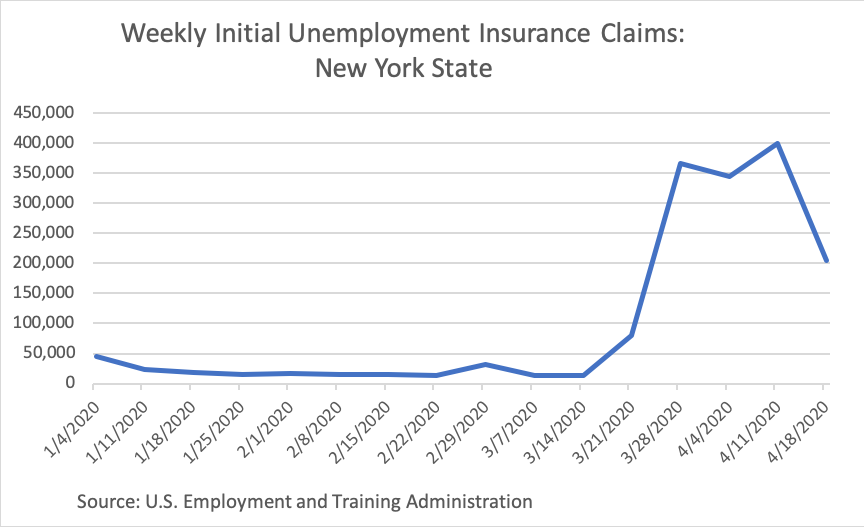

Between the weeks ending March 14 and April 18, the period since the start of the coronavirus crisis, roughly 1.4 million workers, about 15% of the labor force, filed initial claims for Unemployment Insurance in New York State. The largest number filed in the consumer-oriented Accommodation and Food Service, Health Care and Social Assistance, and Retail Trade industries, and also Construction, in all about 60% of the total. Relatively less claims have been filed to date in the more office-intensive Information, Finance and Insurance, and Professional, Scientific and Technical Services industries. Relative to the past two crises, this is an unprecedented increase as statewide weekly claims rarely arose above 50,000.

Downturn and Recovery in New York City from Past Crises

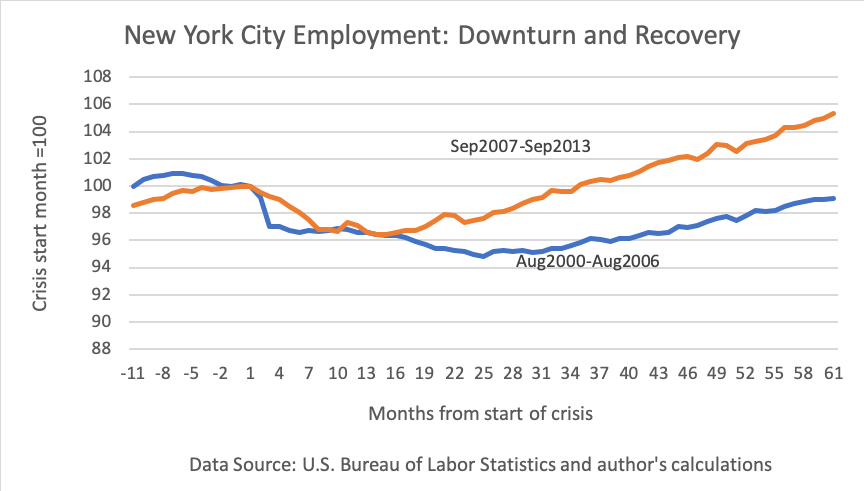

How might a recovery from the crisis play out in New York City? The city’s recovery from two major crises during the past two decades—the 9/11 attack and the Great Recession–offers some insight into the factors supporting a recovery of employment. In the chart below we label employment in the crisis start month as 100 and plot an index of monthly employment 12 months prior to and 60 months after the start.

The 9/11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., was entirely unexpected and led to the loss of about 3,000 lives and, in New York City, heavily damaged the public transportation infrastructure, damaged or destroyed more than 30 million square feet of office space, and disrupted many financial firms located near the site.

