Paul Krugman

December 08, 2018

Ben Bernanke wrote a paper arguing that the financial crisis and the resulting credit crunch were central to the Great Recession. His summary measures of financial conditions fall into two categories: Panic Factors (related to the financial panic) and Balance Sheet Factors (related to borrower and lender balance sheets). Using time series analysis, he estimates their impact on output and concludes that Panic Factors simulate the fluctuations in economic growth substantially better than the Balance Sheet Factors.

I wrote a piece raising questions about that verdict. I have trouble seeing the “transmission mechanism” — the way in which the financial shock is supposed to have affected actual spending to the extent necessary to justify a finance-first account of the slump. Dean Baker, who has long argued that the burst housing bubble was the main factor in both the slump and the slow recovery, with financial disruption a minor and transitory factor — a view I mostly agree with— has weighed in.

What Bernanke does in his paper, as I see it, is a kind of reduced-form analysis, identifying factors in the credit markets and using time series to estimate their impact on output. What Baker does, and I largely follow, is more of an accounting-based structural analysis: look at the components of aggregate demand, and ask what their behavior seems to imply about causes. In principle, these approaches should be consistent.

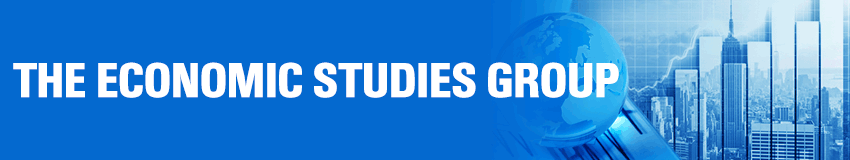

Here I summarize these views because it still seems to me that we’re somewhat talking past each other. The starting point for both of us thinking about the Great Recession and aftermath is that we clearly had a very large housing bubble. Here’s the ratio of housing prices to owner’s equivalent rent, the sort of housing equivalent of the P/E ratio for stocks:

Figure 1: S&P/Case-Shiller 20-City Composite Home Price Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Housing prices went extremely high relative to rental rates in 2006 (and consumer prices more generally), then suffered a long and protracted fall. This decline started well before the period of severe financial distress, which was a fairly short episode from September 2008 to around June 2009. And prices were still way down years later, which suggests that while the credit crisis surely accelerated the pace of decline, prices were going to come down and stay down regardless of what happened to the financial system.

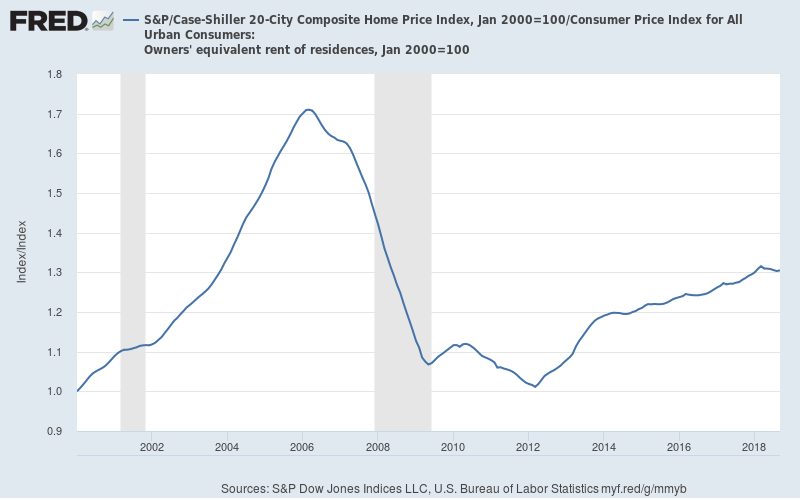

Given a housing price slump of this magnitude, you had to expect large macroeconomic impacts. Consider investment, which is what you’d expect a credit crunch to depress. The bust led to a huge decline in residential investment, directly subtracting around 4 percentage points from GDP.

Figure 2 Fixed Residential Investment as a Share of Gross Domestic Product

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

So, can we attribute this decline to credit conditions? If so, why did residential investment remain depressed five years after credit markets normalized?

