Yoshiko Oka

January 10, 2019

On May 25, 2018, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced a proposal to end the International Entrepreneur Rule, which was published at the end of the Obama Administration. Unlike many other countries, the United States has no visa for immigrant entrepreneurs, and many had thought the rule would encourage promising business owners, thereby promoting job growth and innovation. This article explores current entrepreneurship trends in the United States and analyzes how the elimination of the International Entrepreneur Rule would affect the labor market. Current trends suggest a decrease in native-born entrepreneurs, and an analysis of the labor market indicates that elimination of the Rule will exacerbate the declining startup rate.

What is the International Entrepreneur Rule?

The International Entrepreneur Rule is a regulation by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) that encourages promising foreign entrepreneurs to start businesses in the United States. Under the rule, these entrepreneurs are granted a stay of 2.5 years to run their business in the U.S., which can be extended another 2.5 years if the company’s performance meets certain requirements.

Immigrants play a pivotal role in entrepreneurship in the U.S. The proportion of immigrant entrepreneurs has been growing, and the National Foundation of American Policy reports that more than 50% of America’s unicorn companies (startups valued with one billion dollars or more) were founded by immigrants. Currently, the United States does not have a particular visa category targeting foreign entrepreneurs.

Although the International Entrepreneur Rule was published three days before the end of Obama Administration and was originally scheduled to go into effect in July 2017, its implementation was delayed twice, finally going into effect in December 2017. Now, DHS is trying to eliminate the rule entirely.

Declining start-up rate and aging firms

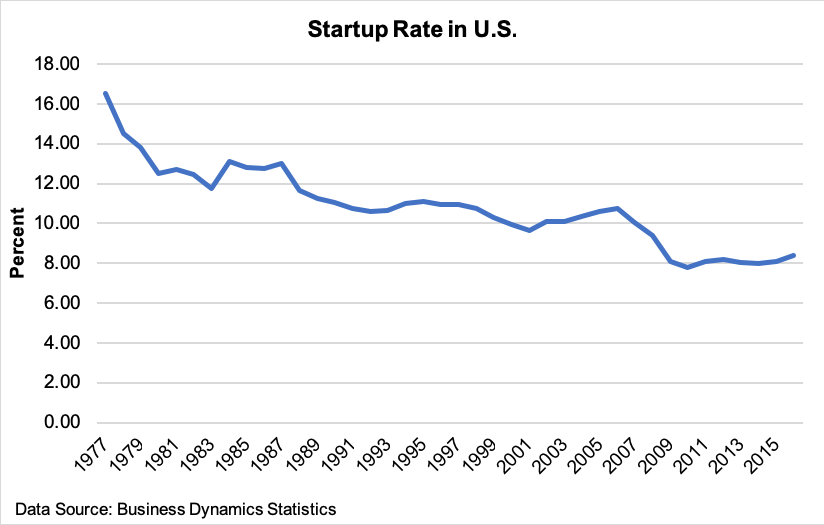

The figure below shows the proportion of newly created employer firms (private firms in the nonagricultural sector with one or more employees) to the total number of employer firms. The startup rate is declining; in 2016, the latest data point, the startup rate of 8.39 % is nearly as half what it was in 1977, 16.53%.

The rate stays relatively flat during the 1990s and early 2000s, around 10–11%; the subsequent dramatic plunge occurred during the Great Recession. Although the startup rate has made a slight recovery from its lowest point of 7.78% in 2010, the pace is slow, and it is far from the pre-Recession level.

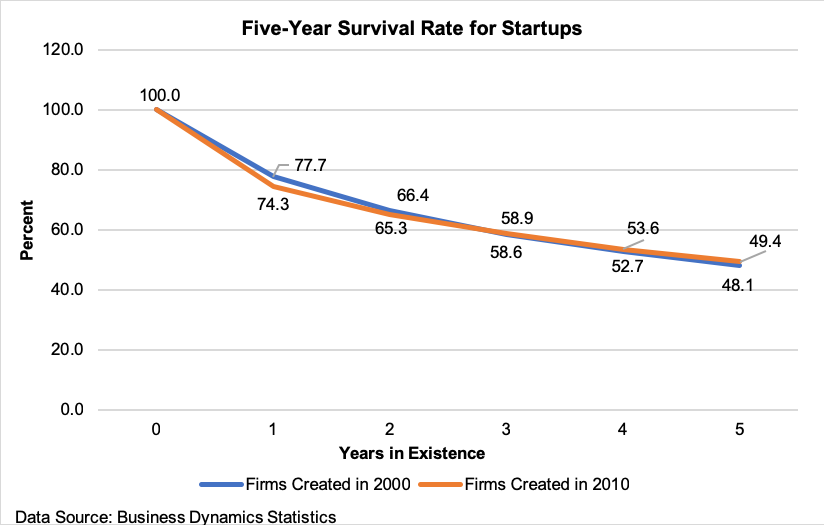

While job growth and the unemployment rate have returned to their pre-Recession levels, something may be discouraging people from starting their own businesses. Has it become harder for new businesses to survive? We compare the five-year survival rates for companies created before and after the recession.

