Fotios Siokis

March 04, 2019

Part II

With the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 and the transmission of the crisis to world financial markets, financial liquidity started to drain and investors’ confidence began to deteriorate. Central banks around the globe initiated unprecedented expansions of their liquidity facilities aimed at preventing the collapse of their banking systems and their economies.

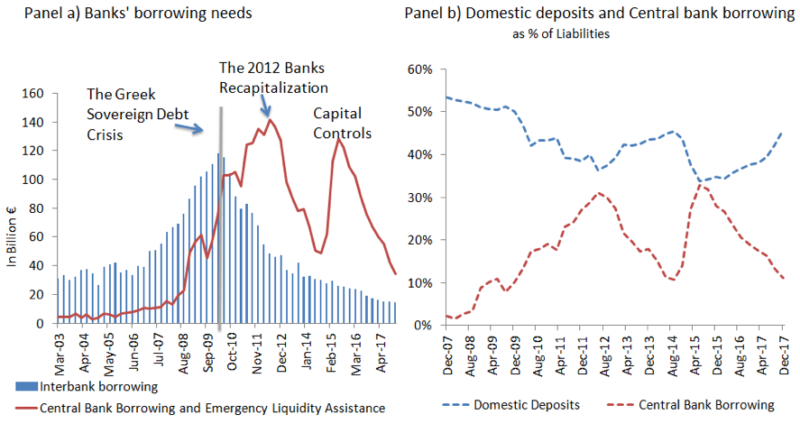

The Greek banking system found itself at the epicenter of a great sovereign debt crisis, trapped in a vicious cycle, exacerbated by a deep and prolonged recession that lasted nearly eight years. The sharp disruption in financial intermediation and the threat to bank solvency forced the authorities to bail out the more important banks. Throughout the crisis, the financial authorities responded numerous times to the liquidity strain by injecting Euro-system funds (figure 1, panel a). From August 2011, the European Central Bank authorized a special credit line to the Greek banking system, called the Emergency Liquidity Assistance, upon which the banks depended heavily, especially during periods of deposit withdrawals. In June 2012, after the restructuring of sovereign debt, European Central Bank funding amounted to around 136 billion euro and came almost exclusively in the form of Emergency Liquidity Assistance. The final resort to this expensive source of funds took place in May 2015, as deposits again dropped substantially when negotiations between the newly elected government and its creditors had stalled (figure 1, panel b). Alongside the provision of liquidity, the authorities initiated three rounds of successive capitalizations for the banking system, with large capital injections equal to about 43 billion euros.

Figure 1. Banks’ borrowing needs and Domestic deposits

Source: Bank of Greece

Attempts at reviving credit growth in the Greek Economy

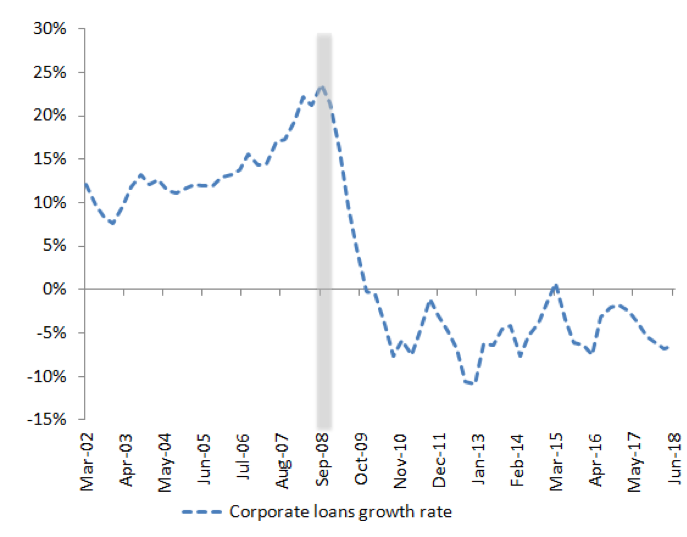

The tightened lending conditions had severe consequences for the majority of credit-dependent, small-to-medium enterprises, and thus for the Greek economy as a whole. The critical significance of small-to-medium enterprises is documented in the survey regularly conducted by the ECB, which reveals that they contribute roughly 70.2% of the total value-added while accounting for 70.6% of banks’ lending. By contrast, the percentages for the small-to-medium enterprises in the euro-area are 49.9% and 58.1%, respectively. The credit asphyxia became apparent in late 2010 when banks stopped providing loans to corporations and households. According to the following graph, the credit contraction began in November 2008, as the global financial crisis spread to the European Union. Prior to 2008, and with Greece’s entry to euro-area, banks were provided with access to low-cost credit and to ample liquidity. The banks embraced retail and corporate lending, which entailed excessive leverage. Mortgage loans rose by an average of 30% year-on-year, topping all other euro-area countries, while consumer loans increased by 28% over the same time period.

