Fotios Siokis

February 19, 2019

Part I

The Greek economy appears finally to have turned the corner with the Government’s announcement, in August 2018, that the country has exited its third bailout package. This article examines the role of banks in the recovery and the debt crisis.

Economic activity has registered positive growth for two consecutive years and seems to be on track to maintain that growth, albeit at just under 2%, for the next two years. As the government proceeds without a new line of credit from its creditors, Greek banks seem incapable of contributing to any further economic expansion. They remain vulnerable, still burdened by the gigantic number of the non-performing loans (NPLs) and therefore poorly positioned to finance new investment. The NPL ratio, now close to 45% of total loans, greatly undermines the banks’ ability to lend to the private sector.

In this context, we attempt to answer the question: why did the Greek banks get into such trouble? A series of two parts, which are closely related helps to explain how, the banking system evolved during the sovereign crisis. The first part deals with the impact of the crisis to the banking system, and the efforts made by the authorities to keep the banking system solvent. The second part deals with banks’ lending activities and the rise of the non-performing loans. We conclude with some lessons learned from the crisis.

The Acute Face of the Sovereign Crisis

The Greek banking system found itself at the epicenter of a great sovereign debt crisis and the attendant austerity program. It became trapped in a vicious cycle, which was exacerbated by a deep and prolonged recession that lasted nearly eight years. Unlike recent experiences in Ireland, and to a lesser extent Spain and Italy, the undercapitalization of the Greek banking system in 2012 was the result of the Greek sovereign debt crisis and, to a lesser extent, the unrestrained growth of lending following Greece’s entry into the euro-area.

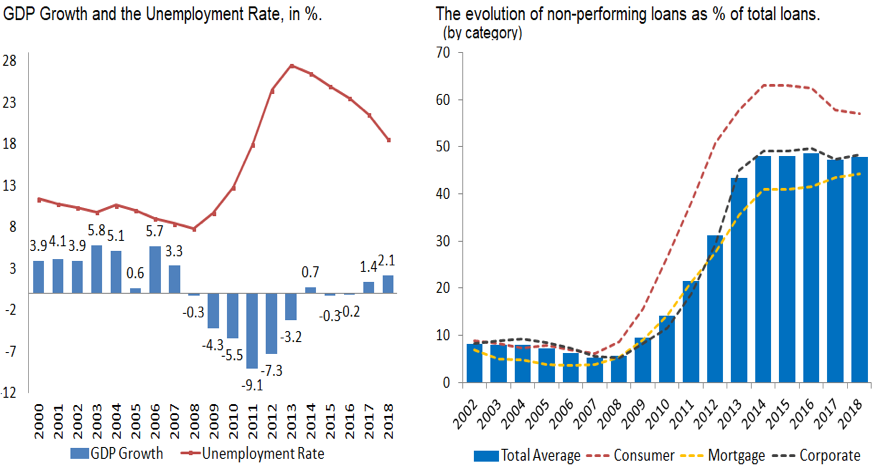

The sovereign debt crisis emerged after the announcement by EU (European Union) authorities in 2010 that the Greek budget deficit for 2009 was 15.6% of GDP, four times higher than reported by the previous government, while measures of the public debt were revised sharply upwards to 126.7% of GDP. Once fiscal consolidation efforts took center stage, unprecedented public spending cuts and sizeable tax increases, along with the weakness of the euro-area economy, led to a reduction in output by about 28% through 2013 and a rise in the unemployment rate to a staggering 27.8%. As the country moved into the heart of the crisis, the deep recession and the austerity measures implemented by successive governments caused a number of corporations and households to default on their loans. As we discuss in part II of this series, the NPL ratio rose sharply and remains elevated.

Source: Eurostat and Bank of Greece

Source: Eurostat and Bank of Greece

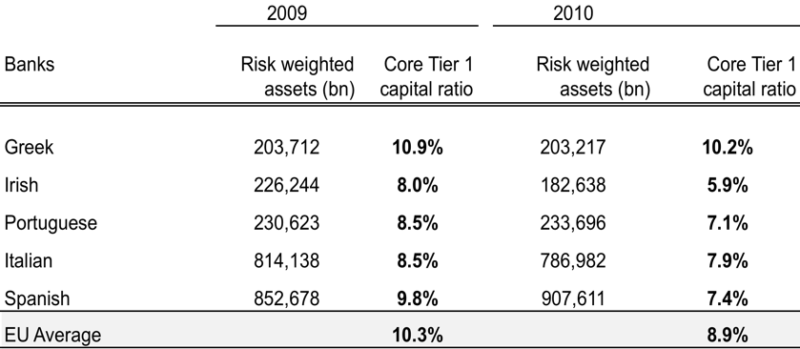

Up until 2010, the Greek banking system was regarded as sound thanks to its limited exposure to “toxic financial instruments” and its strong capital base which, coupled with steady support from the Bank of Greece (BoG) and the ECB, ensured stability of the Greek banking system during the first two years of the world financial crisis.

Table 1. Risk-weighted Assets and Core Capital for Selected Banking Systems

Source: European Banking Authority, stress tests as of 2010, participating banks

Source: European Banking Authority, stress tests as of 2010, participating banks

However, Greek banks were hit hard, as the uncertain value of sovereign debt and defaults spawned a series of downgrades of Greek debt and led to the first run on the banks. From December 2009 to end of 2011, households and corporations withdrew vast sums from the banks and deposits fell by more than 25%. The pressure on liquidity escalated further as successive downgrades of Greek bond ratings resulted in a higher cost of banks’ borrowing in wholesale and interbank markets.

