Miguel Acosta-Henao

August 31, 2017

The Fed has started increasing the federal funds rate, reversing its decade long accommodative monetary policy. The last time such a reversal in the Fed policy occurred, the impact on emerging markets in Latin America was deleterious. This article examines if history will repeat itself.

By the end of the 1970s the most important Latin American economies had opened their capital accounts to the rest of the world and received a considerable amount of capital inflows that were financing sovereign debt. However, this ended when the Federal Reserve (FED), led by Paul Volcker, pursued a sharp disinflation, increasing the federal funds rate, and resulting in high capital outflows from emerging markets to the U.S. These flows caused long currency depreciations and increased the risk premium of sovereign bonds in those countries. As a result, as documented by Krugman (2009), Mexico, Argentina and Brazil went into technical default, capital inflows ceased, inflation sky rocketed (especially in Argentina) and these economies, as well as the rest of the region, entered into deep recessions that took a severe toll on Latin America’s potential growth through the 1980s.

Currently, ten years after the start of the great recession, inflation is converging to the FED’s 2% target and the labor market in the U.S. continues giving signals of strength–an unemployment rate of 4.3% and a payroll job growth matching the growth before the start of the crisis in 2007. These facts have led the FED to increase the federal fund’s rate and to announce more hikes during this year.

Latin American countries are not as indebted as they were at the beginning of the 1980s (except for Venezuela) nor do they have the same weak macroeconomic institutions they had in the past. Economic fragilities, however, exist. Between 2003 and 2013 Latin America received a considerable amount of foreign investment. Unlike the 1970s, however, it was in the form of gross capital formation directed to the commodities sector (mainly oil). This meant that governmental borrowing was not as significant as it was thirty years ago. Nevertheless, a reversal of capital flows would still affect the whole external debt of the region, whether is public or private, due to currency depreciation and a negative effect on each economy’s sovereign risk, which could lead these countries to the brink of a recession. One part of this process has already started following the commodity price shocks, with average currency depreciations of 30% between 2014 and 2017 for Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, and Peru.

Sovereign Risk in Latin America

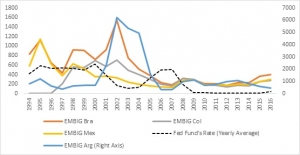

The benchmark estimate of country interest rate spreads for emerging markets is J.P Morgan’s Emerging Market Bond Index Global, EMBIG. The Index, which compares a composite of bonds with different maturities and liquidities in each country with a similar composite for the U.S, reflects sovereign risk in those countries, is available starting in 1994 for selected Latin American countries. Figure 1 shows both the evolution of the EMBIG from 1994 for the most representative emerging countries in Latin America (excluding Venezuela), and of the federal funds rate during the same period.

Figure 1: EMBIG Selected Latin American economies (basis points).

Between 1998 and 2001, most Latin American economies suffered deep recessions that started with the increase in their sovereign risks, as it can be seen in the graph. But, in line with the massive capital inflows that the region received between 2003 and 2013, the EMBIG of each country substantially decreased during those years. It has risen modestly recently, although not at all close to the levels seen before the year 2002.

Impact of the FED Funds Rate on Sovereign Risk in Latin America

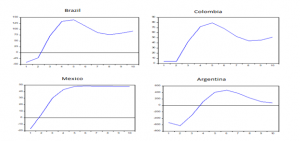

For each country, we estimate an econometric model that allows us to see the response of each country’s sovereign risk to the FED’s rate hike. For each country in the sample, Figure 2 shows the response of sovereign risk to a 100 basis point increase in the federal funds rate.

Figure 2: EMBIG response to a to 100 points increase in the federal funds rate (basis points).

Figure 2 presents the results of our estimation, which show a large and sustained response of interest rates in each of the countries to a rise in the U.S. federal funds rate. These results are in line with those of Uribe and Yue (2006), who show that for a group of emerging markets, an increase in federal funds rate leads country spreads to fall and then display a large, delayed overshooting. Clearly, the results are alarming: an interest rate hike in the U.S. has a permanent negative effect over the country risk for Latin America, let alone a continuous path of interest rate hikes like the one the FED plans to do.

Will history repeat itself?

Contrary to the episode in the 1980s, most Latin American countries have central banks with full independence and explicit inflation targets. External debt as a share of GDP is, on average, less than 70% compared to the 3-digit numbers in the 1980s. Some countries like Colombia have explicit fiscal rules that contribute to smooth the cycle through fiscal policy while committing to keep the public deficit within a defined range. However, it doesn’t mean that the region is completely shielded against the FED’s hike. The increase in country risk compromises investment in countries that still lack physical infrastructure to compete with other emerging countries such as China or a number in South East Asia; the volatility that this brings to the business cycle contributes an increase in uncertainty about the future and may generate misallocation of capital among investors, and pressures over governments to raise taxes and reduce government spending (in order to avoid a down grade in their risk rating) may imply fiscal reforms that seriously slows down (or even contract) the growth rate of the GDP in those countries.

It is then important that not only governments but also central banks among those countries prepare themselves correctly for what may come. Recent literature has pointed out the importance of capital controls in booms and busts as a potential tool to help reduce the volatility of the business cycle. Also, imminent tax reforms like the one Colombia had during 2016 (which aimed to increased tax revenue) could be complemented with institutional reforms that contribute to improving productivity, which has been Latin America’s longer-term problem as shown by Restuccia (2013). All in all, the main point is that, even though the region seems more prepared than before to a FED’s hike, it is still vulnerable according to our empirical analysis; therefore, the region should consider new policy tools as well as important structural reforms to reduce the exposure that it has to foreign interest rate shocks.