Figure 2. Corporate lending activity ( year over year %)

Source: Bank of Greece

Despite all above efforts and with an improved Banks Capital Adequacy Ratio to 18%, compared to an average of 16.7% for the main banks in the euro-area, Greek banks remained still unable to finance the economy. Loans to households are receding while credit to corporations is stagnating (figure 2). The failing attempts of reviving credit growth is attributed to the large stock of non-performing loans (NPLs) held by banks on their balance sheet. A high NPL ratio, or the percentage of the value of total loans that are non-performing as a share of total loans, requires banks to put more capital aside thus reducing credit availability. In addition, banks with a high NPL stock become more risk-averse and cautious in their lending and tend to focus mainly on improving asset quality.

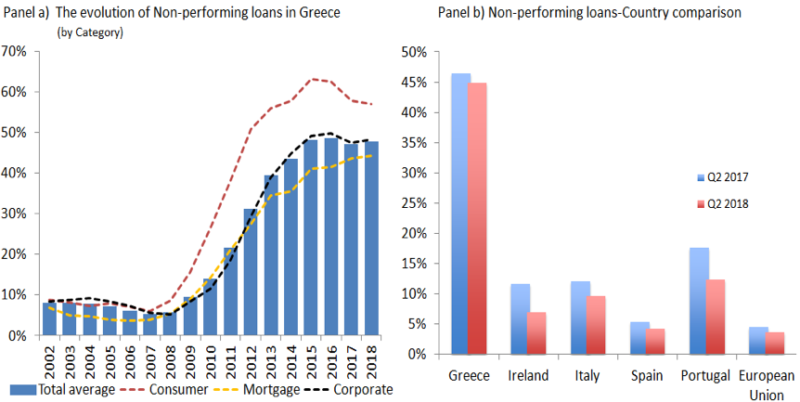

The Non-Performing Loans Issue

The NPLs ratio rose from 4.6% in 2007 to 9.1% in 2010 and to 31.9% in 2013 before surging to 47.5% in 2016 (figure 3, panel a). As of the second quarter of 2018, NPLs NPL stood at 45.5% of total loans, the largest percentage by far within the Euro-area (figure 3, panel b). It is now common knowledge that the accumulation of NPLs on their balance sheets explains why the banks have been unable to support any resumption of credit expansion and thus economic growth.

Figure 3. Non-performing loans as % of total gross loans

Source: Bank of Greece and European Central Bank

The severity of the depression had led to the NPLs rise to this extraordinary level. Contributing to this increase were problematic corporate governance practices with poor management and inadequate assessment of credit risks. Loans granted in the pre-crisis period to political parties and to corporations with low creditworthiness but privileged relationships with banks are a notable example. Reform of corporate governance practice was, in fact, raised as a precondition for the 2015 capitalization. Based on the “fit and proper” criterion, most board members of the banks were evaluated and some replaced to ensure the safety and soundness of the banks on boards they served.

Also, an important dimension of the NPLs problem lies in the existence of a significant percentage of borrowers who have the capacity of servicing their loans but have decided not to do so, hoping for a future major hair-cut of their loans. The so-called strategic or willful defaulters, differed from the distressed defaulters are taking advantage of debtor protection program and of the absence of any consequences. They comprise around one-fourth of the total NPLs.

Conclusion and Lessons Learned from the Sovereign Crisis

The sovereign debt crisis revealed a strong negative feedback loop between the government and the domestic banking system. Banks supported Greek sovereign bond prices by accumulating Greek government bonds during the crisis, while the government provided guarantees and bailout funds. The resultant fiscal costs and lack of lending opportunities to corporations, which increased sovereign distress even further, should raise serious concerns regarding this relationship.

The sovereign debt crisis placed the banking sector in a very vulnerable position, threatened by insolvency and poor loan performance. High credit growth along with the excessive risk-taking for loans granted to entities with minimal creditworthiness and the great reliance on accumulated domestic sovereign bonds remain key issues. After the recent experience, the European Central Bank has put a ceiling in domestic government bonds accumulation.

In conclusion, the Greek economy needs higher and sustained growth. Restoring full confidence in the financial system and reviving bank lending, especially to corporations, is paramount. But the large percentage of NPLs stands in the way, limiting the ability of the banks to support economic growth. They need to clear the bad loans off their balance sheets. Otherwise, as the International Monetary Fund has recently announced, banks will continue to need fresh capital injections in a vicious cycle seemingly without end.