Paul Krugman

February 08, 2018

Late last year Republicans enacted a huge tax cut, mainly for corporations. They then seized on some seemingly supportive data points – investment announcements by some major corporations, bonuses paid to some employees, an uptick in some measures of wage growth – as evidence that the cut was already benefiting workers. But while there is a case for cutting corporate taxes, the logic of that case says that any benefits to workers should unfold gradually over time, not show up in a few weeks.

And there is also a case against corporate tax cuts, even aside from the fact that revenue must be raised somewhere, and getting less from profit taxes means either raising other taxes or cutting spending.

The purpose of this note is to lay out a stylized framework for thinking about these issues. There exist carefully specified general-equilibrium models for tax incidence, but my sense is that there’s not enough intuition in these models for them to play as large a role in the discussion as they should. So, I’m going to present a slightly different approach, one that I described in a somewhat disconnected series of blog posts over the course of the tax debate. Here I try to collect it into a unified, comprehensible narrative.

1. The simple analytics of trickle-down

Imagine that we had a one-sector economy with no monopoly power, open to inflows of foreign capital. In reality, the economy is characterized by considerable monopoly rents, most of the capital stock isn’t in the corporate sector, and most of GDP is nontradable. These complications all weaken the extent to which corporate tax cuts trickle down to wages. But let’s give some hostages here, and consider the most favorable case.

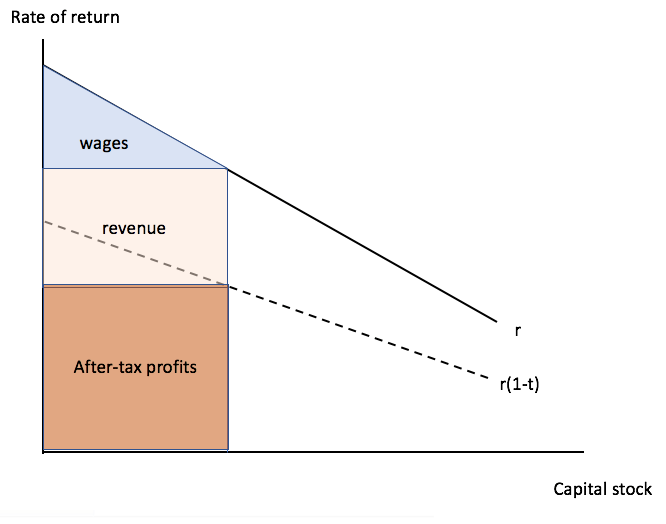

Such a stylized economy would look like Figure 1. The downward-sloping line is the marginal product of capital, which is equal (in this model) to the pre-tax rate of return r. The after-tax return is r(1-t), where t is the tax rate. Given an initial capital stock K, GDP is the integral of the area under the r curve up to K. Of this, rK goes to pre-tax profits, of which the government takes a share t and the rest goes to after-tax profits. What’s left, the triangle at the top, is wages.

Now, the key justification being offered for corporate tax cuts is that the U.S. is the international mobility of capital: reducing U.S. taxes will, supposedly, draw in investment from abroad, either from U.S. corporations bringing money home or foreign corporations buying into the U.S. economy. We can capture this effect by adding a supply curve for capital, as in Figure 2.

For a small open economy, this supply curve would be horizontal in the long run. It is, however, surely upward-sloping for the United States.

Now suppose the corporate tax rate is cut to a lower level t’. This raises the after-tax rate of return for any given capital stock. Over time the capital stock rises to K’. This in turn leads to higher wages.

Figure 2

The crucial words, however, are “over time.” For a variety of reasons, it would take a number of years for the capital stock to rise to its long-run level.

What are these reasons? One is that adjusting the capital stock would take time even if purely domestic factors were involved: a large increase in capital formation would drive up the wages of construction workers, the rent on construction equipment, the prices of commodities used in construction, etc. This is why we don’t expect Tobin’s q to be one all the time.

Beyond this, we’re talking about capital inflows here, which would have to have as their counterpart an expanded trade deficit, effected via a temporarily strong dollar. And this temporary strength of the dollar would in itself be a deterrent to capital inflows, since investors would expect it to go back down again.

The bottom line is that the short-run supply curve of capital should be more or less vertical; full trickle-down should happen only in the long run, where this run is measured in a number of years. Whatever cherry-picked good news comes in the first few weeks after a corporate tax cut is, almost by definition, irrelevant to the case for that cut.

2. Long-run welfare effects

Since the capital stock is effectively fixed in the short run, the short-run incidence and welfare effects of a corporate tax cut are simple: no change in real income, all the gains go to owners of capital. In the long run, however, the capital stock does rise. So, what are the effects?