The figure above shows the survival rate for firms created in 2000 and firms created in 2010. The percentage of those that went out of business within a year increased by 15%, from 22.3% in 2000 to 25.7% in 2010. The higher failure rate persists in the second year; reaches nearly the same level in the third year; and then remains slightly higher for firms started in 2010. After a new business survives its first three years, those created in 2010 have a somewhat greater chance of survival than those created in 2000. However, fewer new businesses are being created.

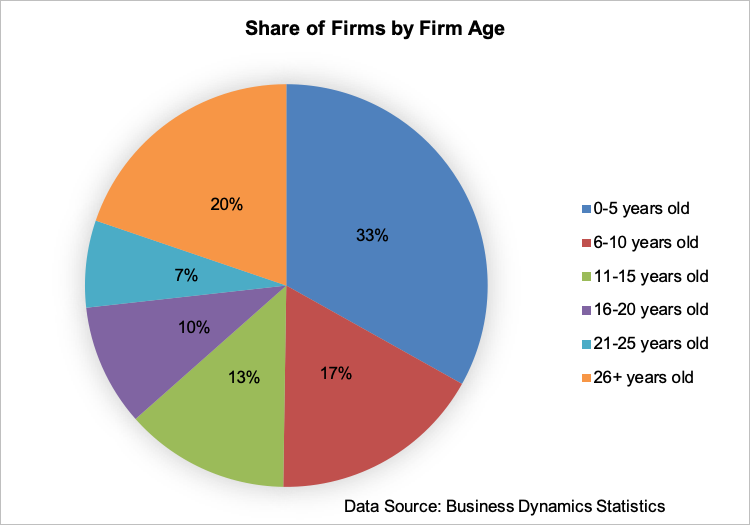

The next step is to examine current business formation by firm age. The figure below shows the percentage of firms by age in 2016.

Approximately one-third of employer firms in the United States are young firms, in business for five years or less, while 20% have been in business for more than 25 years. Half the firms are 10 years old or younger. It appears the United States is full of young and middle-aged firms. However, comparing the number of establishments reveals a different picture, where an establishment is defined as a stand-alone operation that may or may not be part of a firm.

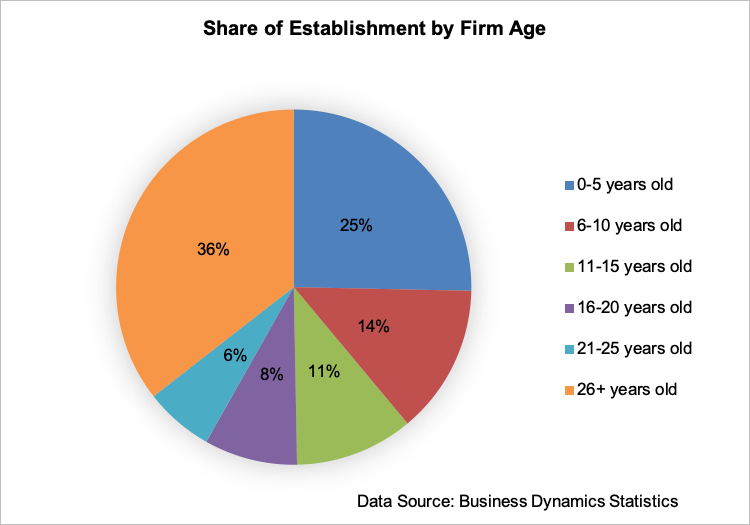

The figure above, illustrating the share of establishments by firm age, shows 36% of establishments belong to firms that have existed for more than 25 years. Although one-third of firms are young firms, only one-quarter of establishments in the United States are less than six years old.