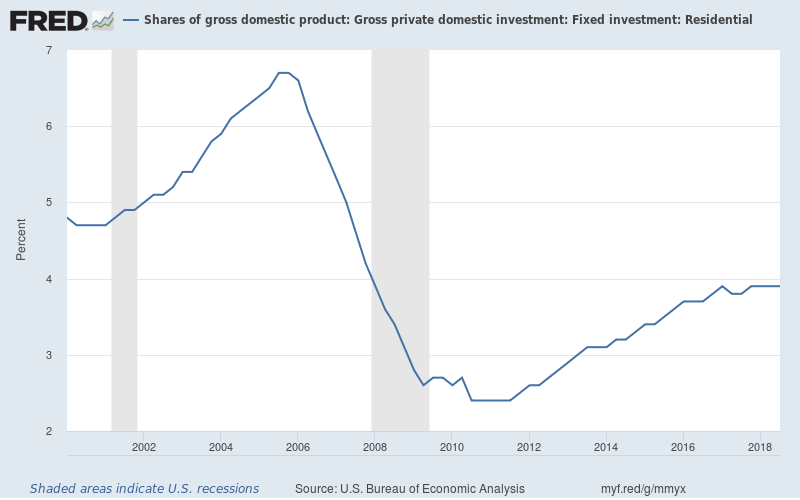

The bust was also linked to a fall in consumer spending because of the wealth effect, and a decline in nonresidential, i.e., business investment, because of the slump in demand brought on by the first two effects.

Figure 3 Fixed Nonresidential Investment as a Share of Gross Domestic Product (left)

and Real Gross Domestic Product (right)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

But this decline was only about the same size as the decline in the early 2000s slump — which, admittedly, was partly because of the collapse in telecom spending, but still. And it seems pretty easy to explain simply by the accelerator effect: business investment always plunges when the economy is shrinking, which it was doing mainly because of the housing bust.

So, when I look at these two key drivers of the Great Recession and subsequent depressed period, I don’t see an obvious role for financial disruption. Bernanke’s VARs tell a different story; but I generally don’t trust VARs unless I can relate them to phenomena we see from other perspectives. Something very much like the Great Recession seems like an inevitable consequence of the bursting of the housing bubble. And the magnitude of the shocks — around 4 percent of GDP for housing investment, perhaps around 2 percent for the wealth effects of the decline in home equity — looks well within the range needed to explain the whole thing.

My problem with Bernanke’s paper is that I have trouble seeing the “transmission mechanism” — the way in which the financial shock is supposed to have affected actual spending to the extent necessary to justify a finance-first account of the slump. The paper is mainly focused on the first year or so after Lehman, while both Baker and I are more focused on the multiyear depressed economy that lasted long after the financial disruption ended. (Bernanke’s measures show the same spike and fast recovery as other stress indexes.) But there’s still a clear difference.

Bernanke has replied to those questions: Looking at the GDP components he says that despite the deterioration in residential investment real output growth was positive until 2008q1 and declined little early 2008. The panic accelerated the downturn in the fall of 2008 while residential investment continued to fall. The recovery began once the panic subsided in the spring of 2009. What Bernanke offers is, as I read it, mainly evidence that the pace of decline accelerated a lot during 2008-2009. Indeed, it did — and no reasonable person would deny that the combination of financial disruption and sheer fear that gripped the world after September 2008 brought the slump forward and made the decline steeper than it would otherwise have been.

But did it make the decline deeper as well as steeper? The unemployment rate averaged 9.6 percent in 2010 and 8.9 percent in 2011. How much did the financial crisis contribute to these extremely high levels of economic slack, long after the disruption had ended? I still don’t see how to make it the main story.

Now, does this mean that rescuing the financial system was pointless? Here Dean Baker and I disagree, I think. Dean says yes, because finance didn’t cause the slump. I think that the slump we had didn’t have much to do with finance — but the slump we would have had if the financial system had been allowed to implode might have been much worse. On precautionary grounds, bailouts were in my view the right thing to do, although the terms were too sweet for the bankers.

On the other hand, the fact that we suffered such a deep, prolonged slump despite rescuing banks shows the limits of a finance-centered view.