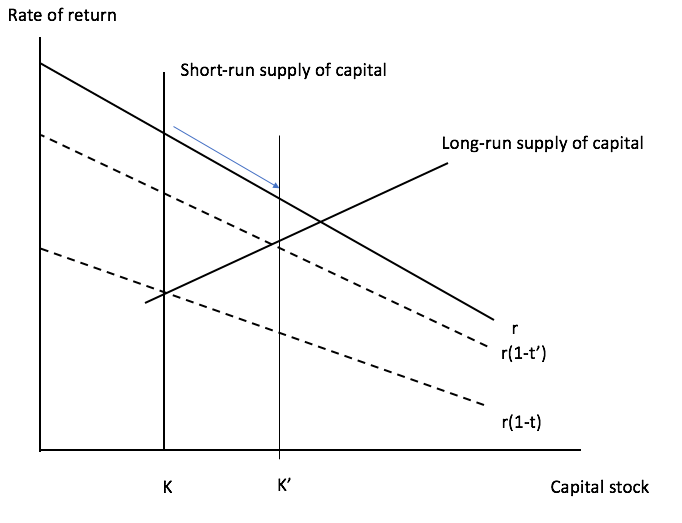

Again, as a starting point we can think of a downward-sloping demand for capital, reflecting its marginal product. We can also think of an upward-sloping supply of capital, with the upward slope reflecting both the size of the US — we’re probably around half of the world’s capital market not subject to capital controls — and the imperfect nature of capital mobility, even now.

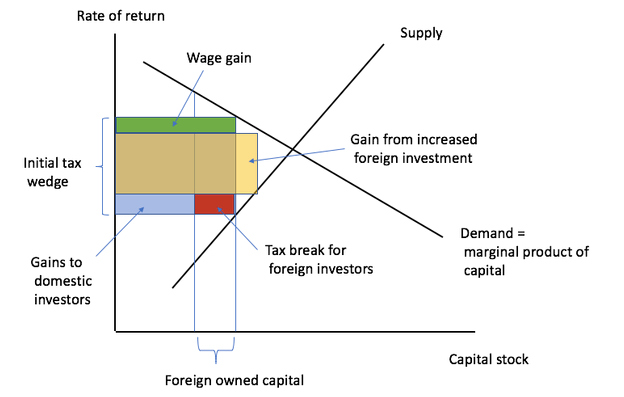

For current purposes it’s helpful to focus not on the corporate tax rate per se but rather on the wedge corporate taxes place between the rate of return to capital before taxes — which is assumed equal to its marginal product — and the after-tax return received by investors. This does not mean changing the model, it’s just a way of presenting the picture that bypasses some messy algebra that can (and has) led some economists to make errors. So, we think of the corporate profits tax as being kind of like an excise tax on capital, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Notice that I’ve indicated here the reality that a significant fraction of the current capital stock is owned by foreigners. This is a big deal: gross U.S. liabilities to the rest of the world are around 1.7 times GDP, and around 35 percent of corporate equity is foreign-owned. As we’ll see in a minute, it matters for the welfare analysis.

What happens if we cut corporate taxes? We reduce the size of the corporate tax wedge, which brings in more capital from abroad and raises GDP. But it doesn’t raise GNP – the income of domestic residents – by the same amount, for two reasons. First, the additional capital doesn’t come free: we have to pay foreigners for the use of the additional capital (or get less income from investments abroad if it’s U.S. capital coming home.) Second, we pay a higher rate of return on the foreign capital already here. So net international investment income falls, offsetting at least part of the rise in GDP. In fact, the fall in investment income could be larger than the rise in output, so that national income actually falls.

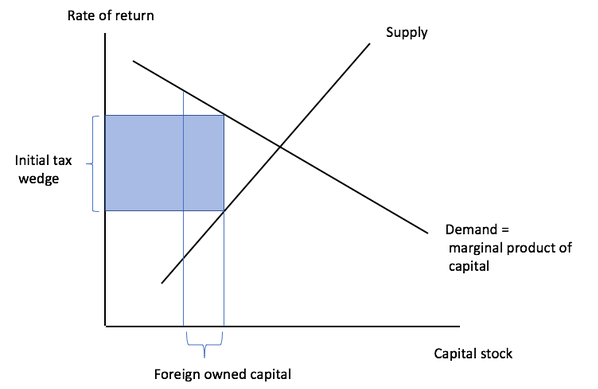

Figure 4 tells the slightly intricate story, for a small change in the tax rate (so we can ignore triangles):

Figure 4

The lower tax rate shrinks the wedge, leading to a higher capital stock, lower pre-tax rate of return, and higher wages. The green rectangle at the top is the part of the tax cut that’s passed through to increased wages. As long as the supply curve for capital is upward-sloping, it also leads to higher after-tax returns to capital, with the gains partly accruing to domestic investors, partly to foreign investors. These gains are offset by a loss of revenue.

The possibility of overall gains to the U.S. economy comes from the fact that we started with a wedge: the rate of return on investment, equal to the pre-tax return on capital, was larger than the cost of capital from abroad, equal to the after-tax return. So, bringing in more capital produces a net gain equal to the change in the capital stock times that wedge – the yellow rectangle at the right.

Notice, however, that this is a lot smaller than the rise in GDP, which is the whole pre-tax return times the rise in the capital stock. Since the initial tax rate was 35%, the gain to the U.S. should be only 0.35 times whatever gain we get in GDP.

And that’s without taking into account the extra payments to foreign capital already here – the red rectangle at the lower right. Back of the envelope calculations suggest that once we take that into account, any net gains are very small, and maybe negative.

One way to think about all this is that because the U.S. is a big player in world capital markets, and already effectively employs a lot of foreign capital, we effectively have considerable monopsony power in world capital markets. When we cut corporate taxes, we end up attracting more foreign capital but paying the capital we already employ more. This analysis shows that it is not at all clear that the cut in corporate tax rates works in our favor, which makes the case for the tax bill just enacted look remarkably weak.