In the two months after the attack, employment in the city dropped by roughly 90,000, a decline of 2.7%, and losses reached 5.0% by July 2003. But, the national economy had entered a recession in March of 2001 and it is estimated that the effects on employment specifically due to the attack had worn off by the end of 2002. The weakness of the national economy, and the “jobless recovery” that characterized the period was one factor in the city’s weak recovery.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack, concerns centered on whether Lower Manhattan would be able to repair the damage and avoid any permanent impacts as a location for business and residences. The outcome was not nearly as bad as some of the worst case scenarios. The Federal policy response included assistance with the cleanup of the site, meeting a variety of immediate needs of households, and giving financial incentives to rebuild, work and live in Lower Manhattan. A look at the city’s growth potential at the time pointed to the presence of a number of growing sectors and reasonably sound local finances, among other factors, and when combined with the Federal policy response gave reasons to think the area could recover. A report highlights the resilience of the Lower Manhattan area, which is now a relatively thriving residential and commercial area.

The Great Recession, lasting from late 2007 to mid-2009, was a home-grown nationwide housing crisis that developed into a full-blown financial crisis. Employment growth in the city turned negative in September of 2008 as several major financial institutions failed or underwent significant restructuring. Employment declined along with the nation as the recession worsened and the city lost roughly 160,000 jobs, or about 4.4% of total employment. While the city was spared the extremes of the crisis in housing compared to other parts of the nation, as there was a fear that a severe downturn in financial sector would harm the city’s prospects for recovery.

The policy responses to the recession included a $700 billion fiscal package, the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), about 2.6% of GDP, for expanded unemployment insurance benefits, aid to support state and local government revenues, and funding for infrastructure projects. Monetary policy response was also supporting recovery through lower interest rates, Treasury bond purchases, and a variety of liquidity facilities set up to help stabilize financial markets.

The recovery of employment to its level at the start of the crisis took almost three years, though it occurred quicker and more strongly in New York City than in the nation. The city’s financial sector did suffer, losing almost 20% of employment. But, while Wall Street was still shedding jobs, the city’s gains came from Main Street—a diversified set of local industries not directly linked to financial activities, such as retail trade, leisure and hospitality, professional and business services, and education and health services.

From these experiences, the elements of a recovery include a fundamentally healthy local economy, a growing national economy and effective Federal aid. Unlike the earlier two crises, how the city gets fully back to business will also depend on medical advances in treatment and prevention of the coronavirus. At the time of the crisis the city’s economy was growing though the pace was slowing and the probability of a national recession was relatively low but rising. The Federal response to the crisis includes a spending package, the CARES Act, about 10% of GDP, targeting aid to unemployed workers, state and local governments and small business, among others. Another proposed bill would help hospitals and small businesses. Broad financial assistance is also being provided economywide through the Federal Reserve. It remains to be seen if this fiscal and monetary efforts will be substantial enough in light of the huge and ongoing hit to output, unemployment and state and local budgets. A recent report presents preliminary estimates of a decline of roughly 10 percent of city employment through the first quarter of 2021, larger than in the earlier two crises, followed by a gradual recovery.

The Example of Hurricane Katrina

The scale of the current coronavirus crisis in New York City compels a comparison with the experiences of New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina in August 2005. The extensive damage to that city’s residences and infrastructure and the loss of life, over 1200 people died directly from the storm, made it one of the worst in U.S. history. The city and region turned out to be unprepared for the storm as the levees were unable to prevent the flooding of 80% of the city.

