Harvey Gram

June 06, 2018

1. Be Wary of the Words—and the Rhetoric

“Debts” and “deficits” seem to have negative connotations. Still, every debt/liability for one party is a credit/asset for some counter-party who willingly holds the corresponding security; and every deficit has its matching surplus somewhere in a complete and consistent set of accounts. The argument is nevertheless heard that government debt, in particular, is always a burden—a burden on “our grandchildren”, innocent victims of the government’s current profligacy and corresponding deficits that can only be financed by selling more debt. A perfectly sensible question often gets lost in the rhetoric. Is the future cost of servicing government debt larger or smaller than the future benefit associated with debt-financed expenditures? Is it always better to raise taxes to cover the expenditure in question, thereby avoiding the deficits that fuel the rise in debt? Whether or not a particular expenditure is justified should be argued separately from the way in which it is to be financed.

Individuals face such questions all the time. How does the (flow) cost of servicing a mortgage stand up against the expected (flow) benefit of living in a house (a stock) and thereby saving on rent (a flow)? How does the (flow) cost of servicing a student loan stand up against the expected higher (flow) of earnings from having a college degree (a stock)? Would anyone seriously argue that households would be better off without the choice of entering into such debt contracts? That would require saving up enough to buy a house outright before living in it, or paying for an education before benefiting financially from a better paying job? Of course, renting can make more sense than owning for some households (though tax breaks often tell in favor in owning); and success in life comes to some who have only a high school education. Still, these are not arguments for making debt contracts illegal. If borrowers do not understand the terms of debt contracts, greater transparency on the part of the lenders is called for—and may have to be enforced by government regulations.

Certain types of government spending on, say, infrastructure projects benefit the same people who will be taxed to pay interest on the debt issued to pay for the project, just as the owner of a house who makes monthly mortgage payments benefits from the shelter it provides. Such linking of costs and benefits actually occurs when a government dedicates user fees (e.g. tolls) to service the debt issued to pay for new infrastructure (e.g. a bridge or highway) and to maintain it. This is not always easy to do, but any informed discussion of the burden of the debt ought to be concerned with such matters. In any case, there is no more sense to a blanket condemnation of government debt, especially when the government can borrow long-term at relatively low interest rates, than there is to a blanket condemnation of corporate and personal debt.

Deficit “hawks” respond to such arguments with a seemingly straightforward question: “But, what about the day when the debt comes due?” The answer is that it comes due every day. New bonds routinely replace maturing debt. The “hawks” retort: “And, what if the interest rate on replacement debt is higher? Sounds like a Ponzi scheme to me!” Well, sometimes interest rates on new debt are lower, causing total debt service actually to fall, but that is not an answer. There is a germ of truth in the “hawks” fear-mongering, but it has nothing to do with some final day of reckoning. After all, the holders of government debt are quite happy with their assets, and, if the bonds in their portfolios mature, new ones can be purchased to maintain the desired flow of interest income. So, what is that germ of truth in the argument of the deficit “hawks” who see in every increase of outstanding government debt a harbinger of immanent economic collapse?

The ratio of government debt to gross domestic product is a legitimate concern. Its numerical value can be confusing, however, because GDP is an annual flow. Measure GDP on a six-month basis and the debt to GDP ratio immediately doubles; measure it on a decennial basis and the same ratio suddenly falls to one-tenth its “annual” value. A ratio that does not suffer from this defect is debt-service (interest) divided by GDP. Both are flows over the same period whatever that may be.

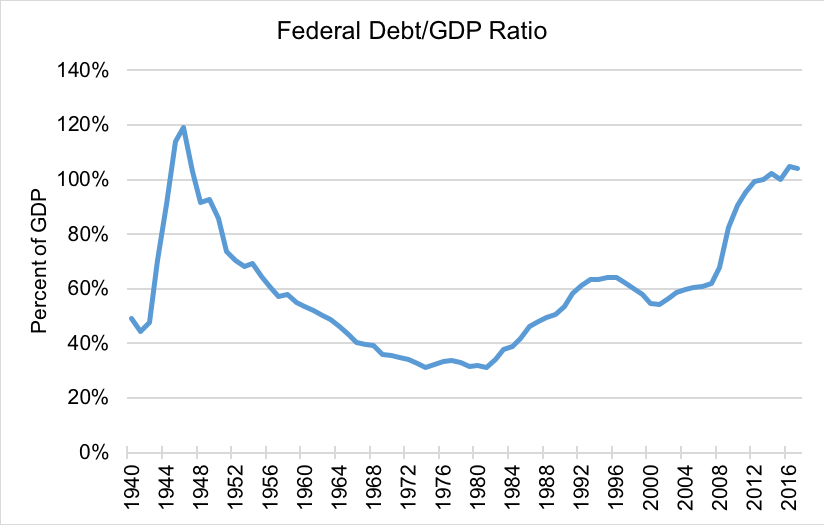

The Federal Debt/GDP ratio peaked at 119% in 1946 following World War II during which purchases of debt by the public was advertised as a patriotic duty. The campaign was hugely successful, thereby funding the war effort without a huge tax increase while endowing the public with an income earning asset. The Federal Debt/GDP ratio then fell steadily to about 31% in 1981, primarily because of rising GDP (although there were six surplus years). More recently, the debt/GDP ratio rose sharply in the years following the recent financial crisis and is now about 104% of GDP. Canada’s ratio is somewhat lower; Japan’s is well over twice the US ratio.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Series GFDGDPA188S