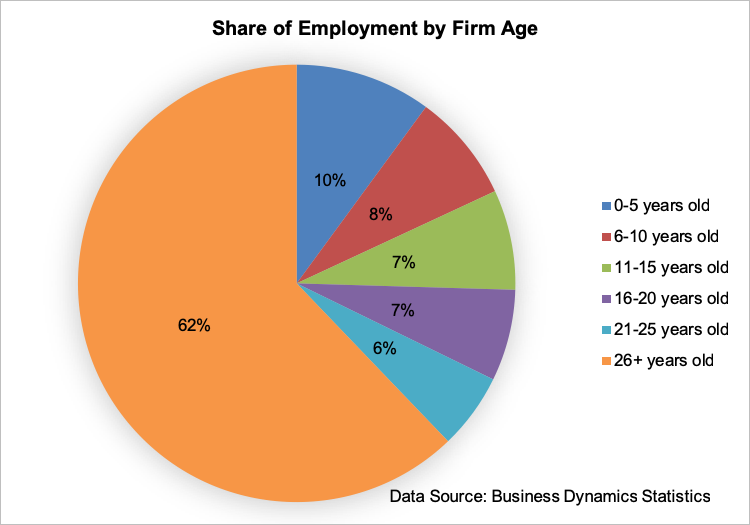

Meanwhile, the graph below, depicting the share of employment by firm age in 2016, indicates 62% of employment comes from old firms, but only 10% from young firms. Old firms are creating new establishments and expanding their size.

Immigrant Entrepreneurship Trend

Startups not only create employment and increase innovation; they also exert competitive pressure on old and large firms. Yet fewer startups are being generated, and the U.S. government has been seeking a way to encourage the launching of a new business. While native-born Americans are less likely to become entrepreneurs, immigrants play a key role in entrepreneurship.

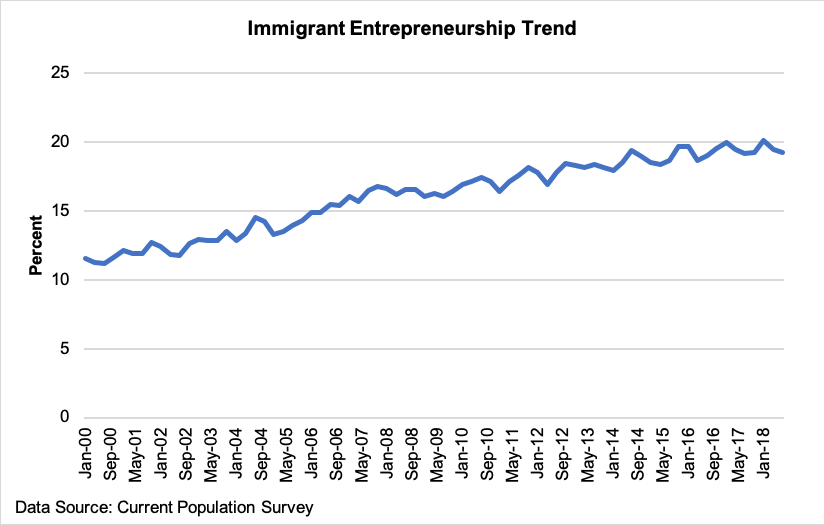

In the United States, the percentage of immigrant entrepreneurs has been growing since 2000. The figure above shows the proportion of foreign-born business owners (including both incorporated and unincorporated business owners) to all business owners. In 2000, approximately 11.5% of entrepreneurs were foreign-born, but by the beginning of 2018, that share had reached 20% (although it then trailed off slightly).

The rising percentage of immigrant entrepreneurs in the United States is not only due to the increase in the proportion of foreign-born individuals in the labor force, but also because fewer native-born persons become entrepreneurs. The figure below compares entrepreneurship rates for native- and foreign-born workers.

The orange line represents the proportion of foreign-born entrepreneurs in the foreign-born labor force, and the blue the proportion of native-born entrepreneurs in the native-born labor force. While the foreign-born entrepreneurship rate increased through 2007 and has remained relatively flat since then, the native-born entrepreneurship rate has been declining since 2006. The entrepreneurship rate has been higher for foreign-born individuals since 2006.

Many countries, including Canada, Singapore, and the United Kingdom, seek to increase employment and innovation by attracting high-skilled foreign entrepreneurs through the use of a “startup visa.” The United States is one of the few leading economies that do not have such a visa category. As a result, foreign entrepreneurs seeking to start their business in the country enter on another type of visa, such as the H1-B, and endure a complicated process to start their own business.

The International Entrepreneur Rule was considered a huge step toward implementing a startup visa. Its stringent initial requirements, such as requiring the immigrant receives “significant investment of capital (at least $250,000) from certain qualified U.S. investors with established records of successful investments in the 18 months before applying,” indicate a temporary stay would only be granted to business owners with exceptional promise who are likely to bring employment to the United States in the future. However, the U.S. government is moving to eliminate the International Entrepreneurship Rule. As fewer startups are being born and native-born people are less willing to become entrepreneurs, the United States will need to devise another solution if it wishes to compete on the global stage.