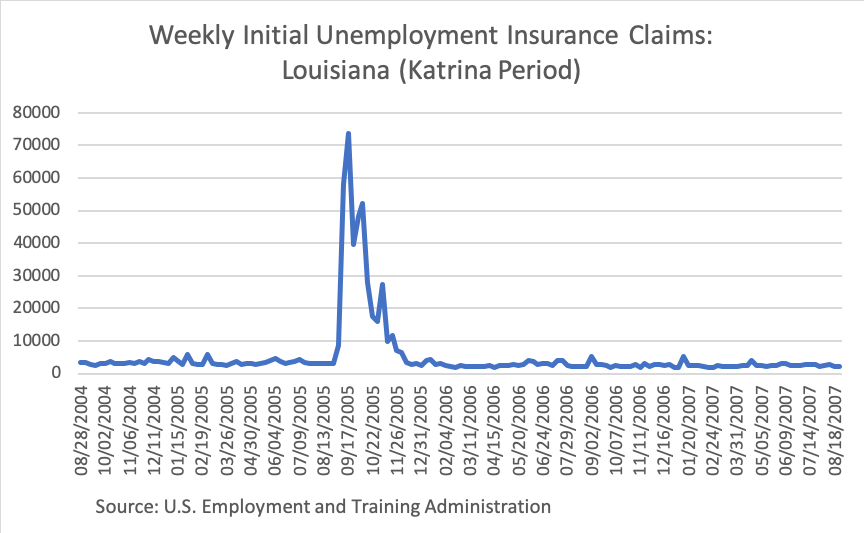

Like New York, filings for initial claims rose sharply across Louisiana in the weeks following the storm to unprecedented levels. One analysis of the early weeks of unemployment claims nationally notes the similarity with those a natural disaster, such as Hurricane Katrina. There, the impact on workers in Louisiana can be seen in the highly concentrated filings in the weeks immediately following the hurricane.

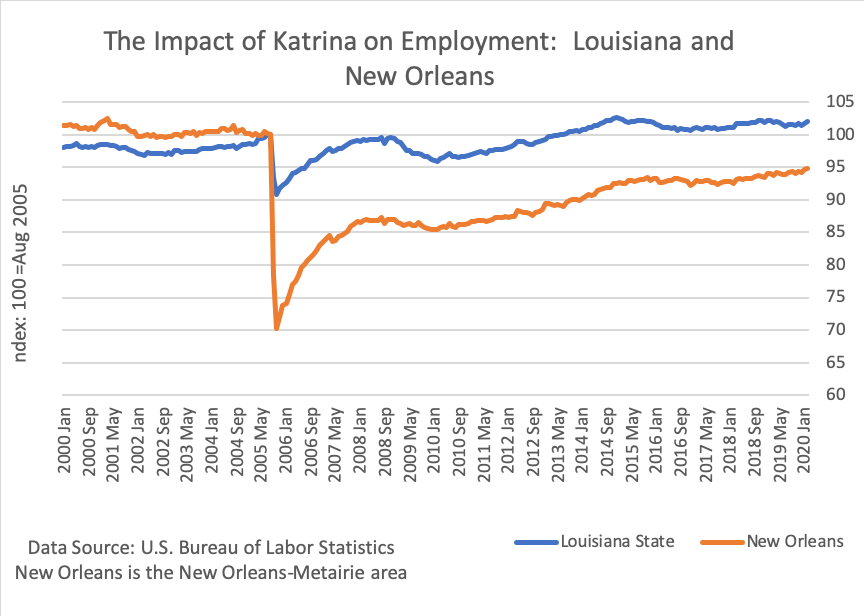

A similarity with the developing data in New York City can also be seen in the rapid loss of employment. The monthly index of employment plotted below shows that in the two months following the storm employment in New Orleans had declined by 25%.

What is unlike New York, and New York City, is that the immediate policy response to the storm included a mandatory evacuation order resulting in 400,000 residents leaving the city and more than one million residents leaving Southeast Louisiana. The population fell by more than one half in the year following the hurricane and still remains 20% lower than its pre-storm level, and the number of businesses in the city is still below its pre-hurricane level. And after a decade the levees had been rebuilt but the city is still considered to be at risk of another major storm.

So while there was initially a v-shaped recovery taking hold, it did not last. Statewide, Louisiana has recovered to its pre-Katrina employment levels in about three years but New Orleans employment has still not fully recovered. The Federal response to the storm was deemed by many to have been slow. A number of residents who left the area permanently relocated to other areas and several low-income neighborhoods were never rebuilt.

Obviously a lot of the dynamics of the recovery of New Orleans are not present in New York City. In particular, business owners and workers have borne the brunt of the impact while infrastructure, stores and other workplaces remain largely intact. The impact on the physical infrastructure in New York would depend on any changes to how business, transportation and other functions requiring close contact are to be conducted going forward. But also obviously this is a scenario we would not like to see develop in the city.