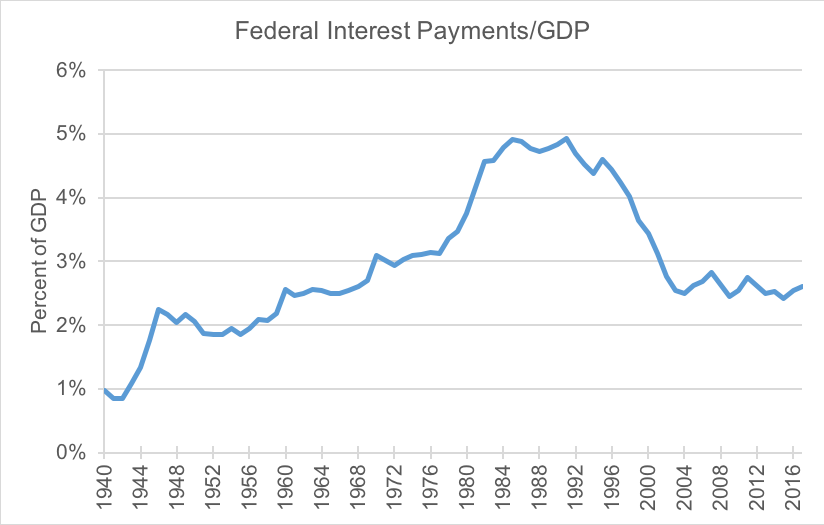

Even a sharp rise in the Federal debt/GDP ratio need not be accompanied by a similar trend in the ratio of Federal interest payments to GDP. At 2.6% of GDP, the present ratio is about three times its minimum 1944 value, but well under its 1991 value of almost 5%. A rising debt/GDP ratio and a simultaneously falling debt-service/GDP ratio simply reflects historically low interest rates on recently issued government debt.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, NIPA Table 3.2, Line 32

A final caution is in order concerning the word “deficit”. Whenever the U.S. Current Account is in deficit, it is necessarily the case that the U.S. Financial Account Balance is in surplus. Our trade surplus in services and our surplus on income account are more than offset by our trade deficit in goods and our excess of taxes and transfers paid over what we receive. There is only one way to finance the resulting Current Account, and that is to sell more claims on future US income than we buy on future foreign income. These are capital account transactions and selling more than we buy is the definition of a surplus. Anyone who prefers the word “surplus” can simply talk about the Financial Account rather than the Current Account, “celebrating” the fact that the U.S. is a “great place” to invest. Don’t be fooled. The Current Account deficit is the same thing (with sign reversed) as the Financial Account surplus! Any policy that changes one will automatically change the other.

2. Conceptual Issues

Because stocks and flows involve time, the question arises: What happens to the distinction when the length of time over which the flows are measured is shortened or lengthened? If we imagine stopping time so that the rivers stop flowing and wind stops blowing, everything becomes a stock because we are stuck in an instant of time. If we lengthen the period of time sufficiently to allow a stock of, say, automobiles, to completely wear out and be replaced with different ones, then the stock has “turned over” and become a flow. The less durable a good, the shorter the time over which a stock becomes a flow. Hence, in the market for fresh milk or fish, it makes analytical sense to treat supply and demand as flows, even though at a moment in time the amounts of fresh milk and fish are stocks. In the market for residential housing, on the other hand, the main influence on price will be the existing stock of previously built houses—the dog that wags the tail in the market for the flow of newly constructed houses.

It always makes sense to ask if a variable is a stock or a flow because it forces one to think about units of measurement. Is labor a stock or a flow? When we see a symbol for labor as an argument in a firm’s production function, it is surely a flow, “work per unit of time” for that is what matters to a process of production yielding a flow of output. At the same time, a worker with particular skills and experience is just as surely an asset, and therefore a stock. Employers, who cannot legally buy and sell their stock of workers—something they can do with their stocks of plant and equipment—often go to considerable trouble to control the workers they do not own. Non-disclosure clauses in employment contracts and non-portable pensions are examples. When economists conceptualize laborers as a stock, they are not pretending that workers are slaves, but simply trying to model the fact that investments by firms in worker training are sometimes curtailed because the “improved” labor-assets can just walk out the door at any time. As for maximizing the flow of work that the stock of labor provides, this involves complex questions of organization and corporate structure, the province of management science.

Knowledge, in general, like the skills and accumulated experience of workers, is a stock. The flows that create knowledge are the activities of teaching and learning, which take time. Knowledge, however, has a vital and distinguishing property. Unlike a stock of machines, which, when used, generally depreciates as a result of wear and tear, knowledge can increase simply by being used and will surely disappear from not being used. Computer-aided storage of knowledge and its retrieval for use brings up the whole question of the relationship between the existing stock of knowledge and the creative process, which is an intrinsic aspect of the ongoing flow activity of production.

Using the conceptual distinction between stocks and flows when considering economic problems, from healthcare to environmental conservation to the development of new technologies, and much else, will always bring clarity to your thinking.