The sovereign-bank nexus and the domestic bias

In early 2012, the banks brought to their knees, when the biggest sovereign-debt restructuring process in modern history took place. The orderly debt exchange of old bonds for new ones with longer maturities, known as Private Sector Involvement (PSI), entailed a 53.3% haircut on the nominal value of old bonds. In light of their large exposure to Greek government bonds , the banks took a huge loss of about 38 billion euros. They suffered bankruptcy with the depletion of their equity capital.

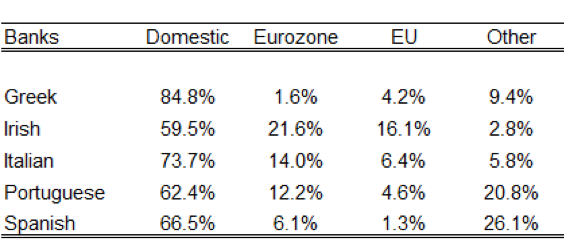

The PSI was especially costly to Greek banks as it followed on the heavy exposure to sovereign risk that developed as banks had added considerably to their holdings of government bonds, particularly between 2009-2011. Despite the evidence that substantial cross-border sovereign bond investment among member states of the Euro-zone facilitated financial integration, a “domestic bias” persisted strongly in some countries, especially in Greece. At the end of 2010, banks held in their investment portfolio a much greater portion of domestic sovereign debt compared to other countries facing similar circumstances. (Table 2).

Table 2. Sovereign Debt held by Banks Source: European Banking Authority, stress tests as of 2010, participating banks

Source: European Banking Authority, stress tests as of 2010, participating banks

Large holding of domestic sovereign bonds, which are regarded as risk-free within the regulatory framework, provide the collateral needed to access liquidity from interbank markets and the Central Bank. At the same time, excessive holdings of domestic sovereign debt imply that, in times of crisis when sovereign risk increases – as in the case of Greece – access to wholesale funds and deposits (liquidity) can suddenly disappear. The composition of banks’ funding must then shift to an increasing reliance on Central Bank liquidity. Negative effects on the real economy follow from the transmission of credit-risk associated with sovereign debt to lending and investment activities in the private sector. An interesting question is why Greek banks at that time relied so heavily on domestic government bonds, knowing that every deterioration in sovereign creditworthiness reduces the market value of their domestic sovereign debt portfolio.

Bank Capitalizations and the Restructuring Phase

The sharp disruption in financial intermediation and the threat to bank solvency forced the authorities to bail out the more important banks. Stress tests concluded that necessary re-capitalization amounted to 28.6 billion euros. A newly created Hellenic Financial Stability Fund financed 25 billion euros, about 90% of the total, while the rest came from the private sector. The share capital increase was completed in June 2013. A puzzling aspect of this episode concerns the fact that the authorities knew the banks had to be recapitalized because of the forced reduction in the nominal price of government bonds. Why, then, didn’t they leave the banks out of the PSI? Probably, the answer lies in the fact that the banks held a huge amount of the sovereign debt, and by excluding them, it would have compromised the outcomes of the debt-restructuring attempt.

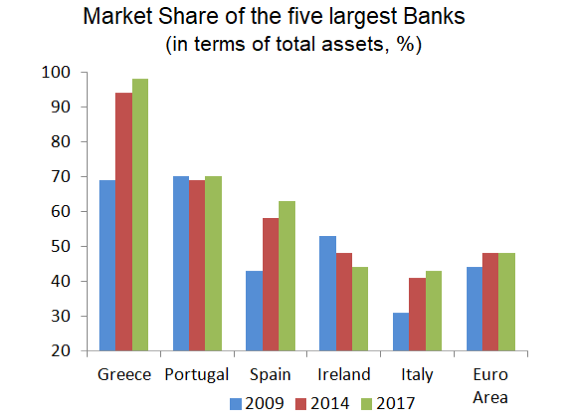

In an effort to strengthen the financial system and restore public confidence, the financial authorities proceeded with an extensive restructuring and consolidation program for the Greek banking system, reducing capacity in the industry through mergers and takeovers and the liquidation of a number of commercial and cooperative banks. By 2014 the banking system recorded the largest decrease in the number of banks among the euro-area systems, and the new roadmap comprised only four major-systemic banks, commanding more than 94% of the total market share in terms of assets.

Another important recapitalization of domestic banks took place at the end of 2015. Following early elections in January 2015, the breakdown of the prolonged negotiations with creditors (from late 2014-June 2015) triggered a major bank-run, amounting to almost 42 billion euros. The Bank of Greece imposed a bank holiday in late June 2015, followed by capital controls. These dire events induced European authorities to orchestrate another recapitalization, equal to 14.4 billion euros. Roughly 10 billion euros was covered by the private sector and the remainder by the financial stability fund. This created a new shareholder landscape as the participation of the fund in previous recapitalizations was heavily diluted. Most of the shares were sold to private investors for a fraction of their nominal prices.

The recapitalization was finalized at the end of 2015, before the introduction of the EU Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive which called for a bail-in solution with a haircut on all unsecured deposits in excess of 100,000 euros. Since most of the large depositors had already withdrawn their funds from the banking system, the remaining deposits were mainly the working capital of small-to-medium enterprises. A haircut on their working capital would have further hurt the economy and put their existence at risk. But although the recapitalization improved the Banks Capital Adequacy Ratio to 18%, compared to an average of 16.7% for the main banks in the euro- area, Greek banks still remained unable to finance the economy. We explore the reasons for this in Part II of this series.